Gnostic Lafferty

- Jon Nelson

- Oct 13, 2025

- 17 min read

Lafferty drew on ideas from Gnosticism for many of his most important short stories, from "Snuffles" to "The All At-Once Man" to "In the Turpenine Trees": The gaps in historians' knowledge about Gnosticism were grist for his metaphysical imagination throughout his writing career. I’d like to have a post on this blog where I can keep updating my understanding of this side of Lafferty’s work. That’s the purpose of this space. It will include a timeline of how the West has understood the Gnostic tradition. I will add updates over time, along with a running list of Lafferty stories where Gnosticism plays a significant thematic role. This will be my hub post for Gnostic Lafferty.

Ancient Era (1st–4th Centuries)

Late 1st–2nd Century:

Origins and Early Gnostic Sects. Gnostic ideas coalesced in the late first and early second centuries, likely around cosmopolitan centers like Alexandria. Diverse sects emerged, e.g. the Basilideans and Valentinians, emphasizing personal mystical knowledge (gnosis) and mythic cosmologies that distinguished a remote supreme God from an ignorant creator (the Demiurge). These groups saw themselves as Christian, offering esoteric teachings about Jesus and salvation through hidden knowledge. Their worldview was typically dualistic: the material world is flawed or evil, and salvation comes by awakening the divine spark within through revealed knowledge. Gnostic teachers like Valentinus (active c. 150 CE) even operated within the early church, though proposing unorthodox cosmologies. The movement’s exact origins remain debated. Scholars have traced influences to heterodox Jewish mysticism, Middle Platonic philosophy, and Persian dualism.

2nd Century: Orthodox Reaction

“Heresy” Identified. By the mid-2nd century, Gnostic Christians were significant enough that emerging orthodox leaders reacted. In 180 CE, Bishop Irenaeus of Lyon penned Against Heresies, a massive refutation of what he called “knowledge falsely so-called,” targeting Gnostic doctrines. Irenaeus catalogued Gnostic systems (Valentinian, Sethian, etc.), preserving their myths second-hand while condemning them as heretical distortions of apostolic teaching. Other early heresiologists (Hippolytus of Rome, Tertullian of Carthage, and Epiphanius) wrote polemics portraying Gnostics as dangerous sectarians. These Church Fathers uniformly interpreted Gnosticism as a deviation from Christianity, emphasizing its rejection of the material world and the Hebrew Creator. By identifying Gnostics as heretics, orthodox authorities justified restricting the transmission of Gnostic documents; indeed, few original Gnostic writings survived the concerted effort to destroy them in antiquity. What little was known of Gnostic theology for centuries came only through the hostile (and often biased) summaries in these patristic sources.

3rd Century: Gnosis in New Guises. Even as many 2nd-century Gnostic groups waned, new religious movements carried forward esoteric and dualist tendencies. In the mid-3rd century (c.240 CE), the prophet Mani in Persia founded Manichaeism, a syncretic faith drawing on Christian, Gnostic, and Zoroastrian ideas. Mani’s religion taught a cosmic dualism of Light and Darkness and the salvation of the soul from matter, themes similar to earlier Gnostic cosmology. Manichaeism spread widely (from the Roman Empire to China), and later observers called it a form of “Persian Gnosticism.” Around the same time in Alexandria, Christian theologians like Origen grappled with Gnostic ideas: Origen’s theology addressed concepts of pre-existent souls and allegorical scripture interpretation, partly in debate with Gnostic thought. In the pagan philosophical sphere, Plotinus (founder of Neoplatonism) took notice of Gnostic metaphysics, In the Enneads (c.270 CE), he critiques unnamed Gnostics for denigrating the material cosmos. This unique instance of a non-Christian rebuttal shows that Gnostic cosmology had permeated intellectual circles enough to provoke a philosophical controversy. Plotinus and his circle attacked the Gnostics’ pessimism about creation, defending the beauty of the world against the Gnostic notion of an ignorant creator.

4th Century: Decline and Marginalization.

By the late 3rd and 4th centuries, Gnostic sects in the Roman Empire dwindled under external pressures. The ascendant orthodox Church, now backed by Imperial authority (after Constantine), intensified efforts to root out heresy. In 325 CE the Council of Nicea defined orthodoxy in a way that implicitly excluded Gnostic Christologies. Gnostic and dualist communities either went underground or were stamped out; by the end of the 4th century, organized Gnostic churches in the Greco-Roman world had largely disappeared. An important example is Manichaeism: condemned by Imperial edicts, its followers were persecuted within Roman territories. (Notably, Augustine of Hippo (later a Church Father) spent his youth as a Manichaean hearer before converting to orthodox Christianity; he later wrote extensively against Manichaean doctrines, further solidifying the heretical reputation of Gnostic-style beliefs.) By suppressing these movements, orthodox Christianity successfully made Gnosticism a short-lived, misguided offshoot of the true faith. But a few embodied reminders of ancient Gnosis persisted beyond the Empire: the Mandaeans of Mesopotamia, for example, continued practicing baptismal, dualistic religion (with roots in Judeo-Gnostic tradition) into late antiquity and beyond. In general, however, by 400 CE the primary era of Gnosticism had ended, surviving mainly in distant lands or in scattered texts hidden away, awaiting future discovery.

Medieval Era (5th–15th Centuries)

Survival on the Margins:

After antiquity, classic Gnostic cosmologies largely vanished from the mainstream, but related currents survived at the fringes of the Christian and Near Eastern world. Eastern dualist sects kept Gnostic-style ideas alive. Manichaeism endured for centuries in the East: Manichean communities persisted in Central Asia (a Manichean Uighur kingdom flourished in the 8th–9th c.) and even in China before dying out in the late Middle Ages. In the Mesopotamian wetlands, the Mandaean religion (often seen as a Gnostic offshoot of early Christianity or Judaism) quietly continued its rituals of light versus darkness; remarkably, the Mandaeans survive to this day as a small Gnostic-style sect practicing rituals of purification. Within the Byzantine Empire and its borderlands, new heresies with “Gnostic” traits appeared: for example, the Paulicians (Armenia, 7th–9th c.) and later the Bogomils (Bulgaria, 10th c.) preached a form of Christian dualism reminiscent of Manichaeism. These groups taught that the material world was the devil’s creation or that two gods (one good, one evil) ruled the universe. ideas echoing earlier Gnostic doctrines of an evil world-creator. Such sects often used parts of the New Testament but rejected the orthodox church hierarchy, which led the Byzantine state and Orthodox Church to brand them heretics. Medieval Byzantine sources recount debates and imperial persecutions against the Paulicians and Bogomils; the Bogomil leader Priest Bogomil was denounced and perhaps burned as a heretic by Emperor Alexios I. This shows Gnostic-like dualism remained a theological issue for Christians well into the Middle Ages.

12th–13th Century: “Gnosis” in Western Heresies.

Gnostic thought had a notable resurgence in high-medieval Western Europe with the rise of the Cathars (also called Albigensians) in the 12th–13th centuries. The Cathars, centered in southern France, embraced a stark dualist theology: an evil god (Satan) created the material world, whereas a good God ruled the spiritual realm. a cosmology similar to ancient Gnostic and Manichaean teachings. Scholars believe Catharism was influenced by the older Bogomil dualism coming from the East. Cathars claimed to preserve a “pure” apostolic Christianity, but their rejection of the material sacraments and the Church’s authority led Rome to condemn them. The Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229) was launched by the papacy to exterminate this “Gnostic” heresy; the crusade and subsequent Inquisition destroyed the Cathar movement. Some contemporaries referred to Cathars and other dualists as “Manichees,” explicitly linking them to the ancient Gnostic-Manichaean tradition. Thus, during the Middle Ages the idea of Gnosticism survived chiefly as a label for heresy, applied to any radical dualist sect that arose. Orthodox theologians of both the Eastern and Western churches continued to use the memory of Gnostic/Manichaean heresy as a cautionary tale and an object of refutation. In the medieval Jewish world, elements of Gnostic cosmology found their way into Kabbalistic mysticism (e.g. themes of divine emanations and cosmic repair), though direct influence is debated. Likewise, certain strains of Islamic esotericism (such as Ismaili cosmologies) mirrored Gnostic dualism and emanation theories. These parallels suggest that the intuitive appeal of Gnostic ideas, a hidden truth about divine light trapped in darkness. transcended cultural boundaries, even as the formal Gnostic sects of antiquity had long since vanished.

Late Middle Ages:

By the 14th–15th centuries, open dualist movements in Europe had been crushed, and the Renaissance was dawning with a renewed interest in pre-Christian antiquity. Knowledge of the original ancient Gnostics at this time was extremely limited; it survived only in the preserved writings of the Church Fathers. Intellectuals and clergy who studied those patristic texts were aware of figures like Valentinus, Basilides, and Marcion as ancient heretics with esoteric doctrines, but no primary Gnostic writings were available to give their own perspective. Gnosticism’s historical reputation by 1500 was uniformly negative in orthodox circles. The name connoted deceptive heresy. Yet the Renaissance’s fascination with Hermetic and Neoplatonic writings (e.g. the Corpus Hermeticum discovered in 1460) showed a broader curiosity about mystical knowledge from antiquity, a climate that would soon also rekindle interest in Gnostic ideas when the time was ripe.

Enlightenment Era (17th–18th Centuries)

Reintroducing the Term “Gnosticism”:

During the Reformation and Baroque period, the term “gnostic” re-entered discourse. initially as a polemical insult. Scholars and theologians of the 16th–17th centuries drew parallels between their opponents and ancient Gnostics: for example, Erasmus of Rotterdam in the 16th century and later Protestant polemicists accused various Catholic thinkers of being “gnostics,” and vice-versa. The word came to signify someone claiming elitist spiritual knowledge or deviating from accepted doctrine. In this context, Henry More (1614–1687), an English theologian and philosopher, made a pivotal contribution: he coined the actual term “Gnosticism.” In his 1669 commentary on Revelation, More used the neologism “Gnosticisme” to describe the heretical sect at Thyatira mentioned in the New Testament. This appears to be the first systematic use of “Gnosticism” (-ism) as a category encompassing the ancient heresies of the early church. Thus, by the late 17th century, Gnosticism was identified in scholarly language as a distinct historical phenomenon, essentially, an umbrella term for a whole range of early heterodox sects focused on secret gnosis.

18th-Century Scholarship – First Histories of Gnosticism:

The Enlightenment brought a more analytical (and sometimes sympathetic) approach to the study of heresy. Church history scholars began the first modern attempts to chronicle Gnostic movements in a less polemical manner. Notably, the German historian Johann Lorenz von Mosheim (1694–1755) included the Gnostics in his influential ecclesiastical histories. Mosheim proposed that Gnosticism might have developed independently in the East (in Greece and Mesopotamia) before blending with Jewish and Christian elements, rather than being simply a Christian deviation. Enlightenment thinkers, with their emphasis on reason and anti-authoritarianism, sometimes reinterpreted the ancient Gnostics in a positive light. A few intellectuals began to admire Gnostics as early freethinkers. For instance, some writers portrayed Gnostics as enlightened mystics who valued inner experience over external dogma, drawing a parallel between Gnostic insistence on personal knowledge and the Enlightenment’s valorization of reason and individual insight. Historian Gottfried Arnold (1666–1714) exemplified this trend: in his Impartial History of the Church and Heretics (1699), Arnold controversially praised various heretics (including Gnostics) for preserving true spirituality oppressed by the institutional church. By the late 18th century, “Gnosticism” was established as a subject of inquiry in its own right. French scholar Jacques Matter carried this further in the early 19th century (1828) with the first full-length Histoire critique du Gnosticisme, but the groundwork was laid in the Enlightenment era’s willingness to catalog and reassess all historical beliefs. This period expanded the geographical perspective on Gnosticism: scholars began to speculate that Gnostic ideas might owe much to “Eastern” (Persian or oriental) sources, not just Greek philosophy. For example, early theories by J. Horn and E. F. F. Ledrain (later 18th–early 19th c.) suggested Persian (Zoroastrian) origins for Gnostic dualism. Meanwhile, esotericists and Romantic-era mystics at the turn of the 19th century (late Enlightenment into Romanticism) adopted the term “gnosis” in a more mystical sense. By the Romantic period (circa 1800), “gnosis” was sometimes used to signify an inner, emotional spiritual insight, a state of mystical awareness that the Romantics found intriguing. In short, the Enlightenment and its aftermath not only systematized the historical study of Gnosticism but also subtly transformed its image: from a reviled heresy to, in some circles, an almost noble quest for truth against dogmatic tyranny.

Modern Era (19th – Early 20th Centuries)

19th-Century Theories and Discoveries:

The 19th century saw major developments in understanding Gnosticism, fueled by both theoretical frameworks and new textual evidence. Scholarly opinion split over Gnosticism’s origins and nature. The influential History of Religions approach (Religionsgeschichtliche Schule) argued that Gnosticism was essentially a pre-Christian phenomenon – a syncretistic religion that only later intersected with Christianity. For instance, scholars like Wilhelm Bousset (1865–1920) and Richard Reitzenstein (1861–1931) posited that Gnosticism drew from ancient Iranian, Mesopotamian, and other oriental cosmologies, which then infiltrated early Christianity. They emphasized themes like the cosmic battle of light and dark as evidence of Persian influence in Gnostic dualism. On the other hand, prominent church historian Adolf von Harnack offered a contrasting interpretation: he saw Gnosticism as an internal evolution of Christianity under the influence of Greek philosophy. Harnack famously dubbed Gnosticism “the acute Hellenization of Christianity,” implying it was an extreme, premature mingling of the Gospel with Platonic and philosophical concepts. In Harnack’s view, Gnosticism sprouted within the church itself (in the 2nd century) as a kind of premature theology, rather than being an import from Persia. These debates marked the first major scholarly controversy over Gnosticism: Was it essentially an exotic foreign import that corrupted Christianity, or a native Christian heresy sparked by overzealous intellectualism? Even as scholars debated, archaeological discoveries were beginning to provide new data. For over 1,500 years, nearly all knowledge of Gnostic literature came second-hand. But in the late 18th and 19th centuries, a few precious Gnostic manuscripts resurfaced:

In 1769, the Scottish explorer James Bruce acquired a Coptic codex (now called the Bruce Codex) in Upper Egypt, which contained mysterious texts like the Books of Jeu. This was one of the first direct glimpses of original Gnostic writings in modern times.

Around the same time, the Askew Codex (purchased by physician Anthony Askew) came to light. a Coptic manuscript eventually obtained by the British Museum in 1785. It contained Pistis Sophia, a lengthy Gnostic dialogue. For the 19th-century scholars, Pistis Sophia became a key work for understanding Gnostic cosmology and ritual (it was translated into Latin in 1851, providing the scholarly world a rare firsthand Gnostic scripture).

In 1896, the Berlin Codex (Papyrus Berolinensis 8502) was purchased in Cairo. This 5th-century Coptic manuscript included the Gospel of Mary, the Apocryphon of John, and other texts. It offered direct evidence of Sethian and Valentinian lore. Though published only in the early 20th century, its discovery in 1896 signaled that more “lost” Gospels might still be found.

Additionally, scholars in the late 19th century discovered fragments of Gnostic gospels in the original languages; for example, Greek fragments of the Gospel of Thomas were unearthed at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt (1897–1903), though at the time they were not fully identified as Thomas’s gospel.

These finds, though limited, energized academic Gnostic studies. For the first time, researchers could read some Gnostic teachings in their own words, not just through hostile patristic quotations. It became clear that Gnostic literature was rich and complex. By 1900, a few critical editions of Gnostic texts (like Pistis Sophia) had been printed, and scholars such as G. R. S. Mead compiled translations and commentary (Fragments of a Faith Forgotten, 1900) to make this arcane material more accessible.

Early 20th Century – Gnosticism as a “Religion”:

In the early 20th century, scholars began synthesizing the available evidence into overarching interpretations of Gnosticism. A landmark figure was Hans Jonas (1903–1993). In the 1920s–30s, Jonas studied Gnostic texts (his 1934 dissertation was on Gnosticism), and after World War II he published The Gnostic Religion (1952). Jonas’s work was groundbreaking in that he treated ancient Gnosticism as a coherent religious worldview in its own right, not merely a Christian heresy. He analyzed the existential angst in Gnostic myth – the alienation of the soul in an evil cosmos – through the lens of modern existential philosophy (in dialogue with Heidegger). Jonas highlighted the radical dualism between the true God and the material world as the essence of Gnostic thought. His approach was phenomenological and philosophical, emphasizing how Gnosticism answered deep human feelings of alienation (geworfenheit, being “thrown” into a hostile world). Jonas effectively “rewrote” Gnosticism as an ancient religion of salvation, comparable to other religions, rather than a deviant sidebar of Christianity. This had a lasting impact: subsequent generations often spoke of the Gnostic religion or Gnostic tradition as a distinct phenomenon encompassing certain myths and doctrines. Around the same time, other scholars like Walter Bauer (who in 1934 proposed that so-called heresies like Gnosticism might represent original forms of Christianity in some regions) were challenging the orthodox-centric view of early Christian history.

Meanwhile, interest in Gnosticism was not confined to historians and theologians. Figures in psychology and esoteric studies found Gnostic ideas alluring. Carl Jung, the famed depth psychologist who influenced Lafferty, drew heavily on Gnostic symbolism. He saw in Gnostic myths profound archetypal truths about the self. In 1916 Jung privately wrote Seven Sermons to the Dead under the name of the Gnostic teacher Basilides, and in the 1950s Jung collaborated with scholars (including Gilles Quispel) to obtain and study a Coptic codex from Nag Hammadi (the Jung Codex). Jung regarded Gnosticism as a kind of early psychology of the soul’s journey, and he viewed gnosis as analogous to individuation, an inner awakening to Self. His follower Quispel went on to be a major scholar of Gnosticism, advocating that gnosis represented a third stream of Western thought (besides faith and reason) that emphasized direct inner experience.

By the eve of World War II, the academic community had mapped out the contours of Gnosticism fairly well (identifying sects, mythological themes, and historical spread) but still relied on limited sources. There was an air of mystery around Gnostic studies – a sense that many texts were lost and much remained speculative. All of this was about to change dramatically with a discovery in Egypt that would revolutionize the field.

Contemporary Era (Mid-20th Century – Present)

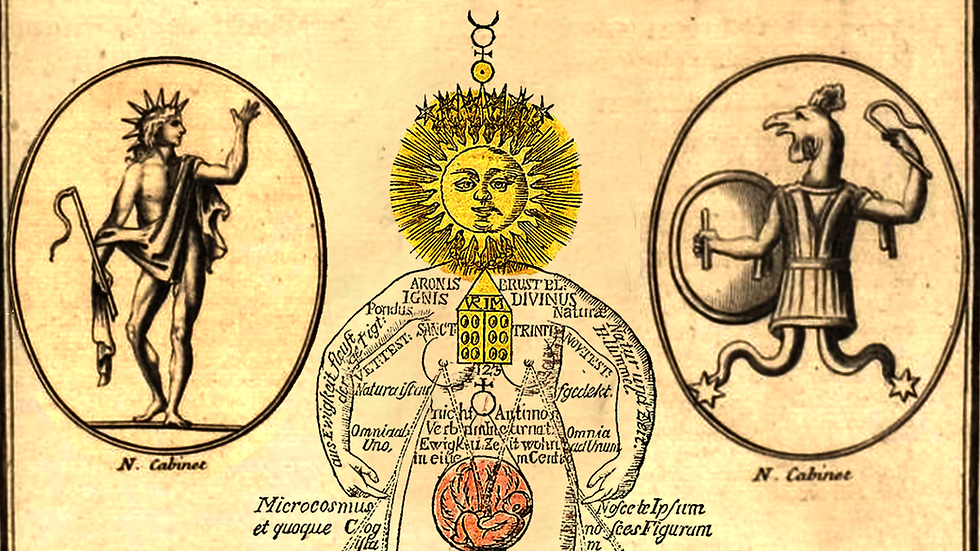

A page from Codex Tchacos (3rd–4th century C.E.), containing the Gospel of Judas. The rediscovery and publication of such ancient Gnostic manuscripts in the mid-20th and early 21st centuries profoundly expanded scholarly knowledge of Gnosticism.

1945: The Nag Hammadi Library – Revolution in Gnostic Studies.

In December 1945, a collection of twelve leather-bound codices sealed in a clay jar was accidentally discovered by farmers near Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt. This trove of Coptic manuscripts, dating to the 4th century, turned out to be a library of Gnostic writings – over fifty texts, most of which were previously unknown or known only by name. Among the texts were the Gospel of Thomas, The Secret Book of John, The Gospel of Philip, The Apocalypse of Adam, and many more works representing Sethian, Valentinian, and other Gnostic schools. The significance of the Nag Hammadi discovery is hard to overstate: before 1945, scholars knew Gnosticism mainly through the hostile filters of the Church Fathers. Suddenly, there was a wealth of primary sources (mythological gospels, mystical teachings, dialogues attributed to Jesus) offering an uncensored window into what Gnostics themselves believed. Over the next two decades, scholars (notably in France, Egypt, and the US) undertook the laborious task of conserving, transcribing, and translating these documents. By 1977, a complete English translation (The Nag Hammadi Library in English, ed. James M. Robinson) was published, making these texts widely accessible. The Nag Hammadi codices confirmed some previously reported teachings (for example, Irenaeus’s descriptions of the Apocryphon of John proved fairly accurate), but they also revealed unexpected diversity. Gnostic cosmologies were not monolithic – some texts were strongly dualistic and anti-cosmic, others (like the Valentinian Gospel of Truth) were more moderate. The early Christian landscape appeared far more varied than the traditional orthodox-versus-heretic narrative suggested. Scholars realized that what we call “Gnosticism” encompasses a broad spectrum of groups and doctrines, from radical dualists to more philosophical mystics. A poignant detail: none of the newly found writings actually called themselves “Gnostic”; the ancient authors saw their beliefs as true Christianity or true philosophy, not as a separate “Gnostic religion” per se. This underlined that “Gnosticism” is largely a modern scholarly construct, applied retrospectively.

Mid/Late 20th Century: New Perspectives and Public Interest.

The flood of new material from Nag Hammadi invigorated scholarship and also captured the public imagination. In the 1970s, scholars convened to reassess definitions: a conference at Messina (1966) attempted to narrowly define gnosis vs. Gnosticism – proposing “Gnosticism” be reserved for those 2nd-century systems featuring a Demiurge and secret knowledge for an elite. This definition, however, proved too narrow and was later abandoned, as the Nag Hammadi texts showed that the boundaries of what counts as Gnostic were fuzzy and that such movements bled into earlier and later periods (e.g. pre-Christian or medieval phenomena). Instead, scholars began classifying the texts by specific traditions: Sethian, Valentinian, Thomasine, etc., rather than assuming one grand Gnosticism. Important compilations and analyses were published: e.g. Bentley Layton produced The Gnostic Scriptures (1987) with translations, and Kurt Rudolph wrote Gnosis: The Nature and History of Gnosticism (1977, Engl. 1983) summarizing the state of knowledge post-Nag Hammadi. Perhaps the most famous work to emerge was Elaine Pagels’ The Gnostic Gospels (1979), which brought the discussion to a popular readership. Pagels tried to show how early Church authorities suppressed these alternative gospels and theological viewpoints to solidify a singular “catholic” doctrine. Traditional Christian apologists and clergy criticized the elevation of Gnostic texts, arguing that these were late fabrications or theologically dangerous interpretations. This controversy mirrored the ancient dispute: once again, Gnosticism was seen by some as a threat to orthodoxy, while others saw it as an enlightening alternative voice from early Christianity. The late 20th century also saw additional textual finds. Though nothing matched Nag Hammadi in scale, a notable discovery was the Codex Tchacos, which surfaced on the antiquities market and was published in 2006. This codex included the Gospel of Judas – a text mentioned by Irenaeus but lost for 1700+ years. When unveiled, the Gospel of Judas made headlines worldwide: it portrayed Judas not as a villain but as Jesus’s trusted disciple who understood the true gnosis. Such finds further deepened public interest in Gnosticism and underscored the richness of the early Christian archive beyond the New Testament. By the end of the 20th century, “Gnosticism” had become a familiar word, inspiring novels, films, and spiritual movements (some New Age groups even claimed to revive Gnostic practices). Yet within academia, this popularity came with a more critical scrutiny of the term itself.

Debates over Definition – Rethinking “Gnosticism”:

In the 1990s and 2000s, a shift occurred regarding the category of Gnosticism. Scholars questioned whether “Gnosticism” is too blunt a label to accurately describe the myriad sects and ideas it has come to encompass. In 1996, Michael Allen Williams published Rethinking Gnosticism, which argued that the term “Gnosticism” is a scholarly construct that might be hindering understanding. Williams pointed out that many traits scholars ascribe to Gnosticism (such as radical dualism, anticosmic pessimism, elitist knowledge) are not present in all so-called Gnostic groups, and conversely many of these traits appear in groups not traditionally labeled Gnost. He noted that gnosis (knowledge) was a widespread concept in antiquity, present in various religious traditions, not just the ones we label Gnosti. Williams provocatively suggested scrapping “Gnosticism” as a taxonomical category and replacing it with a more precise descriptor like the Biblical demiurgical tradition (focusing on movements that taught a subordinate creator figure). In 2003, Karen L. King published What Is Gnosticism?, which traced how scholars (beginning with the ancient heresiologists and up through modern times) effectively created the notion of a monolithic Gnosticism by defining an “other” to a pure orthodoxy. King argued that this process distorted the evidence – early Christian diversity was cordoned into orthodox vs. Gnostic in a way that may be more reflective of later power dynamics than of actual first-century realities. Both Williams and King urged caution: rather than assuming a fixed entity “Gnosticism” warring against “orthodoxy,” historians should study each group in its specific context (Syrian Christian, Egyptian, Jewish-Christian, etc.) and be mindful of biases inherited from the polemical labels of the past. The impact of this critique has been substantial. Many academic publications now avoid the term “Gnosticism” in their titles, preferring to speak of, say, Nag Hammadi studies or early Christian apocrypha. Some scholars have indeed limited “Gnosticism” to a narrow set of sects (e.g., the Sethians and Valentinians of the 2nd century). sometimes calling these the “classic Gnostics.” Others have proposed new categories altogether. For instance, scholars working on the Mandaeans or Manichaeans often treat those as separate religions, related but distinct from the Christian-oriented Gnostics. A number of experts continue to use “Gnosticism” in a qualified sense, finding it useful as long as one remembers it’s an umbrella term. The debate itself has become a major part of contemporary scholarship: examining how our understanding of Gnosticism has been shaped by the agendas of ancient heresy-hunters and modern historians alike.

21st-Century Global and Theological Perspectives:

Today’s understanding of Gnosticism is more global and nuanced. Academics from a variety of traditions (Protestant, Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Jewish, secular) contribute to Gnostic studies, each sometimes bringing different emphases. For example, Eastern Orthodox writers often approach Gnosticism as an archetypal heresy that highlights by contrast the Orthodox emphasis on the goodness of creation. Comparisons are drawn between ancient Gnostic ideas and modern spiritual trends: some theologians warn of a “New Gnosticism” in contemporary society (for instance, seeing transhumanism or radical individualism as denying the goodness of the body, a classically Gnostic trait). Such analogies are controversial, but they show the lasting theological interest in Gnosticism’s legacy. In the academic realm, interdisciplinary research flourishes. The Nag Hammadi texts are now studied not only for their theology but also for what they reveal about social history (e.g., the status of women in Gnostic groups, since some texts have female divinities like Sophia), about interactions with Judaism (many Gnostic works re-imagine Genesis and other biblical stories, often inverting their meaning,and about the diversity of early Christian literature. Scholars like Birger Pearson, David Brakke, and April DeConick in recent decades have continued to refine our picture of Gnosticism’s varieties, including proposing that some Nag Hammadi writings represent an originally non-Christian (perhaps Jewish or Platonic) Gnosis that was later “Christianized.” On the other hand, experts like Simon Gathercole have reasserted the later dating and derivative nature of Gnostic gospels vis-à-vis the New Testament, keeping the controversy over their historical value alive. Major archaeological work also continues – for instance, efforts to locate where the Nag Hammadi books were used or buried, and analysis of newly found fragments (with modern imaging techniques sometimes recovering unreadable text from damaged codices). The field has specialized sub-areas such as Mandaean studies, Manichaean studies, and Hermeticism, but all contribute to the broader puzzle of Gnosticism’s place in world religious history. Crucially, modern scholarship recognizes Gnosticism not as an isolated Christian deviation but as a cross-cultural phenomenon: it interacted with Platonism, with Second Temple Judaism, with Egyptian religion, and later with Islam and medieval thought. This global perspective has even led to comparisons outside the West, e.g. parallels between Gnostic myths and certain Buddhist or Hindu concepts (suggesting perhaps universal psychological motifs).