Power Structures in Not to Mention Camels (1976)

- Jon Nelson

- Sep 21, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 22, 2025

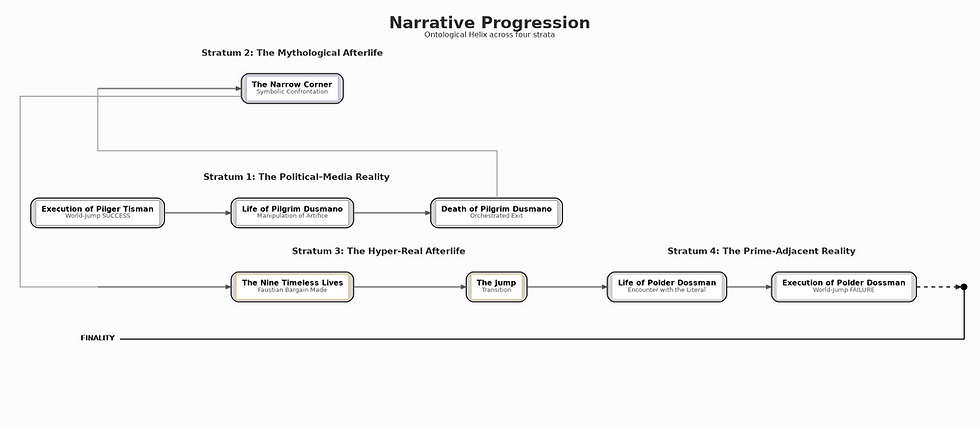

Some advanced Lafferty. I find Not to Mention Camels a hard book. Its components are easy enough to understand, but understanding what Lafferty is doing and how it fits together is challenging. One way to model the main conflict is to map it as being directly about good versus evil. Another is to step back and see it as a clash between fundamentally different and incompatible power systems, each vying for dominance within the derivative media bubbles of non-Prime realities. These power systems exemplify the good and evil in their strategies.

What makes the book especially demanding is that Lafferty presents a metaphysical vision of the world from the derivative point of view. All in Not To Mention Camels is secondary, contingent—derivative—of what is itself derivative and contingent: the created world. Within this derivative-of-a-derivative, the Creator of Prime is dramatically offstage.

As far as I can recall, this formula is unlike anything else in Lafferty. Lafferty situates his novel not in a faux version of Prime—the real world created by God—but in its proliferating third-order derivatives, the worlds spun off from that consensus creation. Prime itself is derivative in one metaphysical sense, for it is God’s creation, not God Himself. The derivative worlds of Not to Mention Camels are derivatives of that first-order creation’s creation. They are third-order counterfeits. What never appears, and cannot appear, within these counterfeits is the Creator in derivative form, for that would reduce the uncreated source of all things to the status of a created counterfeit—a contradiction in terms, and thus a logical impossibility.

I think the novel is built to exploit and explore this imbalance, making it one of Lafferty’s “what if Gnosticism were true?” experiments. This time, though, Lafferty separates the Gnostic cosmos from our cosmos of Prime radically. What do I mean? ‘’Snuffles” (1960) can be read as a kind of Gnostic pocket dimension of Prime in which an unlucky planetfall transpires. In theory, mediation could happen. Not To Mention Camels is not like that.

With this in mind, I want to sketch one way into the novel’s design: by tracing how it inverts the usual relation between antagonistic and protagonistic forces. In another Lafferty story, a figure like the Polder schizo-gash would almost certainly be cast as the structural antagonist, yet in Not to Mention Camels he is our protagonist—one reason the book feels so disorienting. Arrayed with him are all the powers of evil, what I’ll call the “Left Hand of God” faction, set against the opposing force, the “Even Hand of God” Gid (Noah, Consul Evenhand, the muddled kid, and others). The result is that Good and it’s God plays the role of antagonist. The justice revealed at the book’s end is treated as if it were happening to a narratological protagonist—known by turns as Pilgrim, Polder, and so forth—and so it registers as both metaphysical horror and black comedy. That horror fits, for it is precisely what it means to embrace the condition of a damned soul in hell: a Divine Comedy felt from the wrong side of judgment, as it were.

Before going further, I want to pause to address a complicating factor in this already very complicated novel. At several points the narrative turns meta-metaphysical, but we need to set aside those large set pieces—the Narrow Corner and the Nine Worlds—to focus entirely on the primary in-text environment we observe (since Prime itself remains violently off stage). These are proximate derivatives of Prime. Let's call them metastable derivative world arenas. Arenas are branch-worlds or crossroad-worlds: realities defined precisely by their lack of hard consequence, the spaces the anti-God protagonist enters through his repeated death-jumps. Their arena physics are unstable; as Doctor Funk says, “nothing ever winds all the way down without winding something else up.” These are Gnostic playgrounds, and they let Lafferty dramatize one of his recurring master-ideas: belief shapes will reality with few checks. That contrasts with the protagonist’s real antagonist—the ordered, Creator-governed world of Prime, which is always about the big checks: Heaven and Hell.

Pilgrim Dusmano knows that Prime is the one locus where “logic would prevail . . . It is one-dimensional and one-directional. It would be murderous to such a man as myself . . . They keep accounts on Prime World; ultimate accounts, I mean. They keep crabbed, careful, fetishistic accounts.” The Arena worlds, by contrast, are bubbles of suspended disbelief. The goal of The Left Hand faction inside such a metaphysical bubble world is to control its consensus reality without making it pop, or to avoid blipping out through death, which is a kind of non-final pop, a losing of the metastable arena game. The Camels protagonist keeps losing—after all, he keeps having to jump—and the worlds get worse each time, in theory rearview mirror and out beyond the windshield.

So what is the main resource for both the Left Hand faction and the Even Hand faction? Let’s call it “Latent Collective Belief,” anti-amnesia serum, Lafferty’s “oceanic”: the raw, undirected psychic energy of the masses, the collective unconscious, the sediment of archetypes, which can be manipulated through media distortion. One aspect of it is the mob’s craving for spectacle and meaning, the same public the Media Lords exploit when they “pour the enlivening action into the people; they pour it into all the senses and all the intuitions. They become the churning blood of the bloodless people; they are the deviled brains and the spastic spleens and the goatish gonads.” If the bubbles are also media systems, then this is both the prize and the medium of the arena conflict.

If you look at the right-most, dominant path of the diagram, you see it models the protagonist system. He is a "High-Gain Belief Transducer," converting the low-grade energy of collective belief into high-impact, manifest power. Cheap and spectacle oriented. He is a ruse, a techno-Machiavellian, a high priest of cultic gnosis. His instrument has a twofold operation.

First, its "Hollow Core" with "Zero Internal Resistance" is its most critical feature. By the end of the Camels, we find out that the protagonist is (or has become) an eidolon, an artificial man; Hector Bogus sees him clearly as a “miniature effigy, a badly made one,” and the doctors at his final death find him to be a composite of “eidolon fiber, human flesh, regressive or camel flesh all mixed together.” Thislack of a "real" soul self with moral or logical convictions has been driving the character into perdition. The formula goes something like hollowness = privation = evil. Evil licenses how The Left Hand faction channels the desires of the collective without minimized moral friction. The protagonist is a conductor.

Second, the conducted immoral energy is processed by the "Charismatic Amplifier," which is cultic/media-oriented performance. This is the protagonist public persona: “the man with the shimmer, with the dazzle about him . . . the hypnotic man, the electric man, the magnetic man, the transcendent man.” Through rhetoric, manufactured miracles, and ritualized violence, he imposes a coherent signal compelling to his followers. The output is "Manifest Power"—the force so strong it can create cults, topple governments, and move mountains. This is the power that the protagonist wants to use to "Seize Control" of the Arena's narrative.

The left-hand (intentionally flipped) subordinate path models the side of “Good,” Noah, the Consul, the murdered child. In these secondary arenas, the antagonist is a "Low-Gain Legitimacy Engine," trying to process the same input of collective belief. Its core is "Solid" with "High Internal Resistance." This is the antagonist’s integrity, goodness, fixedness. It is “real being," "certified so" as a man of "innocence or goodness or spotlessness," as Lafferty writes.

Privation/evil is not driving the antagonist, so he cannot serve as a vessel for the mob's chaotic desires; his own reality gets in the way. His "Formal Authority" shell, derived from law and morality, is the correct and legitimate source of power in an ordered world, an ideal Prime. But within the arena of a derivative world, which runs on spectacle, his source of power gets no purchase. It’s a signal that cannot be processed by the system. The public has no use for ordinary goodness when offered a “devil-revel,” which is why in the derivative media-world arenas the peak experience is “to destroy a high person if he is good . . . ‘It is more pleasure to kill one good man than a hundred indifferent men.’ . . . This is folk-knitting to form red history.”

So what is the outcome of this contest? The entire setup diagoses an Eidolon Engine, and the engine’s victories are always pyrrhic. While the Eidolon can successfully seize "Narrative Control of the Arena," the external "Prime Principle"—the absolute reality of logic and consequence—exerts constant ontological pressure on the entire third-order system.

An Eidolon Engine's power is based on escalating artifice; to prove dominance and maintain the belief of his followers, the protagonist must gin up ever-greater spectacles, a process which culminates in the novel's parodic mountain-moving. The hecklers goad him with the ultimate challenge, the “one proof you cannot fake”: “Mountain-moving!”

Ultimately, the protagonist creates the one spectacle—a witness to the absolute, undeniable power of the antagonist—that the artificial environment cannot support: “The mountain rose and moved in its full weight and mass. There was earthquake, there was airquake, there was skyquake.” But this triumph causes the Arena's narrative to pop, leading directly to the dissolution of the protagonistic force: “The mountain-moving incident had marked Polder Dossman’s highest height. From then on, he went down rapidly. And at once . . . Mountain-moving will always set up an equal force in the opposite direction, and the effect of that equal force was to dissolve the Dossman cult.”

Again, this is only one part of the larger picture. I’ve written elsewhere about how the protagonist undergoes a passage from flesh to Eidolon. With Lafferty there is always so much going on.