"Thou Whited Wall" (1974)

- Jon Nelson

- Jun 2, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Sep 21, 2025

“The eyes of it were the last remnant of the real Pilgrim, and now they’re dead.”

The other day, I posted about noetic darkening. Today, I want to flesh out its details, as it appears frequently in Lafferty's work. The typical pattern looks like this. Lafferty embeds counterfiguration into the plot mechanics of a scene, or he makes epistemological darkening the structural center of the story. Often ingenious, it is usually framed in the dual language of light and flight, using metaphors of clarity, revelation, initiation, awakening, and ascent. But the opposite has taken place: a diminishing character is losing the good of intellect. And with that loss, access to moral and spiritual goods is blocked. Because the intellect is the real light that lets the soul recognize truth, and truth is the condition for choosing the good and embracing the divine, once that light is dimmed moral judgment falters and the pathways to spiritual communion disappear. Lafferty himself explains this condition in Not to Mention Camels, noting that “the Media represent the anti-intellect” and their spread is “the anti-illumination.” This reversal leaves his characters truth-starved.

In what follows, I’ll look at how Lafferty uses noetic darkening as a structural motor in both Not to Mention Camels and “Thou Whited Wall,” and how his satire might speak to later media-systems theory. Much of his late work returns, again and again, to the problem of living with mass media. It helps to read him with some model in mind, so I will propose one existing model that fits particularly well. Even a rough frame will allow us to draw comparisons and trace how his ideas evolve. This is a first step toward that kind of reading.

When media form the atmosphere of one of his works, noetic darkening is usually the weather system. It gives the fiction a dark, saturnine, and ironic edge. Lafferty uses it to make moral points without ever sounding shrilly moralistic, even as he heightens both the high hilarity and the bloodsmell. In this, he is in good company. Jonathan Swift once wrote, “Last week I saw a woman flayed, and you will hardly believe, how much it altered her person for the worse.” Moral vision comes into focus through rhetorical violence.

It is fair to say that in Not to Mention Camels, Lafferty chose to build an entire novel around noetic darkening. That choice makes the book demanding—at times, exhausting. For me, it is the most exhausting of his works. As a character study, it keeps breaking its protagonist apart, hollowing him out just when it seems there is nothing left but dry bone. Lafferty never lets the Pilgrim/Polder character understand what is happening to him. At a key moment, he writes, “He was fuzzy and witless and confused . . . He did not know his own name, nor where he wanted to go or, more important, where he did not want to go.” The result is disorientation—for the character and for the reader.

One can see why the book never became a favorite. Most readers expect a character to develop. They expect the plot to move toward anagnorisis, the moment when story and self converge and recognition breaks through. In Camels, Lafferty turns away from all that, not by accident but by design. The novel anticipates his later doubling down, his full commitment to writing exactly what he wanted, without shaping his work to meet conventional expectations. That does not mean he was unwilling to accept editorial suggestions. In one letter, he wrote that editors are kind of dumb, but that is only because everyone is kind of dumb.

Nonetheless, of all Lafferty’s novels, I think this one is the hardest to discuss. Almost nothing substantive has been written about it, yet it continues to fascinate serious Lafferty readers. For me, its power lies in a claustrophobic cosmology: alternate realities sealed off from heaven, with no trace of the beatific vision. It is pure noetic darkening. Pilgrim calls Prime World “murk . . . mud . . . miasmic fever,” a suffocating basement of being. And yet it is the other worlds that lack any opening to something higher than Prime, while Prime is the one place the protagonist most wants to avoid. If he dies there, he might go straight to hell.

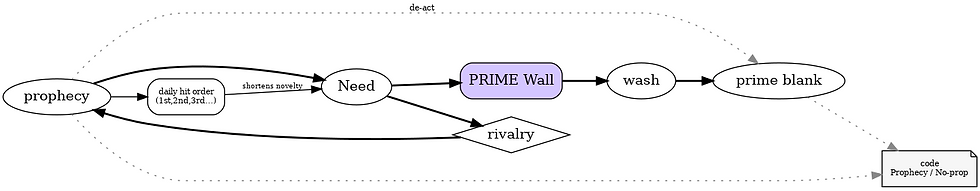

In addition to being a mystical black comedy, the novel presents a strange media ecology. It draws on Gnosticism and Western hermeticism while also scrutinizing mass spectacle. I have included some notes on this aspect of the novel on the Resources page, but the overall effect remains strange and bewildering. Even if one sets aside the gnostic and hermetic elements, the in-world media system itself is difficult to piece together. If you are like me, you want to see how it fits together.

Let me give you one example: the role of the Eidolon Lords and the Media Lords. They control the culture industries of several worlds, but the novel never explains how their roles change from one world to the next. It also fails to make clear how the two groups differ. Do the Eidolon Lords create ideas while the Media Lords spread them? The novel does not say. It does not even offer enough for the reader to form a confident guess.

The deeper we go, the harder it becomes to sort things out. Some characters belong to both groups. All are described as “the true Lords of Unreason and Darkness.” So much noetic darkening occurs that the reader ends up stumbling through the media space, trying to understand how it all connects.

One connection, however, does seem clear. The novel reflects the years in which it was written.

Which is to say that Camels and “Thou Whited Wall” should both be read as works conditioned by the early to mid-1970s. By that time, Charles Manson was old news. The counterculture had turned to the occult, often softening it into New Age spirituality. Meanwhile, the country was caught in the Watergate crisis. From the folk-horror strangeness of 1971’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw to the mass-market spectacle of 1973’s The Exorcist, the powers and principalities had entered mass culture with fanfare.

I have wondered if Lafferty sensed that something in the novel’s media critique did not quite hold together. His notes in the Tulsa archives show that he completed Camels on February 15, 1974. In November of that same year, he returned to the theme of media ecology with “Thou Whited Wall,” a story that can be read as the novel’s little sibling. Where Camels stretches the problem of mass media across hundreds of pages, the short story compresses it into a single day-long media feedback loop.

As with Camels, the short story focuses on the media system and the noetic darkening that comes with it. In the novel, the protagonist increasingly resembles a media construct. The short story, in turn, dissects the loss of self through media saturation. On one level, “Thou Whited Wall” is a gleeful parody of demonic infestation. It plays along with the popular culture of the first half of the 1970s. On another, it delivers an acidic critique of the media itself.

As you probably know, the story's title refers to two well-known biblical episodes about walls that have nothing to do with each other. It is the kind of lateral leap only Lafferty would make. In Daniel 5, a mysterious hand writes the words "Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin" on the wall of the palace in Babylon. The message is visible to all but understood only through Daniel's God-given interpretation. It declares that King Belshazzar has been "weighed in the balances and found wanting" and that his kingdom will be divided between the Medes and Persians that very night. The writing reveals the emptiness behind Belshazzar and foreshadows his downfall. Lafferty twists this. In his story, the messages on the walls are easily readable, and the demonic writers are referred to as prophets. It is a major act of Lafferty's approach to counterfiguration.

The other biblical episode takes place centuries after Daniel, in Acts 23. Echoing Jesus' rebuke of "whitewashed tombs" (Matthew 23:27), Paul calls the high priest Ananias a "whited wall." This is a direct condemnation of religious hypocrisy, especially the kind that hides injustice beneath a polished surface. Taken together, these two "walls" warn that nothing can protect those who defy God's justice once His verdict is made public.

At this point, the short story does differ from the novel in a key way. "Thou Whited Wall" gives the reader a clear and easy-to-follow media ecology. It tells the story of a single day in the life of Evangeline Gilligan, who lives in a society where "guided persons" structure their lives around messages that appear on public walls. These messages are written by so-called "prophetic artists." Her husband, Mudge Gilligan, who is also guided, kills himself after a message tells him to. He has just lost a twelve-dollar bet. Later that day, their son Hiero uses a suicide kit to end his life, along with several friends. Through it all, Evangeline goes about her routine (her job, her conversations) with a calm that reflects her guided condition.

My favorite media theorist isn't a media theorist at all. He is a German systems thinker named Niklas Luhmann. His ideas help us understand this story, and for the rest of this post, I'll draw on some of his concepts. Luhmann is known for being highly abstract. His work is filled with interconnected technical terms that can sound like jargon if introduced too quickly. So, I'll keep to a few ideas that have a real payoff when applied to "Thou Whited Wall." These include operational closure, the distinction between information and non-information as a code of mass media, and the media's role in shaping social reality.

In The Reality of the Mass Media, Luhmann writes, "Whatever we know about our society, or indeed about the world in which we live, we know through the mass media." "Thou Whited Wall" takes this idea to an extreme. In the story, the "Handwriting on the Wall" becomes the mass media itself. Early on, Evangeline says, "Ah, but it's nice to be a guided person and have so much working for you."

That phrase, "working for you," is an ironic understatement. It refers to total media saturation. The media have colonized the guided persons. The wall messages are their only source of truth and the only guide to action. Their daily lives, their social structure, and even their understanding of life and death are shaped entirely by the walls.

This has both epistemological and moral consequences. All of it is tied to noetic darkening. At one point, Evangeline cannot understand that she has been fired from her job. At another, she fails to register the horror when the old demon Demogorgon casually announces he is off to rape some children.

Where I think Luhmann's theory sheds light on the story is in his idea that the mass media system operates on a binary code. That code is information versus non-information. In the story, the "prophetic artists" create what is treated as pure information. Their messages carry a kind of pseudo-divine, pseudo-fated authority.

By contrast, the views of "unguided persons," who see the wall messages as nonsense or pseudo-science, are pushed to the margins. Their voices are marked as non-information within the dominant system of the guided. This division reinforces the media's control. The walls carry all power. As the story puts it, "the guided people . . . had their power and their numbers." Reality itself is shaped by whoever controls the code, be it demonic "prophets" or Media Lords.

Closely tied to this is another of Luhmann's insights, one that strikes me as especially convincing. He argues that the information/non-information code in mass media is not about knowledge. It is about selection. Information is a choice from a range of possibilities. It reduces uncertainty for someone inside the system.

This brings us to a central idea that "Thou Whited Wall" turns on. For something to count as information, it must have an element of surprise. It must change the observer's state. Luhmann puts it clearly: "Information cannot be repeated; as soon as it becomes an event, it becomes non-information."

That Lafferty understood this well is clear in the daily ritual of the wall washers. Every dawn, the wall washers “obliterated every picture and scribble . . . and left the stark and challenging surfaces in their clean emptiness,” resetting the epistemic clock." This clearing of the walls ensures a fresh slate for each day's media cycle. The practice speaks directly to one of Luhmann's key points about mass media.

A core trait of information, as distinct from knowledge, is its newness. Once something is known, once it has made its difference within the system, it stops being information. It loses its function as a surprising selection. One thinks of Thoreau's characterization of news as gossip. Old gossip becomes part of what Luhmann calls the system's environment, more like the material of the wall itself than the message on the wall.

We see this demand for novelty in the story's nightly ritual. The wall washers come every late night or early morning. They clean and whitewash the big-name walls. They erase every image and every life-altering pronouncement. The guided persons wait eagerly to see who will hit the wall first that day. Their lives turn on these brief, system-generated novelties.

Take the suicide of Mudge Gilligan, Evangeline's husband. He reads the words of the Gloaty Throat on the wall and obeys them. The message carries power because it is new. It demands immediate action. It is not treated as a prediction but as a directive. That is what gives it weight.

This is not how knowledge works. Knowledge stays knowledge, whether it is new or not. But the guided persons have accepted a reality in which information has replaced knowledge. Their world runs on media logic. Their understanding is purely operational. It is a learned skill of decoding today's news, not a growing insight into the nature of the walls, awareness of the devils, or the cruelty of the system they serve. And the system is cruel. Satirically, the information they trust can never become knowledge. It will be wiped away by morning.

Lafferty's contempt for the system he depicts is visceral. You could make a checklist of all the filth that the white walls cycle around, from the feces of the "prophet" Hu Flung to the splattered blood of the Spanish Fly. By the time the story ends, the noetic darkening is total, with Evangeline having "everlasting compassion for all the unguided and unscienced people of the world."

Always careful with words, Lafferty gives us the beauty "unscienced," those who do not know. Evangeline Gilligan pities those outside the media system that has led to the death of her husband and son, and her detachment. And she sees the "unguided" as the ones lacking.

My favorite moment of noetic darkening in the story is a scene of iconographic insetting, where Lafferty's mastery of counterfiguration becomes razor-sharp. The demon-prophet Joe Snow communicates through white on white. Lafferty writes, "But Joe was always a time bomb. His hits were delayed messages. He hit with snow-shot, white on white, and his messages could not be read immediately. But his communications always caused flurries of intuitions in all who were on him for that day. And later in the day, when the whited walls had become dirty and speckled, his messages could be read as they stood out in stark white from dingy gray."

As Evangeline's day ends, she finds herself in the free-fall of Camels, the kind of descent that gets mistaken for ascent. "And the reproduction of the Joe Snow message was good, but there was still not enough contrast to make it readable. Evangeline had that snow-message imprinted on her own mind, however, and her mind had now become gray and grimy enough to give contrast. And she read . . . ."