“Apocryphal Passage of the Last Night of Count Finnegan on Galveston Island”

- Jon Nelson

- Jan 4

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 5

Finnegan had the barrel of the rifle in his hands. Then he had Saxon Seaworthy in his hands, far underwater in a turmoil. Saxon did not die easily or willingly. To lull the grip he went limp as though already gone. Then, thirty seconds later, he erupted with violent writhing so as to break away. It was not easy to throttle a man with so sinewy a neck that was also protected by the pherea, the throat protuberances of an old satyr: and to choke off the air of a man already underwater is of little effect. When Finnegan was able to hold Seaworthy with one hand, he raked down into a side pocket for his clasp knife and went to work on throat, under-ear gap behind the jaw-bone, and the intercostal slots into the thorax. He opened half-a-dozen fountains that gushed underwater, and he sealed it when he had the heart itself in his hands. Saxon Seaworthy did not have a proper grave, and it was not at all sure that he would remain buried. But he would remain dead.

Some notes on Argo.

At the last minute, Lafferty changed his mind. He wanted to add an ending to The Devil Is Dead (1971), not the ending we now know as “Diabolique,” but a further two thousand words that eventually took the title “Apocryphal Passage of the Last Night of Count Finnegan on Galveston Island.” By that point, however, the printing process was too far along, and the addition could not be made. Readers therefore received the novel as it stands, ending with “Diabolique.”

The new ending was an attempt to stitch together what would become the Argo legend. Had it been included, it would have sewn The Devil Is Dead directly to Finnegan’s death at the close of Archipelago (1979). The endings of each book would rhyme generically. As it happened, some of non-"Apocryphal Passage" material that Lafferty wanted added to The Devil is Dead eventually got spatchcocked into Archipelago.

Lafferty is a labyrinth. It will always be one of the curiosities of his fiction that The Devil Is Dead ends where it does, simply because the “Apocryphal Passage” was never added. And yet the ending we have is more than fitting. "Diabolique" is a perfect ending. It is one of Lafferty’s best poems, if not his best. It has been called a literary trick ending, but something so thematically elegant can hardly be a trick.

In a letter, Lafferty wrote, “The alternate ending wasn’t used in subsequent releases because I couldn’t decide whether it was better or worse than the original record. I still can’t decide whether it’s an improvement or not.” I think Lafferty had sound judgment here. The new passages would have weakened the integrity of the work as phantasmagoria, even as they would have brought greater coherence to the Argo legend. One must choose. In an ideal world, the text would be available as a supplement in all editions of The Devil is Dead.

Today, I want to try to work on some of what is going on here. Longtime readers of the Argo legend will most likely know this already, but it may be helpful to those who haven't yet read Argo. First, Archipelago and The Devil is Dead are less a sequence than a complementary set. Archipelago is the necessary backstory for Finnegan, making the surreal events of the complement novel understandable and emotionally resonant.

The Devil Is Dead can be understood in several ways. Here are some top options:

A stand-alone fantasy. The middle book of a trilogy. A drunken psychosis that never happened. One document among many in the loose constellation that makes up the Argo legend. An extended intermezzo set within the events of Archipelago.

I read it the last way.

Toward the end of The Devil is Dead, in the graveyard scene with Mr. X, the reader learns the truth about the two devils. Finnegan has been haunted by the impossibility of having buried Papadiabolous and his seeming resurrection. Mr. X explains away the mystery. There were twin brothers: the first was an evil revolutionary murdered by Saxon Seaworthy; the second was an Irish-American undercover cop named Noonan who impersonated his dead brother to infiltrate the gang. In a weird way, that means that the resurrection act in The Devil is Dead is something like a high-stakes police sting that ends badly when the “better” devil is murdered at Naxos.

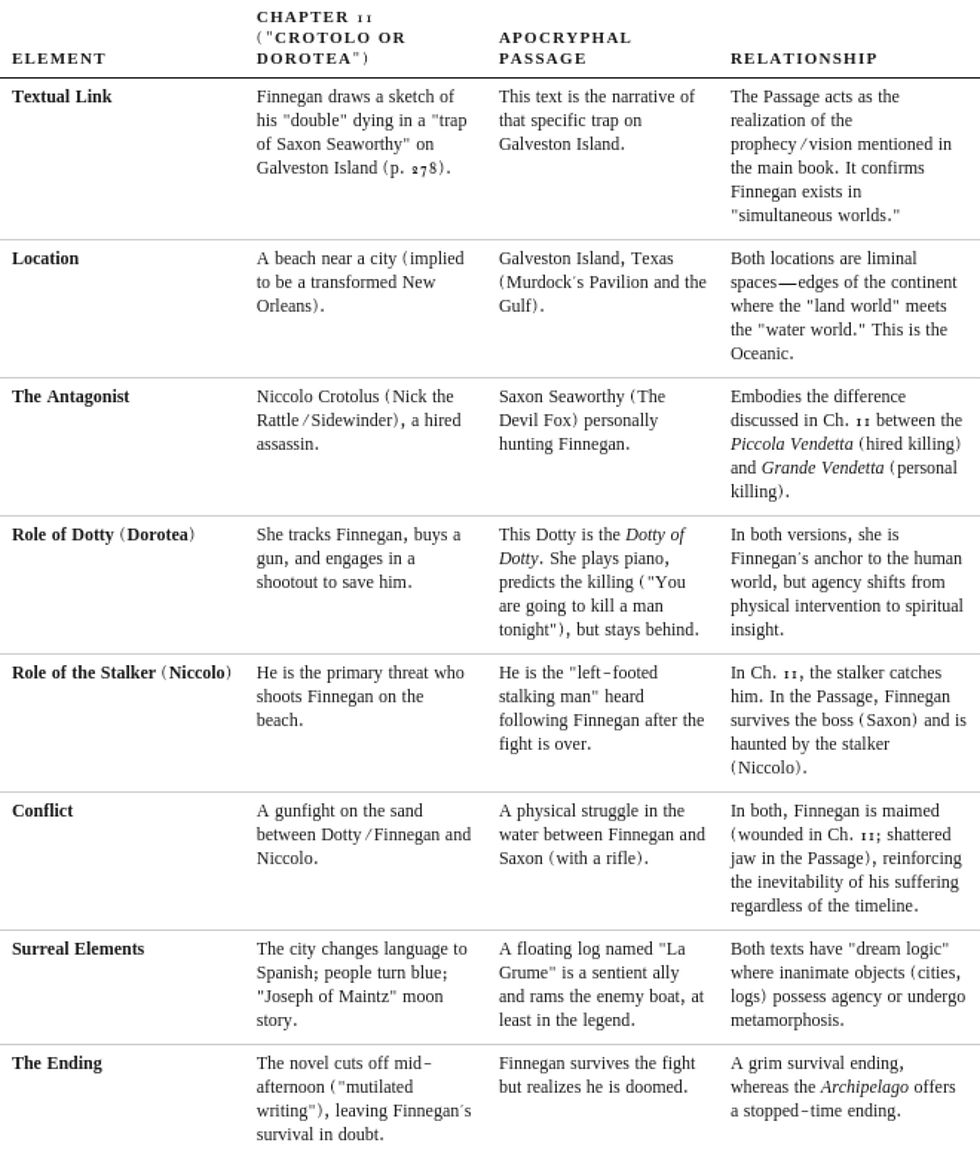

Archipelago sheds light on several of the ambiguous mythological elements in The Devil Is Dead. It supplies names and origins for threats that otherwise remain shadowy. For example, Archipelago identifies the left-footed killer in "Apocryphal Passage" as Niccolo Crotolus, a club-footed professional assassin in the employ of Seaworthy. At the end of this post, I’ll include a complete timeline for Seaworthy.

More importantly, Archipelago provides the necessary context for understanding Finnegan’s inner world. It offers something like a psychological portrait, or as close to one as Lafferty would give, while remaining fully a work of genre-defying reality-adjacent fantasy. The novel introduces the idea of the Other Race, a Neanderthal lineage concealed within human bloodlines. It accounts for Finnegan’s blackouts and his shadow life. The Devil Is Dead gives us the missing year, the period in which Finnegan lives out that buried inheritance rather than just suffering its effects, often in the form of hangovers.

So how does the “Apocryphal Passage” fit into all this? When included in The Devil is Dead, it alters the narrative in some profound ways. In the 1971 version, the novel ends poetically and mysteriously, with evasion and ambiguity. Finnegan leaves his antagonist alive and the conspiracy unmet. Without the “Apocryphal Passage,” a sense of paranoid fog, of shapes that never fully come into focus, runs from beginning to end. The grave really is an enigma.

With the inclusion of the “Apocryphal Passage,” the novel achieves a closure that pulls pretty hard against the dreamy openness of the published text but clarifies its relation to Archipelago. With the inclusion, both novels end on grim noir-tinged notes. In the restored The Devil is Dead, Finnegan stops running. He lures Seaworthy into a trap in the Gulf of Mexico. They have a brutal underwater battle where he stabs Seaworthy in some of the most violent passages Lafferty ever wrote, ripping out Seaworthy’s heart. The full version shifts the ending from what amounts to Finnegan being an escapee to that of being a permanently hunted man. That hunt? It reaches its terminus in the final pages of Archipelago, where the left-footed killer (Niccolo Crotolus) corners Finnegan on a beach.

The violence of the “Apocryphal Passage” accounts for why the assassin in Archipelago is so relentless; the piccola vendetta mentioned in Archipelago is the counterstroke to Seaworthy's murder, Seaworthy who is of devil lineage himself. The Devil is Dead gives us the offense; the shootout at the end of Archipelago gives us the payback. An eye for an eye.

This probably is a good place to say something about what has come to be known as the interglossia. It is a short paratext in the form of a letter written by Lafferty’s character Absalom Stein. The letter is full of speculation about Finnegan's nature, questioning whether he is merely a character or a vessel for something else: “Are we not sometimes reduced to being no more than items in the mind of Finnegan?”

Although first published in 1989—printed at the beginning of Dan Knight’s edition of How Many Miles to Babylon—the letter dates from the same period as the “Apocryphal Passage.” In Lafferty’s last-minute intended structure, the letter would have been a part of The Devil Is Dead, not put at the end, but placed between Chapters 10 and 11.

That placement is significant. The novel’s major structural seam runs between those two chapters. It is the book’s turnout point: the plot stops closing in on Finnegan in the way it has through the first half of the book, and the plot is redirected outward through him. Several online reviewers have complained that the novel's second half drags or doesn’t cohere. If the novel doesn’t work for some readers, some of that comes down to not having access to the interglossia and the “Apocryphal Passage.” Not having read Archipelago will also be a large factor.

Without the interglossia, and with no Archipelago yet in print, Lafferty had to trust that dream logic of The Devil is Dead would be like a blind rivet holding the two halves of the book together. He knew something was amiss. He said the book had a broken back. If so, then the interglossia is a bag of spinal pins, rods, and screws. Had the interglossia been included, there would have been support for readers as they passed from the first to the second half of the book. Because the book is so unusual in so many ways, it makes sense to have a waypoint that gives orientation.

With the interglossia, Finnegan’s under life in The Devil is Dead falls into two clear phases: first, a mix of Chestertonian nightmare and romantic adventure; then, a mix of nightmare and harder, Lafferty noir. The nightmare/romantic adventure ends with what the book calls “the first death of Finnegan.” At that point, Anastasia is dead, having been murdered. “Several years had gone by,” Lafferty writes, and the reader is dropped, with little transition, into a more cynical phase of the story that pays off in the “Apocryphal Passage,” in the bloody revenge, which, of course, did not appear in 1971.

In the interglossia, Lafferty also tosses the reader a lifebuoy in the form of a concept: the “double phougaro,” the double funnel—and he identifies Finnegan as one these. The image does more than explain Finnegan. It explains both the world-building and the book’s construction.

Metaphysically, Archipelago and The Devil Is Dead stand in a double-funnel relation. Again, a complementary set. There are two settings, but also two realities that taper into a single point of passage and then widen back out. Finnegan is that passage: the place where one world can become “inside” and the other “outside,” and where that can reverse. Stein notes that Finnegan “believed that he was subject to topographical inversion . . . that one of the worlds was always interior to him and another one exterior, and that they sometimes changed their places.”

Metafictionally, because Finnegan is the conduit, the narrative is organized around him as the double funnel’s neck. When he flips through amnesia, topological inversion, or the swapping of inner and outer—the text flips with him. Stein puts it this way: “Finnegan is a double phougaro or funnel, the link between several different worlds,” and Finnegan’s own descriptions (“when I move from one life to another,” “an upper and a lower life”) read as the subjective symptom of the artistic form.

Returning to the break between Chapters 10 and 11, one moves between literary biomes—geographically and atmospherically. There was the Old World mythic, oceanic mode; there will be the New World noir mode. So, from the ancient, moonlit ruins of the Greek islands to the neon-lit verticality of the modern American city. Where there were oreads and satyrs, there will now be a "small hotel of curious gothic style" where darkness is modified only by a "neon ambient."

The prose recalibrates as well. Gone is the claustrophobic languor of the sea voyage. Gone is the scene painting and some of the Lafferty word music. Time and tempo enter the novel in a new way now that genre has shifted because genre organizes time. There is the jog-like, punchy rhythm of a heist or revenge novel—still unmistakably in Lafferty’s voice, still offbeat. It is the difference between drifting on a ship and clinging to the side of a building like a living gargoyle, ready to break a window and commit murder.

I read this as a change in the novel’s representation of agency. Again, Lafferty uses genre to point it up. Throughout the first ten chapters, Finnegan is largely reactive: a passenger on the Brunhilde, bewildered by the conspiracy that surrounds him, and—most importantly—the one being hunted. The paranoia is centripetal, tightening around him and steadily narrowing options. The first half is about powerlessness and loss.

Chapter 11 reverses that dynamic. Finnegan stops being pushed around by events and begins to lead them. He hunts Saxon Seaworthy, accepts his monster blood ("It was nighttime, and Finnegan had gone feral"), and shows competence. The action becomes more centrifugal: instead of the world closing in on Finnegan, Finnegan moves outward, pursuing and imposing his will. With that change in agency comes an inevitable change in the book's texture. The murdered Anastasia belongs to an older order—mythic and backward-facing love rooted in the past. Doll Delancy is pragmatic.

All this is growth for Finnegan, but the gain comes at a cost. Most readers seem to find the second half less aesthetically satisfying. It is far less phantasmatically claustrophobic and more generically constrained, albeit still wildly offbeat. The more decisively Finnegan acts, the further he moves from the earlier bedumbed Finnegan, who was a relatively passive and disoriented vehicle for identity horror. He is close to the kind of identity dissociation he experienced in the hospital with private Gregory in Archipelago.

What seems clear to me is that once the noir machinery takes over, the metaphysically destabilizing phantasmagoria of the identity horror recedes. The novel begins an ascent that will converge with the noir logic that closes Archipelago, where Finnegan is gunned down. Lafferty's noir mode, which he explored in short fiction and in Mantis, can then be thought of as a middle term. It is the bridge passage through the double funnel. That makes the “Apocryphal Passage” one possible right ending for The Devil Is Dead, and it also explains why it pulls against its more oceanic first half.