"The Only Tune That He Could Play" (1976/1980)

- Jon Nelson

- Oct 3, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Oct 4, 2025

They had been in the large, unconscious, amitotic environment of intense activity kept well below the surface. It was there that the requisitions for sons were fulfilled; it was there that the selections were made as to what things should rise above the surface, what things might be kept in harmless somnolence below thesurface forever, and what things must be destroyed while they were still below the surface to prevent them from making trouble later. So it was that the boys broke up through the surface of that environment with bright memories in some areas, and with gappy holes in their memories on other sections. Into the holes in their memories, other sorts of things might be flowed during the instructions, things of unrelated substance.

“The Only Tune That He Could Play or Well, What Was the Missing Element?” is intensely personal. Its title might just as well describe Lafferty’s Ghost Story. The final sentence speaks of secrets and anti-secrets, a macro-lesson in how to read Lafferty, and we should listen. What unites the variety of his work is the sense that reality is rarely seen. This can arise because one is split or ghostly oneself, or it can arise through conspiracies, strange physics, diabolical machinations, gnostic or demiuric entrapment, world-ending apocalypses, ideological acts, radical recontextualuzation, and so forth. There are hundreds of variations across the millions of words he wrote. In this sense, almost every Lafferty story is an anti-secret pointing to a complementary secret in Prime. The exception, perhaps, are pre-nucleation stories and novels and the four collaborations. There exists a fact or situation that someone—or something—doesn’t want the Everyman to know. That’s you. It coincides with how Lafferty takes reality to be. That’s him.

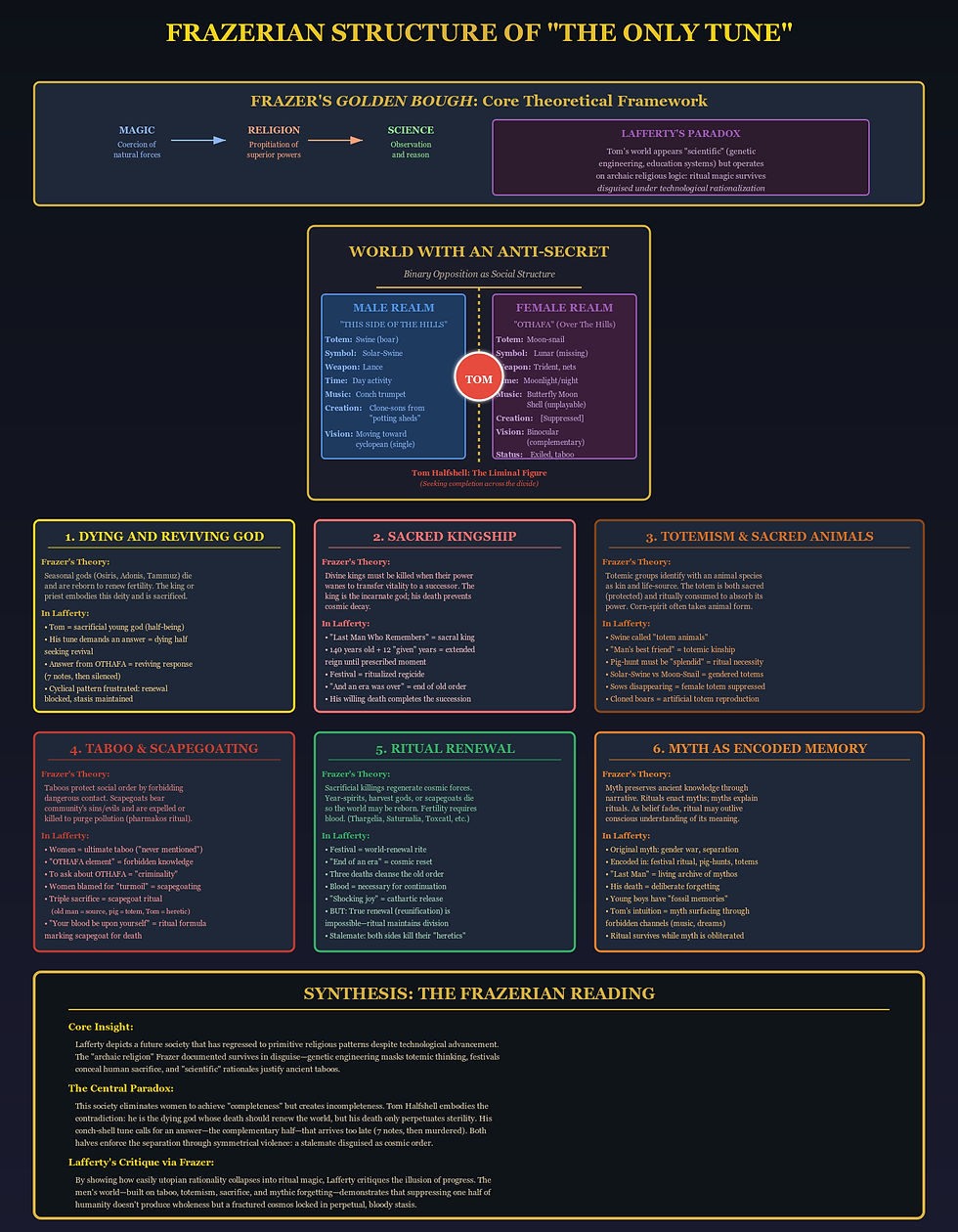

Lafferty obviously built “Only Tune” around his understanding of Sir James Frazer. I’ll share some notes on that at the end of the post. For now, though, I want to focus on the idea of Lafferty stories as anti-secrets. To get there, what actually happens in this very underappreciated story?

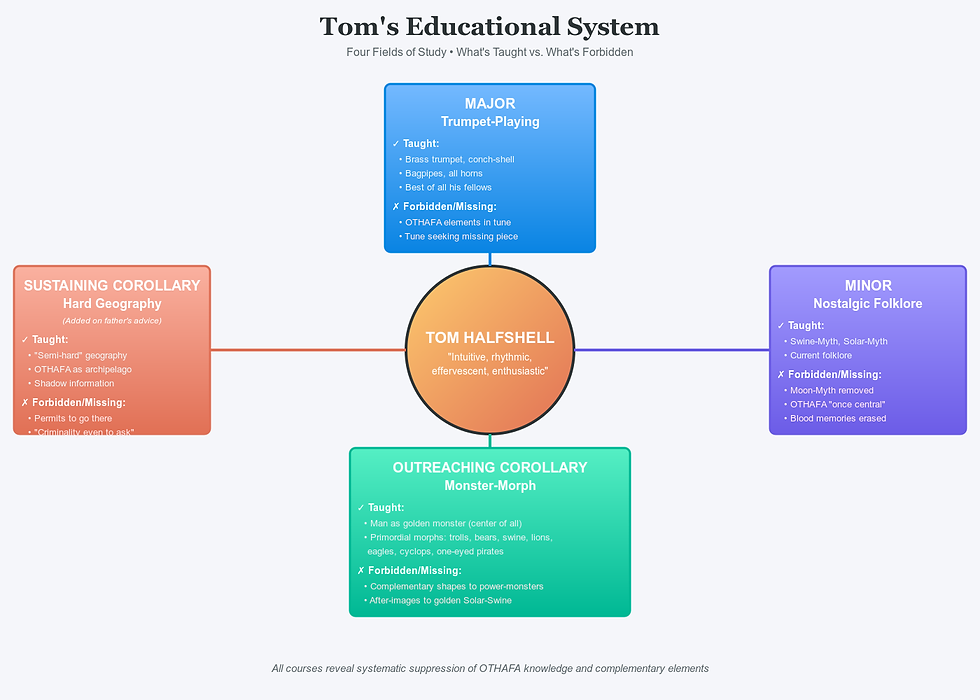

Tom Halfshell is a cloned twelve-year-old in an all-male society. He’s also incomplete. His father criticizes his studies in Trumpet-playing and Nostalgic Folklore (in the story, this is authentic history) as too soft, urging him to "introduce a harder and more manly element" into his life. Though Tom is an intuitive, rhythmic, and effervescent kid, he "just wasn't very intelligent." His friends, who are all manly boys, see his deficiency.

One of the joys of the story is the characters' hog hunting by riding mules. They do this with lances. It brings to mind all the feutered lances in Sir Thomas Malory and makes the absence of women in the story more felt. It is on one of the wild hog hunts that Tom’s friend Cob Coliath shouts, “You are an unmatched half, Tom . . . and ours is a world full of unmatched wholes. Complete yourself, Tom, complete yourself!” Despite this, Tom is a brilliant hunter. He’s the best of the lot, making more spectacular kills than anyone, a result of his "trickiness, a quality not much understood."

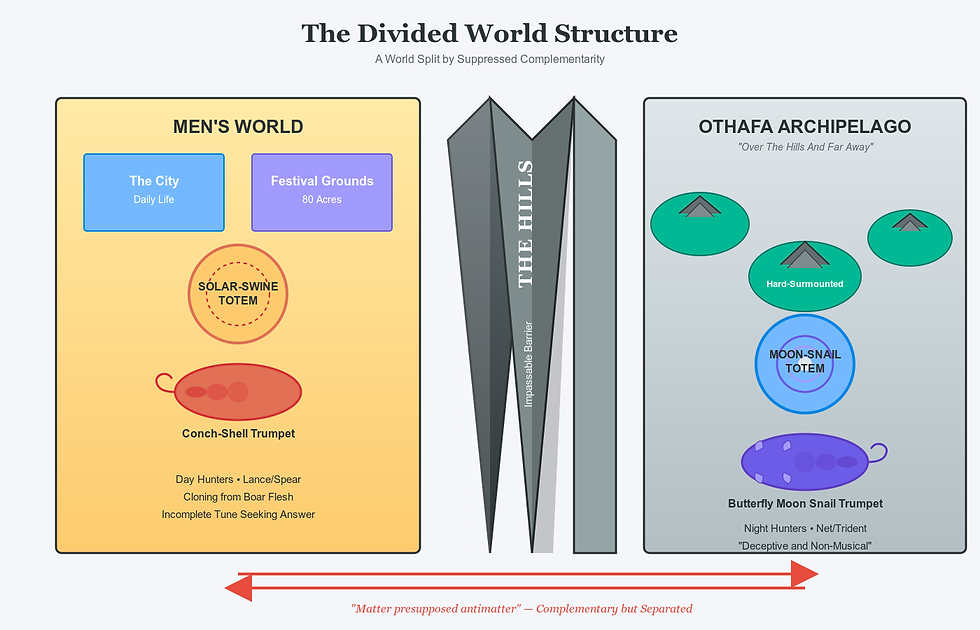

Tom's incompleteness is most evident in his music. He plays a conch-shell trumpet, and his friend Duke Charles says about this, “The way you play the conch-shell, it’s demanding an answer.” Tom replies, “Sometimes I think that I can hear that answer from over the hills.” His music instructor warns him that his tune contains "outlawed OTHAFA elements" and that by the "character of the world that we live in, there is no such missing piece." When Tom refuses to change his music, because he cannot do so and still be Tom, the instructor tells him, “Ah, I always hate to see a boy chopped down before he ever becomes a man. Your blood be upon yourself!” The missing part drives Tom to investigate his world’s censored history, where “Nostalgic Folklore was full of holes" and the land of OTHAFA, home to rumored creatures of the moon-snail totem, is a forbidden topic.

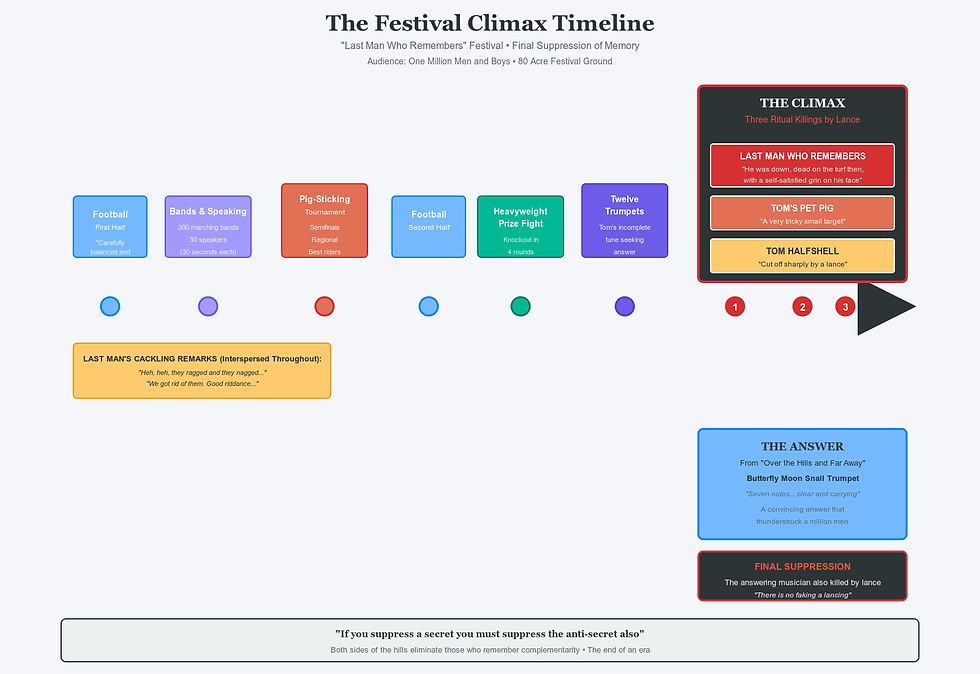

Everything converges at the ‘Last Man Who Remembers’ Festival, a huge, ritual gathering to celebrate the death of the last man who recalls the world before a fundamental change, i.e., a world where women were acknowledged. The old man, a "crowing, cackling little monster," entertains the million men and boys with his fragmented memories. “Heh, heh,” he cackles, “They ragged and they nagged. And what can you do with naggers and raggers? Get rid of them, that's all." Lafferty punctuates this part of the story with things like, "Ours is a world to be lived in. It is a complete world. It is the way we like it.” Tom is chosen as a Horn-Boy for the festival, where it is rumored that the incomplete trumpeter would have to be killed. He is a sacrificial victim, and Lafferty’s sympathies are entirely with him.

In the festival's climax, the Last Man, Tom's pet pig, and Tom himself are brought to the center of an arena. As "eleven of them fell silent, and a single one kept on with its strange tune," Tom plays alone, his conch-shell trumpet "still roaring and soaring." The Last Man cackles, "Heh, heh, they're well forgotten . . . Why, you couldn't even have a pig-sticking pageant with them around.” The best lancers then move in. They cut down the old man, then the pig. As Tom plays his only tune one last time, "it was cut off sharply by a lance."

Just after Tom falls dead, an answer to his music arrives, "distantly, but clear and carrying, from ‘over the Hills and far away,’ played on the unplayable trumpet-shell of the Butterfly Moon Sail." This seven-note answer is also abruptly silenced, "cut off sharply — by a murdering lance." Lafferty ends the story by revealing what we already knew, the identity of the exiled "anti-creatures" from the OTHAFA regions: "(what was the name of them when they still lived in this plane of the world? — Yes — ‘Women’)." Then he tells us about anti-secrets: “If you suppress a secret, you must suppress the anti-secret also.”

This is a longer story by Lafferty’s standards, and a rich one, so I want to pause for a few minutes on how the anti-secret usually works in a Lafferty story, then turn to some great awkward gold. The nature of the secret can profoundly damage his work, and I have tried to be clear and scrupulous in showing that this is not a trivial matter, because it is also the engine of the best things Lafferty writes. A great Lafferty story usually works by drawing us in through what Victor Shklovsky called ostranenie, or defamiliarization. This reveals the working of something secretive, a lost or distorted aspect of Prime. One way to read Lafferty, then, is to ask: if the story is an anti-secret, and if writing the anti-secret is a call-back to the secret in Prime—like the female calling back to Tom in this story—then what is the secret? Is it historical? Is it oceanic?

Consider a worked example, one based my last post on "Condition Quick." How is the story an anti-secret?

Working through the propositional content of an anti-secret is the process of discovering what a Lafferty story is really about. Concepts such as countersignifcation, iconographic insetting, phantasmataxis, noetic darkening, and theotropic dissonance are intended to help with this. They’re ugly-sounding precision instruments meant to sensitize a reader to Lafferty’s strategies, pincers for grasping slippery anti-secrets.

I’ll end by pointing to something any reader of “The Only Tune That He Could Play” should consider. Within its futuristic hog-hunting ambient, real history has been obscured by ritual and myth. Tom is a budding historian, but one enraptured by the mythical. In shaping this story, Lafferty cribbed from Sir James George Frazer (1854–1941), a writer he knew well, as his letters attest. Frazer, the Scottish anthropologist and folklorist, is now remembered for his monumental work The Golden Bough (1890-1916). It profoundly influenced writers such as T. S. Eliot, and I’d wager it now best known through cheap one-volume abridged editions put out by people who haven’t read it.

Look at an edition of The Golden Bough, and you will likely witness an ancient 20th-century ritual. The introducer will say here is a work that it is wrong, reductive, monomaniacal, and dated. Of course it is. It was monstrously ambitious. It was monomaniacal. It surveys myth, ritual, and religion across cultures. Frazer was a kind of non-functionalist forerunner to Joseph Campbell, one who wrote well, and an Edward Casaubon-type on a hobbyhorse, seeking universal patterns of human belief by comparing ancient myths and practices with Christianity. In the late 19th century, solar myths were in the air, and Frazer gave them particular emphasis. The basic idea is that many religious stories, deities, and rituals are symbolic expressions of the sun’s daily and seasonal cycles. They are myths of dying and resurrected gods, with festivals tied to solstices and equinoxes. This is said to be humanity’s attempt to explain and ritualize the sun’s power over life, death, and renewal. Hence the sun-and-swine motif in Lafferty’s story.

Lafferty does a lot with Frazer, but it is easy to miss something cunning about this: the 20th-century Frazer ritual. Lafferty knew full well that Frazer was deeply out of fashion. He would have been reminded of it constantly, even in his own edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. The very fact that Frazer and solar-myth talk were passé is part of the story’s point. Lafferty exploits Frazer nostalgia for the mythic—and all our modern history of thinking about the mythic—in his use of solar mythology. Why? Because here he is saying you should be nostalgic for the truth of history, which is mythic, which is religious. Whether one finds this congenial depends on how one views Lafferty’s larger project. I think he had something like this in mind in the following passage from the story:

“And the name of the course was the trickiest thing about it. Yes, it was very evocative of nostalgia: but there were so many sections of forbidden nostalgia. There were blood memories whose expression had been erased. And there was foolish stuff of poor quality that had been put in to fill the holes where something had been torn out by the roots. In particular was the land or plateau of OTHAFA blocked out, and yet there was evidence that any tricky boy could see that the land had once been central to folklore.”