"The Most Forgettable Story in the World" (1971/1974)

- Jon Nelson

- Sep 17, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 18, 2025

Mountains delectable they now ascend, Where Shepherds be, which to them do commend Alluring things, and things that cautious are, Pilgrims are steady kept by faith and fear. — John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress (1678)

“By stumbling backwards over no road at all, down hill and through tangled brush, until we found ourselves in the bottom of a pit,” a dour old machine issued. “Then we noticed that the bottom of the pit was actually the top of the Delectable Mountain. If there is nothing lower, then also there is nothing higher. To be in the middle of a plain is the same as to be on the top of a mountain, if all the mountains are gone and forgotten. No, I don't believe that there are any roads, or have ever been. Why should there be roads to get to where we already are? And why should we leave when there is nowhere else to go? What need of roads?”

“The Most Forgettable Story in the World” is about a society so perfect that it has forgotten almost everything about itself, its setting a meeting with a theme, “The Insufficiency of Mere Perfection.” Nearly nobody shows up. The few humans and machines who do attend all suffer from lassitude. It doesn’t take them long to realize they can’t discuss the topic well because they share the same problem: collective amnesia. As one character puts it, it’s “a familiar syndrome, this worrying that there is something forgotten.”

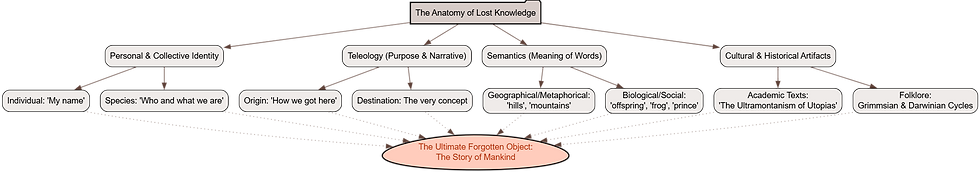

And it goes beyond forgetting small facts. They have forgotten the meaning of basic words like “hills,” “destination,” and “offspring.” Any understanding of who they are and whence they came? Gone. They try to piece together their history with old stories, and it only makes things more confusing.

One machine remembers a fairy tale where they were “princes turned into frogs” (The Fall). A young girl recalls a different story where they were “frogs turned into princes” (Evolution). But what does it matter? The problem is that no one here remembers what a prince or a frog even is.

A dour old machine offers another theory: there was no journey or purpose at all. He says they got here by accident, by “stumbling backwards over no road at all . . . until we found ourselves in the bottom of a pit.”

The story's ending doesn't bring any resolution. A young man says, “I remember what I have forgotten.” He now remembers that he is missing two things: “My destination and my name.” But when asked if he remembers what his name and destination are, he says, “Oh no, no. I merely remember that they are what I have forgotten.” So he hasn't remembered details, just the concept of having a name and a purpose.

To appreciate this one, I propose playing the “What are the best stories to introduce someone to Lafferty" game. As far as the Lafferty fan community goes, this game is all but done. A few years ago, The Best of R. A. Lafferty (2021) tried to play the game well and screwed it up by not tapping into the fan community. The commentary was often lazy and self-involved, and the selection as unimaginative as “Best Of” collections usually are. I don't need to point out that this game usually defaults to identifying the essentials, the ought-to-haves, the nice-to-haves, and so forth. What is an essential? Honking no-brainers. “Nine Hundred Grandmothers”? There are other ways to play the game.

So, a confession about "Nine Hundred Grandmothers." It’s not one of my favorites. I have ideas about it, including what the laughter is about, but I’m not sure the story even makes my top fifty. Of course, I see why "Nine Hundred Grandmothers" is considered one of Lafferty’s best and most memorable stories, and I see why he thought so himself. But if people asked me what to read to get to know Lafferty, they’d run up against my nasty case of not wanting to play the “Best of” version of the how-to-introduce-people-to-Lafferty game.

I mention all this because "The Most Forgettable Story in the World” may be the best example of another approach. It’s “best” not in the sense of "Nine Hundred Grandmothers." It’s best in the sense of being a shortcut to the RAL nerve center.

It programmatically explains much of what Lafferty is about, and so intensely concentrates his preoccupations that one could take any number of directions away from it and be less lost in the lesser known stories and novels. “Nine Hundred Grandmothers" won’t help you much, and may even mislead if you mistake what might look like absurdism.

Now contrast it with "The Most Forgettable Story in the World," where we encounter the problems of the large cast of characters, most of whom invite no emotional investment as character; of dialogue overriding action—or rather, of dialogue as intellectual action; and of resolution deferred or absent to put pressure on reader reception.

We see major themes and images pulled into synchronous orbit: amnesia; flatland and mountains; humans and machines in contrast with each other, and machines and humans in contrast with other humans and other machines; intergenerational disagreement; the felix culpa versus the phylogenetic tree; linguistic degradation as the coefficient of cultural decadence. Catholicism (Augustine) and Protestantism (the Delectable Mountain). One could go on.

It is a pitch perfect lesson on how amnesia works in Lafferty—amnesia as a double action, double eclipse: first, the onto-amnesia of the Fall, when man was cut off from preternatural graces; and second, the cultural amnesia attending world collapse.

Then there is the big one. This is the short story version of “The Day After the World Ended” and the story logic (in nuce) of In a Green Tree, the same attack, but not wearing its polite-company face. Instead, we see the vacant, stupidly amnesiac faces of those who must create a new world, the consequence of utopian achievement, and we are thereby in a better position to understand the essay and its summons:

"By every definition, this is Utopia. Of course some of us have always regarded Utopia as a calamity, but most of you have not. In its flexibility and in its wide-open opportunities, this is the total Utopia. Anything that you can conceive of, you can do in this non-world. Nothing can stop you except a total bankruptcy of creativity."

The story does all this in three pages.

If I were assembling the short stories into a super-anthology sequenced by theme, I would be inclined to place "The Most Forgettable Story in the World" first, as a kind of prelude. The choice would be programmatic rather than commercial. After all, the double meaning of the “The Most Forgettable Story in the World” is a joke about the second kind of thing.

Theme / Motif | “The Most Forgettable Story in the World” (1974) | “The Day After the World Ended” (1979) | Connection |

Forgetting & Amnesia | Characters obsess over what has been forgotten: roads, mountains, offspring, princes, and the concept of destination. | The essay stresses impenetrable amnesia after the end of Western/Modern Civilization—people can’t remember the old world clearly. | Both treat forgetting as the defining human condition: memory loss is the barrier to meaning. |

Search for Identity | A young man recalls only that what he has forgotten is his name and destination. | Cites Plato: man once defined as “a being in search of meaning,” but now man no longer searches. | Identity is tied to memory and purpose—without remembering, identity collapses. |

World Already Ended | Perfect world where everyone and everything has forgotten their origins, implying history/world is already gone. | Essay insists the world (Western Civilization) ended between 1912–1962; we are living in Flatland, post-catastrophe. | Both argue the “end of the world” has already happened, not some future event. |

Utopia as Ruin / Emptiness | Perfection is meaningless. Characters can’t define basic words, yet claim the world is “perfect.” | Present is a “Utopia” of total freedom, but nothing grows, the world is barren, uncreative. | Utopia is not fulfillment but stasis, sterility, or void. |

Metaphors of Roads / Paths | Machines and people wonder about roads that led to perfection, only to conclude there are none. | The essay describes us plowing a “field that isn’t there anymore” and wandering in ruins. | Both use path/road/field metaphors to convey disorientation and loss of trajectory. |

Collective Condition of Oblivion | Forgetting is universal: no one remembers “frog” or “prince” or even “destination”. | Amnesia is collective: destruction took away even recollection itself; “all the looking-glasses were broken”. | Shared insistence that this is not personal but universal amnesia. |

Question of Renewal | Hints of a forgotten story about mankind’s origin and destination. Lost but once known. | Toynbee’s “Phoenix Syndrome.” Civilizations reborn from ashes, the possibility of a new creation. | Both end by raising the question: can mankind remember or build again? |