"Junkyard Thoughts" (1983/1986)

- Jon Nelson

- Oct 31, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Nov 6, 2025

“But the fact is, Paul, that I write as clearly as I am able to. I sometimes tackle ideas and notions that are relatively complex, and it is very difficult to be sure that I am conveying them in the best way. Anyone who goes beyond cliché phrases and cliché ideas will have this trouble. It's a little bit like polarized glass. It's all clear enough looking out from my viewpoint; but it may be opaque from the other side to eyes different from mine. It can't always be helped, though.” — Lafferty, interview Paul Walker

“But you are the hypnotized ground bird, Drumhead, and I am the snake,” came the voice of J. Palmer Cass. “The ground bird never finds courage enough to shoot the snake. It just doesn't work that way. Why am I blue-eyed now, you wonder? Oh, it is only the contact lenses. It takes big ones though to blot out the big friendly brown eyes of Jack. I always take off his old hornrims with regret. That slight crack in the corner of the glass, that sloppy winding of small copper wire to hold the frame together. Who wouldn't trust a slob wearing such homely glasses? Who wouldn't trust him to be a slob forever? Those touches were sheer art. And ’twas myself, not Jack, who thought of it.”

“Ah, but you only beat me because I am not at my best today. I'm not really ever at my best any more. Junkyard, what are you doing? What is that blue horror that you're fumbling in your paws? What are you doing to your eyes?” “Putting in a set of those blue contact lenses that J. Palmer Cass wouldn't have been J. Palmer without. They've oversized contacts. They had to be oversized to cover the brown pupils of Jack Cass, and my own eyes are almost twins of Jack's. I want to see what the lenses do for my aura. What do they do for my aura, Drumhead?” “Gah, they turn me into a trembling ground bird, and you into a hypnotic snake. Take them out, Junkyard.”

Like “Camels and Dromedaries, Clem,” “Junkyard Thoughts” is a deep exploration of the schizo-gash. The story has dark wit and shows Lafferty being virtuoso in his off hours, working tonal tricks he perfected and that no one else replicates, which is say that it achieves its dissociative effect through the techniques he developed as a writer of radical originality. To me, it feels like the unpublished mystery-oriented stories from the pre-nucleation phase of 1958 to the early 1960s. It is what they might have looked like had Lafferty already developed his storytelling tools and thought the story might sell.

By 1983, the market situation was entirely different and unwelcome to him, so this also looks like Lafferty simply having fun with his craft, and it's one reason I enjoy it so much. Below, I’ll offer a brief plot summary, followed by my interpretation of what’s really happening, alongside a way to unify its dissociative logic. There are really only two characters in this one, and one doesn’t appear until the final page.

Our point-of-view consciousness for most of the story is detective Drumhead Joe Kress. He confronts Jack Cass, a pawnbroker and junkyard operator, in Cass’s pawn shop on Polder Street. Kress is investigating the disappearance of J. Palmer Cass, an elegant swindler whom he believes is Jack's cousin. Kress says he can almost feel the fugitive hidden nearby, "looking at me with those hard blue eyes of his, those snake eyes." Pawnbroker Jack is a genuine All-American Slob with a rough voice and gap-toothed grin and a checkbook with a jackass (Jack Cass) with a gap tooth under him. Jack flatly denies any family connection. When Jack steps out of the pawn shop, Kress searches the place, full of all kinds of clutter, a place that "always seems much larger on the inside than on the outside." He finds no physical trace of the fugitive.

The investigation continues over a game of chess played on an old nail keg between two valuable Queen Anne chairs. Kress gives the baffling details of J. Palmer's escape from the law a few hours ago. Palmer somehow slipped away from his townhouse. Men saw him go in. No one saw him go out. Kress says the man's powerful magnetism scared him, making him feel like a shivering ground bird before an elegant snake. As they play, Jack’s big dog, Junkyard, gives him valuable coaching, advising him on moves. Kress’s suspicion deepens when he recalls seeing the names Cass/Cass listed together in a police directory and, for the first time, notices a distinct physical resemblance between the two men: they both have a powerful "bull neck, and bull necks are hard to disguise."

Kress moves to arrest Jack, but Jack reacts with surprising, reflexive strength. He throws the captain across the room, then apologizes. Now held at gunpoint by Kress, Jack breaks down. He says his real name is John Palmerworm Cass. He was named for his father’s belief that the biblical palmerworm was "the devil inside me, the devil that was sometimes my other appearance." Then there is a change. Jack’s demeanor transforms. He becomes the cruel and articulate J. Palmer Cass. The new personality mocks Kress and gives some details about how he pulls it off: "Oh, it is only the contact lenses. It takes big ones, though, to blot out the big friendly brown eyes of Jack." This, along with a partial dental bridge and a blond hairpiece, lets him exist as two identities.

With the J. Palmer personality seizing control, Jack/Palmer leads Kress through a secret tunnel while the submerged Jack personality begs, "Shoot us, Drumhead!" All this happens through the same mouth. Then J. Palmer outlines a plan to force Kress into a suicidal public confession, calling him the "hypnotized ground bird." Lafferty uses a scene cut at the most dramatic moment, and the reader later learns that the dog Junkyard attacked the Cass creature, causing Kress to accidentally fire his revolver. The shot did not kill the body, but instead killed the Jack Cass personality, leaving only the J. Palmer alter, who was then captured by the authorities. This is what we are told, at least.

The story ends after all these events where the reader learns that Drumhead Joe Kress is currently a patient in the Bethlehem Institute for the Mentally Disturbed. His new reality consists of daily visits to the deserted pawn shop, where he hallucinates playing chess and conversing with his "'invisible dog,' as they call you." An attendant, representing objective reality, sees only Kress in an empty room with "neither Queen Anne chair nor chess board here, nor visible dog either." The story ends from within Kress's hallucination, as Junkyard, pleased about winning their game, warns that what Kress "had better worry about is his end game."

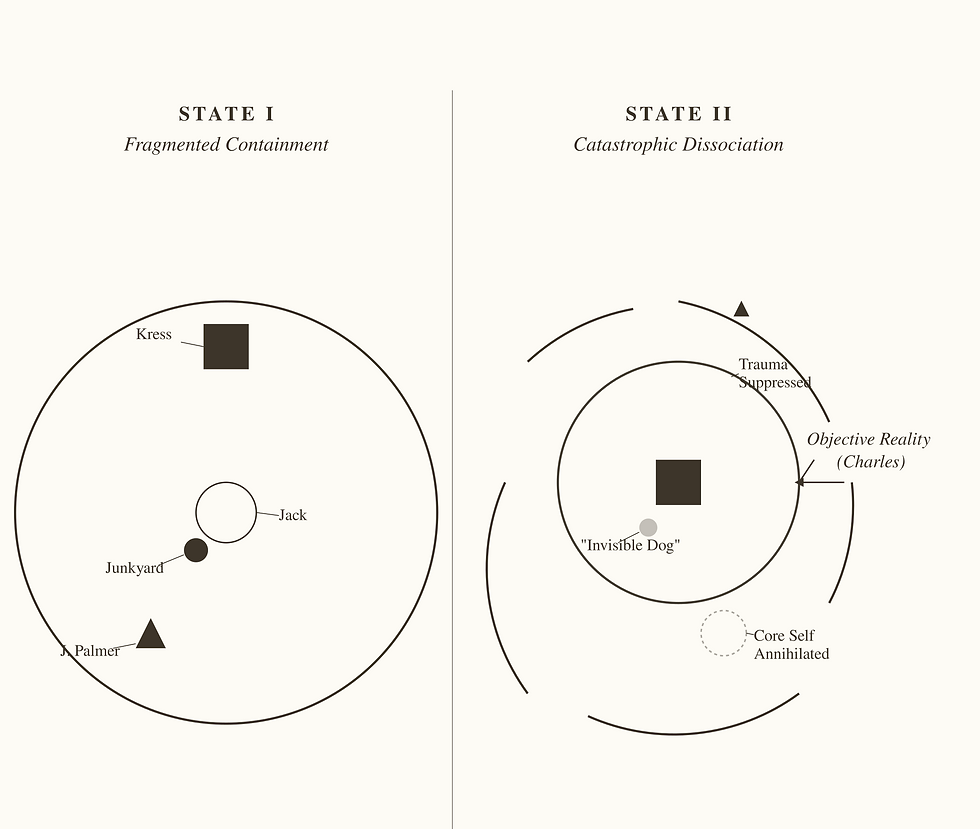

Obviously, this is a story about the four alters of one dissociated identity—or perhaps three, depending on how one understands Junkyard. Lafferty loved this story, as he told Dan Knight. The ambiguity here is around the blue contacts. On one hand, the contacts with the Kress-focalized version of the narrative support a purely rational, criminal interpretation of the events. J. Palmer Cass calls them a simple prop, just something to complete his disguise and blot out the "big friendly brown eyes of Jack," and the "hypnotic" power is just expert psychological manipulation.

On the other hand, there is the palmerworm aspect of the story, the spiritual corruption, and the story’s tie to the Book of Joel, where the contacts are a bit like the canker that cannot be avoided. They’re like instruments of dissociation at its most malevolent. The effect they have on the stablest of the alters is insane, and there is something genuinely terrifying about how Lafferty has Junkyard go from being savior to sadist on a dime.

I read Junkard at the end of the story to be a remanifestation of the palmerworm, which successive layers of devouring:

That which the palmerworm hath left hath the locust eaten; and that which the locust hath left hath the cankerworm eaten; and that which the cankerworm hath left hath the caterpiller eaten.— Joel 1:4

The ambiguity centers on the blue contacts, the story's image of the palmerworm’s appearance. In the Kress-focalized version of the narrative, these lenses are just things, one element in J. Palmer Cass's rational, criminal interpretation of events: "I might be insane, but there is method to my madness, and I am in control." J. Palmer Cass calls them just a prop, a practical element of disguise meant to obscure “the big friendly brown eyes of Jack.”

On the other hand lies the palmerworm aspect of the story, in which the blue contacts are like the plague animals of the Book of Joel in which four insects eat through everything, in the sequence of palmerworm, locust, cankerworm, and caterpillar. Here, the contacts are the recycling center of dissociation at its most malevolent, consumptive axis of the alters. By the end of the story, Jack Cass has been eaten by his own psyche, with Lafferty giving us something unforgettable in the portrayal of his dog Junkyard, who shifts from man’s best friend to a sadistic palmerworm in an instant, becoming a primary alter. Kress is up for consumption next.

Such is my reading of the story. Much of its brilliance comes from just having to read it on parallel tracks and arrive at a reading as one works out the dozens of uncanny moments Lafferty creates. An example to show how this works. On the unreliable narrator track, Kress is weirded out by “two men” speaking through one mouth, as in the following:

“Shoot us, Drumhead! Oh, do shoot us now!" the pleading Jack Cass personality begged from a corner of the complex mouth. "Pay him no mind, Captain," the J. Palmer Cass personality said from the center of the same mouth. "He’s a mawkish slob. The passage is this way."

On the panoramic track, a narratively induced dissociation is happening within the reading experience by way of Kress’s focalization, for the reader knows that “three men” are speaking through a single mouth, the “third man,” Kress, being no more aware he is in the mouth with the other two.