"Camels and Dromedaries, Clem" (1967)

- Jon Nelson

- Sep 19, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Oct 16, 2025

“Is there an anti-Christ — the man who fled naked from the garden at dusk leaving his garment behind? We know that both do not keep the garment at the moment of sundering.”

I’ve been thinking about “Camels and Dromedaries, Clem,” one of my favorite Lafferty stories. It is also one of his most philosophically demanding, though it doesn’t look like it. Daniel Otto Petersen has recently written about the story in an essay that considers it alongside Lafferty’s “Splinters.” It is fair to say that he and I find “Camels and Dromedaries, Clem” interesting for different reasons, but Petersen is right that making sense of what happens in the story would require a radically different metaphysics from onto-theology. He develops an interpretation that does exactly that, and his essay is well worth reading.

My view is that "Camels and Dromedaries, Clem" is best read as a thought experiment showing the risks of taking its animating premise seriously and trying to get around onto-theology. This becomes complicated by the fact that Lafferty is continually interested in the schizo-gash and believes that people are fundamentally split. For me, the answer is found in how Lafferty sees the human person as being created in a Trinitarian image but as being downstream of creation history. The human person experienced the Fall and is currently alienated in human history. As a consequence, I would argue that “Camels" is a metaphysical horror story that undermines its own premise and laughs at this repeatedly, most memorably when it shows us the image of Veronica's two graves.

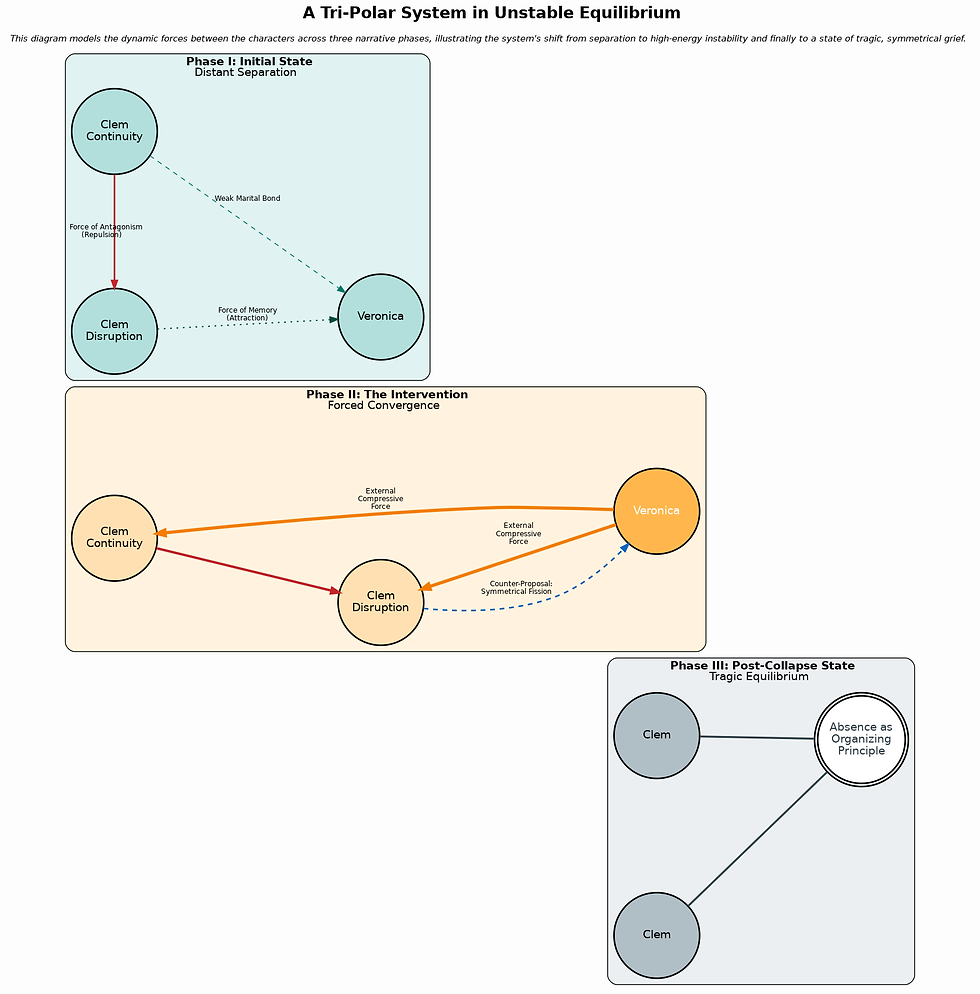

Briefly, the plot involves a successful traveling salesman named Clem Clendenning who splits into two near-identical individuals. After a phone call where he speaks to his own double, the "original" Clem (the nature of being an “original” is part of the story’s puzzle) flees into a solitary, compromised existence, taking up an “avocation of drinking and brooding and waiting” in places like the Two-Faced Bar and Grill. His double continues his life, career, and marriage to his wife, Veronica. Years later, when Veronica discovers the original Clem, she insists the two must reunite to become a whole person again, exasperatedly telling them, "You can't be jealous of each other. You're the same man." Toward the end of the story, the two Clems instead argue that the only logical solution is for Veronica herself to divide. "There is another way," one Clem says in a voice so sharp it scares them all. "Veronica, you’ve got to divide... You’ve got to come apart." This kills her. The story ends with the two Clems paying her a "special honor": "They set two headstones on her grave. One of them said 'Veronica.' And the other one said ‘Veronica.' She'd have liked that."

Much of what shapes my interpretation comes from how profoundly heretical the doubling and splitting off of Christ is. Lafferty, I think, gives us a strong hint that even entertaining such a possibility is precisely the wrong path. It’s one of his brilliant instances of the devil quoting scripture—when a man in a bar asks why Matthew’s Gospel has “two demoniacs” and “two blind men” when the others have only one, he whispers, “I think he was one of us”—and though I’m tempted to linger on how he does this, that would be a distraction. My goal here is different. To get at the philosophical core of the problem the story raises, the best guide I know is the extraordinary British philosopher Derek Parfit (1942–2017).

Parfit was one of the most important moral philosophers of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. He spent most of his career at All Souls College, Oxford, while also teaching at Harvard, NYU, and Rutgers. His major contributions centered on personal identity, rationality, and ethics, and he was especially influential in shaping how we think about future generations and moral responsibility. The book I believe sheds the most light on “Camels and Dromedaries, Clem” is his landmark Reasons and Persons (1984), a classic of analytic philosophy. In it, Parfit challenges conventional assumptions about identity and morality, arguing that personal identity is not what fundamentally matters. I disagree—and I think Lafferty’s story shows why he disagreed.

Helpful here are Parfit’s ideas about personal identity and branching. They can be summed up like this:

Aspect | Scenario A: Normal Survival (e.g., Waking up tomorrow) | Scenario B: Branching Survival (e.g., Clem's Division; a teleporter duplicates you but doesn't destroy the original) |

The Event | One person at Time 1 continues their existence as one person at Time 2. | One person at Time 1 has their body and psychology perfectly duplicated, resulting in two distinct successors at Time 2. |

Psychological Continuity (Relation R) | Holds in a one-to-one form. The person at T₂ is psychologically continuous with the person at T₁. | Holds in a one-to-many form. Both successors at T₂ are fully psychologically continuous with the person at T₁. The relation has branched. |

Personal Identity (PI) | Yes, it is preserved. Because Relation R holds uniquely (one-to-one), the conditions for personal identity are met. | No, it is not preserved. Identity is a logically unique, one-to-one relation. You cannot be identical to two different people. Since there is no non-arbitrary reason to say you are one successor and not the other, you are neither. |

The Outcome (Parfit's Conclusion) | You survive. What matters (Relation R) is preserved, and this preservation is properly called "Personal Identity." | You survive, but your Personal Identity is lost. What matters (Relation R) has been perfectly preserved and even duplicated. This is "survival without identity." |

Is it as good as Normal Survival? | This is the baseline for what we value in continuing to exist. | Yes, and possibly even better. It is not death. It is a "double success." To think this is as bad as death is to confuse having two successors with having zero successors (a confusion of 2 with 0). |

Analogy | A river continues to flow in a single channel. | A river splits into two equally full and powerful downstream branches. The original "River X" no longer exists, but all of its water continues to flow in the two new channels. |

If “Camels and Dromedaries, Clem” had been written by a devout and theologically informed Catholic author other than Lafferty, I suspect it would have taken a very different course. The central puzzle, on its face, like much of Lafferty’s work on the schizo-gash, runs so strongly against the Christian understanding of the human person that another author might have felt compelled to reinterpret the premise entirely. The story would then shift into another kind of philosophical investigation into the mechanics of identity, one with a constructive premise.

Why? The orthodox Catholic position is plain as glass. The human person is an integrated unity of body and a spiritual, immortal, and indivisible soul created directly by God (Catechism of the Catholic Church, §§362–366). A soul cannot be divided or duplicated. A Catholic author, bound by this teaching and encoding his beliefs, would have to explain the phenomenon of the two Clems in a way that is not a simple case of soul bifurcation. The story would no longer be a thought experiment attacking what we might call Reductionism.

To define a few terms here, personal identity is that which makes a person the same unique individual through the various changes the person experiences over a lifetime. Opposed to this is reductionism: the view that this identity is not a separate, deep fact (like a soul) but consists of physical and psychological continuities that are somehow necessary and sufficient to make someone what we call a person.

One can imagine an inferior version of the story where "other Clem" is not a human person but a malevolent being sent to tempt Clem into despair by questioning his God-given identity. The story would become one of spiritual warfare, where Clem must reject the illusion. Alternatively, there could be a science-fiction approach with a theological twist: science, in its hubris, has learned to replicate a body and brain, but not a soul. The other Clem would be a "philosophical zombie," biologically human but not an actual person. There would still be a Clem with a soul, the real Clem. This second version would be a cautionary tale about the limits of materialism, and Lafferty does this kind of thing in Past Master. Recall what the Programmed Persons claimed to have done to the corpses of the criminals and how they came to be Astrobe’s secret masters.

A third path would be to treat the split as just an allegory. One Clem would personify Clem's sinful nature, and the conflict would be internal, with the goal being repentance and the integration of the true self with God's will, rather than the physical merging of two bodies. Lafferty hints at this, but he doesn’t want the reader to go entirely in this direction. I think we can see that because the “original” and, arguably, lesser Clem is pretty damn sympathetic.

Element of the Story | Reductionist Version | Hypothetical Catholic Version |

The Central Conflict | What is the nature of personal identity when psychological continuity can branch? (A philosophical puzzle) | How does a person maintain faith and moral integrity when confronted with an evil that mimics his very self? (A spiritual crisis) |

The Nature of the "Double" | A genuine second person, a successful survivor who is also "Clem" in a meaningful way. | A spiritual imposter, a soulless replica, or a spiritual allegory of Clem's sinful nature. It is definitively not Clem. |

The Key Question | "'If he's me, who am I?'" | "Is this being a creature of God, or a deception from the Father of Lies?" |

The Character's Goal | To understand the new, bizarre reality and find a way to live a "compromised life." | To reject the double, reaffirm faith, save his soul, and seek redemption. |

The Role of Veronica | Represents the Non-Reductionist view, trying to restore a lost unity based on the mistaken belief that identity is what matters. She is the one who says, "'You act like you're only half a man, Clem.'" | She would likely be a source of spiritual strength or a victim of the demonic deception, whose faith and love are tested. |

The Thematic Resolution | A darkly comic acceptance of the new reality (survival without identity), culminating in the attempt to divide Veronica. | The triumph of faith over illusion, the damnation of Clem if he fails the test, or his redemption through suffering and repentance. The story would end with a clear moral and theological judgment. |

In short, a more conventional Catholic author could not write Lafferty's story because it looks so contrary to sacred doctrine. Such an author would probably take the same premise and use it to affirm the thing Lafferty and Parfit seek to deconstruct: the existence of a unique, unified, and metaphysically deep self, the soul. That is what I meant by constructive premise. The didacticism would be constructive instead of deconstructive.

What ends up happening is that Lafferty creates an Illustration of a position like Derek Parfit’s, especially when Parfit worked out his Reductionist arguments against the traditional view of personal identity. But because Lafferty was a devout Roman Catholic, the story is best read not as an endorsement of this view, but as a theological reductio ad absurdum, demonstrating the ontological consequences of a world without the unique, indivisible soul.

To try to show this, I'll set out the direct parallels between the narrative and Parfit’s philosophy, treating the story as a practical demonstration of Parfit's most challenging thought experiments.

Philosophical Axioms & Definitions

The Non-Reductionist View: Personal identity is a fact. A person is a unique, separately existing entity (e.g., a soul) whose existence is all-or-nothing.

The Reductionist View: The fact of a person’s identity is not a further fact, but consists in psychological continuity and connectedness (collectively, Relation R).

Parfit's Claim: Personal identity is not what matters for survival. What matters is Relation R. When Relation R branches, identity ceases, but survival continues.

The story fits this. Clem Clendenning’s split is a literal depiction of Relation R branching, creating a "Branch-Line Case" where the original Clem's life overlaps with his replica's. This leads to the phenomenon of survival without identity, which Lafferty presents as both amusing and terrifying. This is our intuitive but (for Parfit) irrational attachment to the uniqueness of our identity. As the two Clems diverge over time, their shared memories branch further, illustrating how psychological connectedness can weaken even while continuity remains. Their friend Joe Zabotsky observes, "There are some old things between us that he recalls and you don't; there are some that you recall and he doesn't; and dammit there are some you both recall, and they happened between myself and one man only, not between myself and two men." Finally, Clem's question, "If he's me, I wonder who I am?" would be, in Parfit's view, an empty one, as there is no further fact to discover about which one is the real Clem.

But this is shattered by the external fact of Lafferty’s Roman Catholicism, which brings in an overriding theological axiom: the person is a unity of body and an indivisible soul, guaranteeing a unique identity. (This is why I read Lafferty’s schizo-gash characters as depictions of human experience rather than as his actual beliefs about meeting, say, one’s fetch.) This axiom cannot be reconciled with the story’s events if they are read through a Parfitian approach. A Catholic author cannot, in good faith, present the division of a person as a two-souled metaphysical possibility. The story’s purpose is therefore not to illustrate such a possibility as real but to expose its horror by putting pressure on its materialist premises, which exposes how horrible they are.

Lafferty writes a story in which the Reductionist View is true, bracketing out the soul to explore the premise to its logical end. At the largest level this is a version of the Tritarian God without its divine simplicity. The result of this premise is a state of spiritual torment; Clem's “compromised life” is a form of damnation, and his discovery of a community of other "sundered persons" is a descent into a hell of fragmented beings. Secular reason, represented by the analyst who tells Clem he is suffering from a "tmema or diairetikos of an oddly named part of his psychic apparatus," offers a comically inadequate explanation for this terror. In contrast, Veronica's intuitive, Non-Reductionist demand to restore the "whole man" is Lafferty’s voice in the story: it is the voice of theological and moral sanity. The story's conclusion is the triumph of an absurd, soulless logic, as the two Clems inflict their own branched Relation-R experience upon Veronica. The final image of two headstones points up the absurdity.

So I would say that Petersen is right in one sense, though I wouldn’t use his philosophical tools to get at the issue. "Camels and Dromedaries, Clem" does not present a view compatible with Roman Catholicism, but it does present a world where Relation-R gets a hearing, which makes it susceptible to readings that settle with versions of Relation-R metaphysics.

That’s my reading of this tricky little story. It’s a dialogue between two irreconcilable worldviews, masterfully using the logic of one (of which Parfit's Reductionism is the most sophisticated version I know) to reveal the perceived spiritual necessity of the other (the Catholic doctrine of the soul). It’s an illustration of a philosophical theory and an argument against it.