"Other Side of the Moon" (1960)

- Jon Nelson

- Sep 15, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Sep 16, 2025

“I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it. If a count were taken, the score would be three billion plus two on the other side of the moon, and one plus God knows what on this side.” — Michael Collins, Carrying the Fire (1974)

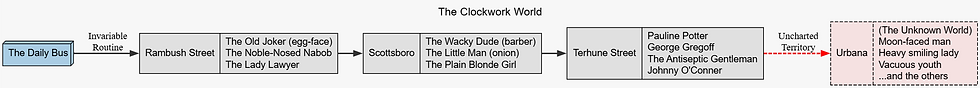

"Other Side of the Moon” is early Lafferty. It centers on Johnny O’Conner, who lives by routine. Every evening, he takes the same bus with the same passengers. They include the old joker with the egg-shaped face, the noble-nosed Nabob, the little man who looked like an onion. Each one gets off at the same stop, every time. One night, a fellow rider, a plain blonde girl, breaks the pattern. When it’s her stop, she says, “Not tonight.” That shakes Johnny, so he rides one stop farther than usual. After stopping by a different bar, he walks home. But things have changed. It’s like seeing his house for the first time, like seeing “the other side of the moon.” For instances, notices the cracked paint and the torn screen.

The next night, now in a reckless mood, he follows the girl again and ends up in the same strange place: the Krazy Kat Club Number Two. There, he overhears a barmaid telling a story about a woman who uses her husband’s fixed routine to cover up a secret life. The man, she says, is “so deep in a rut he can’t see over the top.” Then she says the woman’s name: Sheila O'Connor, Johnny’s wife. Johnny trembles. He spills his chaser. The life he thought was safe and ordinary is upended. He has left the rut.

This is one of the first Lafferty stories I read. I’m not sure why. I think I downloaded The Man Who Talled Tales, scrolled through it on my iPad, and picked this one because it was short. As one of his early stories, it follows a more conventional structure than his later work. But two things stand out to me now. First, it takes on a writerly problem Lafferty kept returning to: how to handle too many characters. Rather than avoiding the issue, the story builds a structure that can hold more characters than most writers would ever attempt in six pages.

Second, it has Lafferty themes that would grow more radical and experimental over time. The protagonist, Johnny O’Connor, discovers he is living two lives—one he’s aware of, and one he isn’t. This makes him one of Lafferty’s early versions of a “schizo-gash”—the split or doubling of identity—which Lafferty of course develops in characters like Finnegan, who lives an upper and lower life, and in countless others.

In this story, the gash shows up in the physical world, exteriorized, in the never-noticed-before cracked paint and torn screen of Johnny’s house. If Finnegan is an inverted schizo-gash, Johnny is an early, everted one. The reader sees Johnny being cleaved, as if becoming an early form of the Lafferty ghost—another variation on Lafferty’s statement that “the only thing that I have learned about all people, that they are ghostly and that they are sometimes split-off.”

What for Johnny amounts to alienation from objective conditions becomes ontologized in Finnegan and in other characters in Lafferty, as in the great passage in The Devil Is Dead, in which Finnegan sees it as clearly as he ever will:

“He remembered almost everything now, his upper life with its certain occupations and sets of friends, his lower life with other sets. He remembered the strange division in himself that was not new. But he did not remember anything about the last several months, and he sure did not remember what had happened last night. He went to his room to sleep.”

But Lafferty hasn’t arrived at the Ghost Story yet.

I love how clearly this early short story uses alcohol as a map of Johnny’s psychological escape from routine. It’s smart. I’ve never had a Vodka Collins, but it sounds like the perfect drink for someone stuck in a rut: safe, predictable, a mid-century standard that takes no thought, just a life running on autopilot.

The first time Johnny breaks that pattern, he orders a Cuba Libre, a drink that both Finnegan and, apparently, Lafferty himself liked. The name, “Free Cuba,” feels like a small, quiet toast to independence, a cautious act of rebellion. It is just exotic enough to free Johnny a bit, but still common enough not to push him too far. It captures his first, uncertain step into a larger world.

On the next night Johnny not only breaks his word to his wife, he also orders a sazerac. That’s a real departure. A sazerac is no bland highball but a complex, historic cocktail with mystique. He orders it just “to see what it was like.” Whenever I go to New Orleans, I always make sure to get one, and a gin fizz, but neither is a drink I’d order in my hometown. Too exotic, with its mixture of sugar, Peychaud’s bitters, rye whiskey, rinse of absinthe, all finished with a twist of lemon, all coming together in bracing, liquorice-tinged flavor.

By choosing the sazerac, Johnny reaches into the dangerously unknown. The drink is bitter, complex, and tied to a storied past, a New Orleans past full of booze and sex. Afterward, splashing vodka into tonic water isnt the same.