"Old Foot Forgot" (1968/1970)

- Jon Nelson

- Sep 16, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 17, 2025

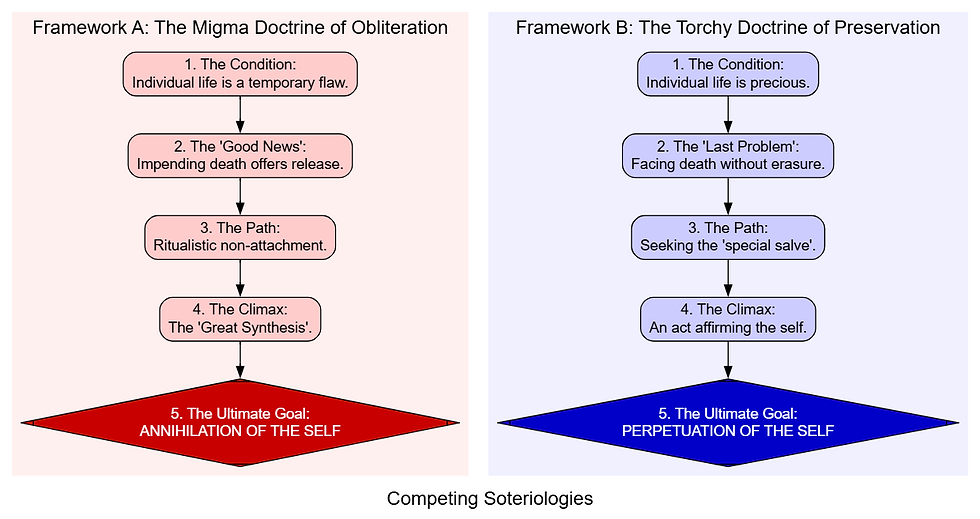

“Old Foot Forgot” is, like much of Lafferty’s work, a funny, strange, and poignant philosophical tale disguised as science fiction. Unlike yesterday’s “The Rod and the Ring,” however, it is highly approachable. It wrestles with a longing for personal identity after death, and with those who insist that the longing is misguided. In the West, this is Heraclitus instructing us that we dissolve into the cosmic Logos; Parmenides insisting that distinctions are illusions and only Being-as-One is real; Plotinus teaching that our highest destiny is absorption into the One, individuality transcended. It is Meister Eckhart’s call for the “little self” to die, the fana’ of the Sufi mystics, the system of Spinoza, and the half-mystical pessimism of Schopenhauer. Here, Lafferty takes aim at the fashionable spiritual syntheses of his time, filtered through writers like Aldous Huxley and Alan Watts, and given fresh cultural currency by the Beatles’ 1967 journey to India.

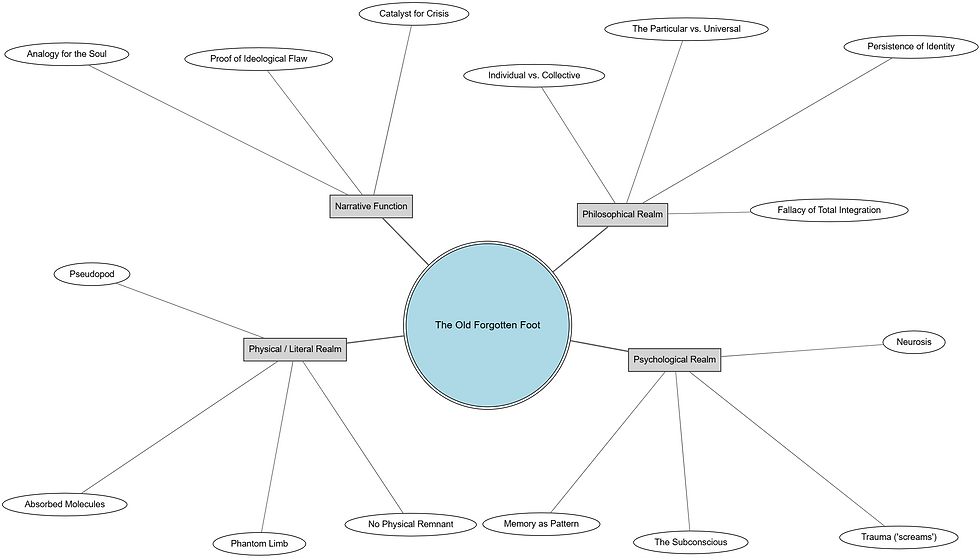

There are memorable characters in the story. The first is Dookh-Doctor Drague himself, our clinic-weaving protagonist. He receives his first "genuine spherical alien patient," a sphairikos named Krug Sixteen who suffers from an impossible ailment. Though the sphairikoi are "total and indiscriminate entities" who are "never ill," Krug is different. He is tormented by a phantom limb., a single pseudopod from his youth that, despite being long absorbed, now "screams and moans constantly." Is this just an exacerbated case of phantom limb syndrome?

This case distracts the Dookh-Doctor from his own "happy news": he is dying, a fate his culture celebrates as a joyful return to the "oneness that is greater than self." As Krug describes the pain of a forgotten part crying out for its identity, the Dookh-Doctor begins to see an analogy to his own impending dissolution.

As his death approaches, the Dookh-Doctor finds he lacks the proper attitude for his "great synthesis." Lay Priest Migma urges him to welcome becoming an indistinguishable part of the "great stuffiness," but Drague rebels against the blessed obliteration. He develops a "sneaky feeling that he would rather live than die," defiantly stating, "I want me to be me. I will refuse forever to surrender myself." The priest’s final argument, that a brief life is like a temporary pseudopod that shouldn't wish to be remembered, is what settles it. Seeing himself in Krug's lost foot, Drague flees, vowing, "I'll remember it a billion years for the billion who forget."

On his last night, after ritually burning his home, Drague runs through the dark to find the one hope Krug had mentioned: a specialist named Torchy Twelve, who possesses a "special form of the twinkling salve." He finds the hut and cries out his desire not for oblivion, but for a slumber that preserves his sense of self. He wants something to send him into a "kind and everlasting slumber," but with one crucial condition: "But I want it to be me who slumbers." The story concludes as the expert Torchy invites him in, promising, "This person, though promiscuous, is expert. I help you—"

The word promiscuous is an astonishing lexical choice on which to end this story, which begins with Luke 4:23—“Physician, heal thyself”—and ends with Matthew 11:28–30: “Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.”

Term | Language of Origin | Original Meaning | Significance | Text |

Dookh | Sanskrit/Pali (duḥkha/dukkha) | "Suffering," "pain," "unsatisfactoriness." | Drague is a "Dookh-Doctor," healer of spiritual suffering, directly linking the story’s conflict to the First Noble Truth. | “It is good for a Dookh-Doctor to have a different patient sometimes.” |

Sphairikos | Greek (sphaira / sphairikos) | Sphaira = "sphere"; sphairikos = "spherical." | The aliens are spheres, symbolizing wholeness and cosmic unity. | “The sphairikos rolled or pushed itself in… a large translucent rubbery ball of fleeting colors.” |

Nostos | Greek (nostos) | "Homecoming," "return." | Repurposed as a ritual of burning/renewal, signifying metaphysical return to oneness. | “This was all symbol of the great nostos, the returning.” |

Pseudopod | Greek (pseudo-pous) | "False foot." | Becomes metaphor for the individual self, transient yet suffering. | “It is one of my pseudopods… It protests, it cries, it wants to come back.” |

Moira | Greek (moira) | "Fate," "destiny." | Archetypal name of the lay sister who sets events into motion. | “Dookh-Doctor, it is a sphairikos patient,” Lay Sister Moira… |

Migma | Greek (migma) | "A mixture." | The lay priest’s name reflects doctrinal syncretism or blending into unity. | “So Lay Priest Migma P. T. de C. tried to inculcate the right attitude in him.” |

Drague | English (Allusion) | Hints at "drag" or "dragoon." | Suggests burden of mortality and coerced acceptance of death. | “The happy news about himself was that he was a dying man…” |

Arktos | Greek (arktos) | "Bear." | Name of alien “jokers” and disease Drague suffers from. | “He was dying of an arktos disease, one never fatal to the arktos themselves.” |

Speir-sky | Irish Gaelic (spéir) + Greek/Latin (sphaera) | Spéir = sky; sound suggests “sphere.” | Symbolizes circularity and cosmic oneness. | “He slept that renewal night under the speir-sky.” |

Quasi-Gaelic Terms (ull, piorra, innuin) | Irish Gaelic | Ull = apple; piorra = pear; innuin ~ onion. | Ground human culture in archaic, earthy language. | “He ate innuin or ull or piorra when they were in season.” |

Anātman / Anattā | Sanskrit/Pali | "No-self," "no permanent soul." | The sphairikoi doctrine: “There is no identity.” | “There is no identity. But this one cries to come back…” |

Samsāra | Sanskrit/Pali | "Cyclic existence," rebirth. | Mirrored in the endless pseudopod cycle. | “We push them out and we draw them back… millions of times.” |

Nirvāṇa | Sanskrit/Pali | "Extinguishing," "liberation." | Echoed in the ideal of “blessed obliteration,” which Drague rejects. | “Pray for blessed obliteration. I will not pray that I be happily lost forever.” |

Tanhā | Sanskrit/Pali | "Craving," "thirst," "attachment." | Forgotten foot’s bhava-tanhā drives its suffering. | “It protests, it cries… Oh, the shrieking!” |

Karuṇā | Sanskrit/Pali | "Compassion." | Embodied in Torchy Twelve’s solution, absent in dogma. | “I believe it will reach my forgotten foot… and send it into kind and everlasting slumber.” |

Upāya | Sanskrit/Pali | "Skillful means." | Torchy Twelve’s salve functions as compassionate expediency that eases fear—also resonant with a sacramental anointing that consoles the dying. | “Torchy Twelve… exudes the special stuff in abundance… solves and dissolves everything.” |

Torchy Twelve | English (symbolic: “torch” + apostolic “twelve”) | Torch = light/fire; twelve evokes apostolic fullness. | Catholic element: Torchy acts like a minister of mercy at the hour of death—her “special salve” parallels the Anointing of the Sick/Last Rites: an oil that consoles and confirms personal identity (against dissolving monism). The “torch” (light) and “twelve” (apostolicity) amplify Catholic resonance. | “Torchy Twelve, help me… the special salve that solves the last problem, and makes it know that it is always itself that is solved.” / “It will know that it is itself that slumbers, and that will be bearable.” |

Salve (wordplay) | Latin/English | Latin salve = “hail”; English salve = healing ointment. | Lafferty’s running “salve” motif carries Catholic overtones—think chrism/oil of the sick and even a punny echo of Salve Regina. Torchy’s special salve isn’t the sphairikoi’s dissolving goo; it’s a merciful anointing that steadies the self for death. | “We are covered with the twinkling salve; it is one-third of our bulk.” / “It is the old old salve, and it’s lost its twinkle.” |