"How They Gave It Back" (1968)

- Jon Nelson

- Sep 11, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 14, 2025

On my mind today is “How They Gave It Back,” partly because of our violent times, and partly because it's a response to the American crisis that began in the 1960s. Today, the Washington Post ran an article titled “America Enters a New Age of Political Violence.” Today, one will find similar pieces in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. In The Atlantic is Graeme Wood''s "Political Violence Could Devour Us All," where he writes,

In the past day, some have murmured that we are returning to the 1960s, and a norm of political assassinations. Martin Luther King and the Kennedy brothers then, Kirk now. The old joke about the ’60s is that if you claim to remember them, you were not actually there and were instead having another ’50s while the counterculture passed you by. The playwright Sam Shepard (who was definitely there) had what I take to be a clear and unromanticized memory of that time. “The reality of it to me was chaos, and the idealism didn’t mean anything,” he told an interviewer in 2000. He said it was an emotional drain he could not wait to escape. “I was on the tail of this tiger that was wagging itself all over the place and was spitting blood in all directions.”

This is the mental climate of “How They Gave It Back,” with its implicit judgment: Who would want it?

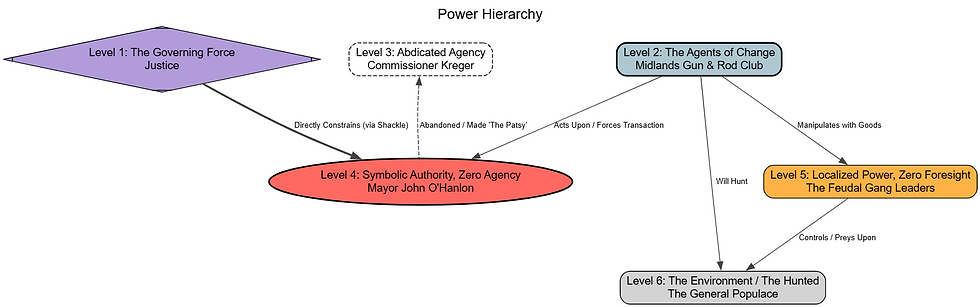

The story follows Mayor John, whose full name is Giuseppe Juan Schlome O’Hanlon, of Big Island (Manhattan). He was once a dignified leader, but now he is broken and irrational. He shrills and keens and moans, chained to his desk by law, unable to leave until he can sell what is left of Manhattan. The city has become a wasteland of gangs and violence. There are “people unburied in the streets, people knifed down hourly, people crazy and empty-eyed or glitter-eyed.” The shackles will release Mayor John only if a buyer meets the requirement of “Fair Value.”

His chance comes when three Indian officials from the Midlands Gun and Rod Club arrive, offering hatchets and blunderbusses and more in trade. The exchange is accepted as the island’s “Original Value from Original Entailment,” and John is freed. Then he is shot. The new owners turn the island into a most dangerous game-style hunting preserve.

This is a grim story, told with grim wit. It is a long way from yesterday’s “The Doggone Highly Scientific Door.” Irony is everywhere, and the satirical boundaries are destabilizing. Some edge-case ambiguity complicates how we are meant to interpret the story’s moral shape. For example, how are we supposed to evaluate the three Indians—a petroleum geologist, an electronics engineer, and a lawyer—and the funny murder of Mayor John? This is the angry moral humor one finds in Jonathan Swift. "Last week I saw a woman flayed, and you will hardly believe how much it altered her appearance for the worse."

I'll list some ideas from the story that stand out to me.

Colonialism and reparations. By having the island sold back for its original price (the material equivalent of sixty Dutch guilders), Lafferty takes an axe to the idea that restorative justice is simple. As the buyers’ lawyer puts it, “the island has reverted. It’s really worthless . . . Perhaps its reverted value is now its original value.” The story mocks both the initial colonial deal—treated here as a kind of unpaid debt now settled with “Fifty hatchets,” “Twenty guns,” and “One brass frying-pan”—and the belief that historical theft can be neatly undone. Lafferty seems to be saying that true justice is elusive, especially once violence and greed are involved. As two tentacles of Ultimate Justice itself conclude, when one asks about the original twenty-four dollars, the other replies, “No, no . . . That was only the estimated value placed on the material. There was no specie paid.”

Then there’s the question of urban governance and optimism. Mayor John himself is a satire of several left-liberal ideologies. Born into a political family, he “was given the names to please as many groups as possible.” He’s an idealistic reformer trapped in an impossible situation, a figure for real-world urban leaders facing crises they can’t solve. Lafferty also targets what we now call identity politics (a term coined in 1977). John’s multi-ethnic identity and popular rhetoric—calling himself “man of the people” and his election a “high triumph”—are undercut by the anarchy of Big Island. Even his former commissioner calls him “the ultimate patsy” for trying to govern it. This is consistent with the larger pattern of Lafferty’s work: political idealism and structural rot are connected.

And what has been rotted out? Well, it's law, equity, and civilization itself. "How They Gave It Back" is withering here. The only law left is a literal-minded cosmic mechanism that enforces form over substance: the “psychic-coded lock” governed by the “Equity Factor.” On one level, this is the idea that the letter kills but the spirit gives life. On another, it resembles Sittlichkeit, an idea that has left an impression on me. It is the lived actuality of freedom within ethical life. Sittlichkeit is more than duty: it is the unity of subjective will and objective institutions. That unity has collapsed on Big Island. The trap mechanism that pins Mayor John is satisfied once the deal is done: “He had disposed of the island in equity. He had gotten Fair Value for it, or Value Justified, or at least Original Value from Original Entailment. And it sufficed.” The universal of Ultimate Justice has become removed from life, disincarnational, and monstrous.

Finally, there is violence and human nature. This is Lafferty holding up a mirror to human brutality. I’ve written about the bloodsmell in his work, how it can be sacramental. But here it is debased. Joyless mayhem, or counterfeit joy, or mirthless mirth. I am not sure what to call it, but we see it too much in our culture now.

As one gang leader says, seeing the blunderbusses, “They spark them off, and it’s wonderful. Cuts people right in two.” The hunters quote Hemingway: “‘There is no sport equal to the hunting of an armed man.’ Ah, we’ll hunt them here.” Beneath the wit, Lafferty is saying something brutal about real tendencies.

The murder of Mayor John:

Mayor John was free. He started to run from the room, fell down on his crippled leg, and arose and ran once more. And was caught in a blunderbuss blast. And then the great hunt began. The three members of the Midlands Gun and Rod Club had most sophisticated weapons. They were canny and smooth. This was the dangerous big-game hunt they had always dreamed of. And their prey were armed and wild and truculent and joyous. It would be good.

It's not.