"Endangered Species" (1973/1974)

- Jon Nelson

- Nov 2, 2025

- 5 min read

These animals on our coming up to them stared at us and remained quiet where they stand, not knowing whether they had wings to fly away or legs to run off, and suffering us to approach them as close as we pleased. Amongst these birds were those which in India they call Dod-aersen (being a kind of very big goose); these birds are unable to fly, and instead of wings, they merely have a few small pins, yet they can run very swiftly. We drove them together into one place in such a manner that we could catch them with our hands, and when we held one of them by its leg, and that upon this it made a great noise, the others all on a sudden came running as fast as they could to its assistance, and by which they were caught and made prisoners also. — Saar, Johann Jacob, Volkert Evertsz, and Albrecht Herport. Account of Three Notable Voyages to the East Indies. Amsterdam: Jan Rieuwertsz and Pieter Arentsz, 1671.

“Good for the female,” Agata exclaimed with a sick smile. “Of course it's a little hard to worry about the Spokelspuk's being endangered. It really should be extirpated, a thing that laughs like that? We have this special rescue and revival job to do, though, and we will do it. We are professionals.”

Given Lafferty’s creationism and stories like “Animal Fair,” he can look contradictory on environmental issues. He was politically conservative, yet deeply loved the beauty of what he saw as God’s creation. “Endangered Species” is a story I’m especially fond of, one that approaches the topic obliquely by mocking those who arrogate authority. Is it fair? No, it isn't fair, which is its greatest defect. George Meredith put it like this: “The laughter of satire is a blow in the back or the face."

On the other hand, it is more fair than it might seem. What Lafferty makes fun of here is captured well by the complexity of the issues involved. As I read it, he isn’t disputing that species die out, or that this matters. Anyone who reads him long enough recognizes his preoccupation with such questions. Yet I have no doubt he disliked the shibboleth “endangered species,” along with the fact that its chief advocates were allied with a view of biology he fundamentally opposed.

The idea of there being endangered species became common coin in Lafferty’s lifetime. It entered public discussion in conservation writings in the 1940s and the 1950s, but its roots go back to the 18th century. In the 18th and 19th centuries, naturalists like Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) discovered that species could disappear forever. This was a challenge to the idea that creatures were fixed and eternal. And, of course, the industrial age and colonial expansion underscored the devastating effects of overhunting and habitat loss. From this grew early conservation actions, including the establishment of national parks, wildlife protection laws, and organizations like the Audubon Society.

When Lafferty was a young adult, the idea of endangered species became formalized through science and law. A big moment in this history was the founding in 1948 of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It developed global systems for assessing species’ risk of extinction. They were later codified in the IUCN Red List. In the United States, the Endangered Species Act of 1973 created strong legal protection. Lafferty finished his story in February of 1973. Nixon signed the Endangered Species Act into law on December 28. Lafferty’s story has a good time making fun of all the seriousness in the national discussion at the time.

At the top of the power pyramid in “Endangered Species” is Director Benoni Lambert of the Species Conservation Bureau. He has learned of the endangered Spokelspuk, though we later learn he does not know what one is, and he assigns his top agents, the husband-and-wife team of Conrad and Agata Scampo, to a new project: saving the endangered Spokelspuk. Although Conrad and Agata are experts in their field, neither has ever heard of the species. To save face, they pretend to know and accept the assignment. They will investigate the nature of the Spokelspuk. Director Lambert lets them hear a recording of the male Spokelspuk’s sound, as if it were a birdcall, a disturbing laugh that unnerves them both.

The Scampos start by consulting specialists. They go to an ornithologist, who confirms that the Spokelspuk is not a bird. Next, they go to an entomologist, who says that it is not an insect. Throughout their search, they are followed by a persistent, pink-haired medium named Madam Hexe. She says that they need her assistance and that she is the only one who can help them with their assignment, but Agata repeatedly dismisses her. Madam Hexe continues to follow them, absolutely certain that they will eventually require her services.

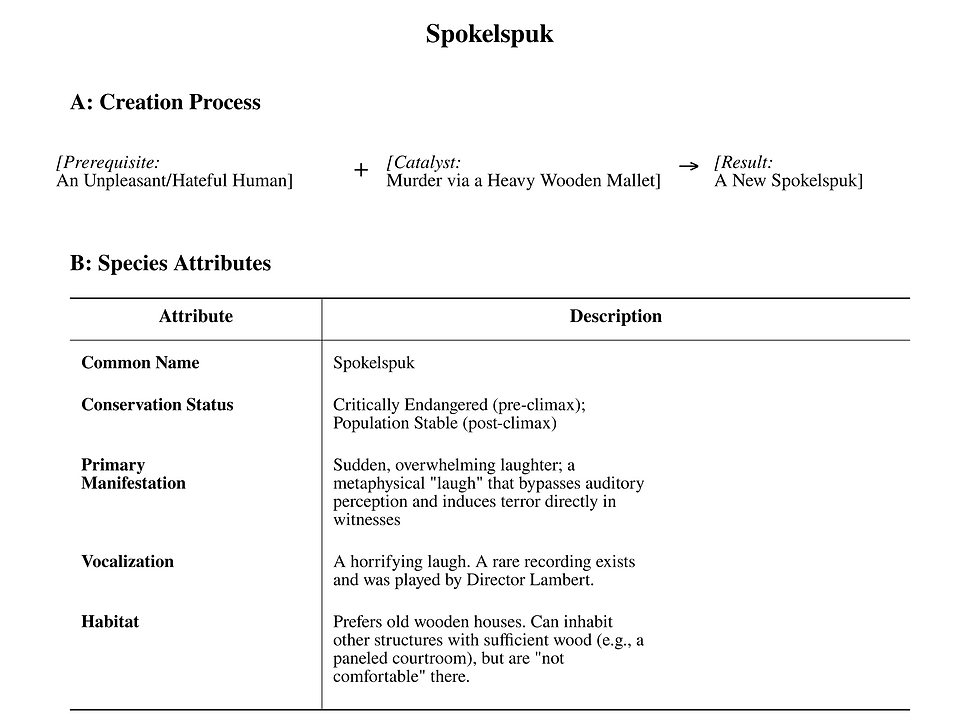

It is from Madam Hexe that we learn the truth about the species. A Spokelspuk is not an animal but a type of ghost. It’s created when an unpleasant or angry person is killed with a heavy wooden mallet. The species is endangered because fewer people fit the criteria to become one. She directs the Scampos to an old, haunted house at 1313 East Hodges. It’s haunted by a small population of three Spokelspuks. Shortly after, Director Lambert contacts the Scampos and, having received new information, also tells them to go to the same address.

Conrad, Agata, and Madam Hexe arrive at the haunted house. Inside, they hear the chilling laughter of the two male Spokelspuks, followed by the even more terrible laugh of the female. The cacophony drives Agata into a state of fury. Seeing that Agata is "ready," Madam Hexe gestures to Conrad, who has become bewitched by Madam Hexe. Conrad picks up the wooden mallet that Madam Hexe brought and strikes Agata on the head, killing her. Immediately, a fourth laugh—Agata's—blasts through the house. The Spokelspuk population has increased by one.

The final scene takes place in a courtroom where Conrad is on trial for murder. He tries to explain the supernatural events, but the court considers him insane. Throughout the proceedings, the laughter of the Agata-Spokelspuk fills the room. Conrad asks to be executed with the mallet from the evidence box so he can become a Spokelspuk himself. As he speaks, Madam Hexe steps forward. She takes the mallet, and brains Conrad in front of the entire court. The entire scene is madcap physical comedy, with Conrad’s laugh eventually being heard. Madam Hexe tells the judge that the Spokelspuk is no longer endangered, hypnotizing him and giving him the suggestion that he could declare on this, before leaving the courtroom.

The Scampos are loathsome; their name, drawn from slang meaning “to rob on the highway,” more than hints at how Lafferty viewed certain appropriations made in the name of endangered species. It is a minor story, but an excellent one, with Lafferty contrasting the sterile, bureaucratic language of conservation against the black comedy and supernatural absurdity of manufacturing ghosts. He skewers apparatchiks more concerned with avoiding the admission of ignorance than with the essence of their work. There is sharp wordplay—“head count” drifting into murder—and delightful screwball humor around the taxonomy of ghosts.

“Yes, this is the same sort of thing,” Lambert spoke sadly. “Both the Spassenspuk and the Spottelspuk have been falsely identified as the Spokelspuk.” “I can see why, Ben.”

It is literal slapstick as the batacchio becomes the oversized wooden mallet of retribution familiar from Looney Tunes and Tom and Jerry. By the story’s end, Lafferty has made his point: under people like the Scampos, preservation will eclipse prudence, competence, and morality.