"Configuration of the North Shore" (1967/1969) and the Oceanic Novels

- Jon Nelson

- Aug 31, 2025

- 2 min read

Updated: Sep 7, 2025

In my understanding of how Lafferty’s fiction fits together, I group his otherwise uncategorizable genre novels under the term "Oceanic Novels," adapting one of Lafferty's terms. They play with the idea of transcending history to explore the exteriorized unconscious—here encompassing both the psychological unconscious and what Fredric Jameson called the political unconscious. The novels are ocreanic because the low mimetic cannot carry the eschatological intensity that Lafferty wants to explore. Genre work opened a line of flight. There’s an uncharitable reading of his artistic trajectory that sees him moving from a vision of contributing chapters to the American novel and other relatively low mimetic experiments to channeling the bulk of his creative energy into compensatory fantasies and satires. That’s not my view, but I can see how a case could be made.

What I recently referred to as the Big Egg Problem attempts to specify the writerly challenge Lafferty faced in transitioning from the low mimetic to the anagogical. It occurred to me that one of his finest short stories stages the dynamic. It begins in dissatisfaction with the low mimetic and its tendency to flatten the representational possibilities of fiction. The story is “Configuration of the North Shore,” collected in the most recent Centipede Press volume and among Lafferty’s best. It’s an X-ray of the Big Egg Problem: how does one arrive at transcendence in fictional form?

The story follows John Miller, a man haunted for decades by recurring dreams of a mysterious place called the North Shore, and Robert Rousse, the analyst who agrees to help him explore them. In a note on the story, Lafferty explained that it was based on a series of dreams he had experienced going back to his wartime service.

“This story had its origin in a series of watery dreams, some times delightful, sometimes dire and dangerous, that I had when I was a soldier in the South Pacific during World War Two. Each of them was a sort of quest dream, and each of them contained part of the vision of the North Shore. To get to the North Shore it self I’d have to die, and I was unwill ing to do this. And I didn’t want to lose the rich dream con tent either.”

Each dream in “Configuration of the North Shore” transpires in ritual stages: first, a grounding “Earth Basic” scene; then, a symbolic precursor dream; and finally, the central quest—across oceans, islands, and guardians—toward the elusive shore that always lies just beyond reach.

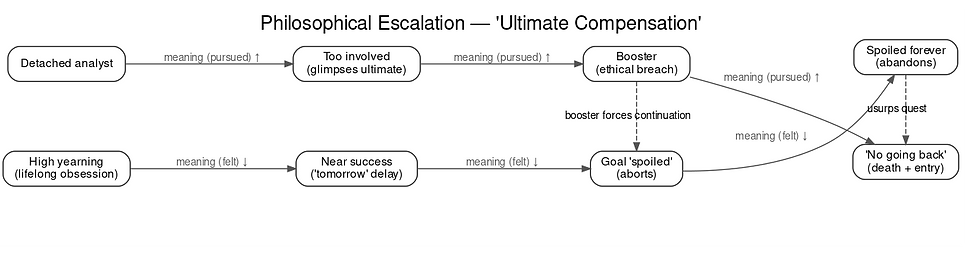

As Rousse records Miller’s sessions, he becomes increasingly entangled through a kind of metaphysical countertransference, first encouraging, then prolonging the dreams using psychological technology via his booth. This backfires, collapsing Miller’s vision into the banality of his own city (the stickiness of the low mimetic) and leaving him enraged, convinced the dream has been spoiled forever. But Rousse, now obsessed, undertakes the journey himself, following the oceanic logic through the watery abyss, past the emperor penguin, the leviathan, and the monokeros, until he crosses the final stele marked “Which None May Read and Return” and enters the North Shore, a place of transcendence from which there is no return.