"And Some In Velvet Gowns" (1974/1984)

- Jon Nelson

- Sep 12, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 14, 2025

“But my sin was this, that I looked for pleasure, beauty, and truth not in Him but in myself and His other creatures, and the search led me instead to pain, confusion, and error.”— St. Augustine, Confessions

Hark, hark! the dogs do bark, The beggars are coming to town. Some in rags, and some in jags, And some in velvet gowns.

“And Some In Velvet Gowns” is exospheric, as high-concept as Lafferty gets, but its height comes from somewhere. That can be misleading, though, because its most obvious bloodline runs through Jack Finney’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1955), Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters (1951), and Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” (1938)—all part of the Capgras-syndrome branch of science fiction and fantasy. That’s undoubtedly the generic line of consanguinity, but it won’t make the story easier.

So let’s try something big, a wider family that includes changelings, gods going in disguise, and all of Lafferty’s own fetches. It gets us closer because the story has ancient roots in spiritual infestation. Yes, this is one of Lafferty’s Gadarene swine songs, closer to St. Anthony in the desert than to The Thing's research station in Antarctica.

Why is pretty simple. This is allegory about sin, specifically about how venial sins, left unrecognized, dull the soul’s capacity for charity and leave it open to graver ones, until what remains is the hollowed person (ST I–II, q.88). Not that the story preaches. Not at all.

Perhaps the closest analogue I know—one that shows how personhood can be erased yet leave behind a terrifying trace—is didactic too, and it comes from a writer utterly unlike Lafferty, though born the same year: William S. Burroughs. It’s his “The Man Who Taught His Asshole To Talk,” also about identity invasion. That classic Bourroughs routine ends with the lines, "For a while you could see the silent, helpless suffering of the brain behind the eyes, then finally the brain must have died, because the eyes went out, and there was no more feeling in them than a crab’s eyes on the end of a stalk."

I find Lafferty's Elmer to be even more sinister:

“I will take you over, Fulgence,” the alien Elmer Fairfoot said.“You are the closest thing to an intelligent one in your group, and I in mine. We will be in accord. And I'll listen to you, down under there where you'll be, quite often. Maybe as much as a half minute a day.”

Oh, get off it, you go too far, someone might say. This is a light alien invasion story about aliens with space paint. That won't wash. The story makes little sense unless it is read as a severe allegory about sin, just as Burroughs’s routine makes little sense unless it is read as a savage allegory about how the unthought in language can ruin us. That’s also why I think "And Some In Velvet Gowns" would probably leave genre readers confused or cold if they aren’t attuned to Lafferty's approach to religious allegory.

Perhaps it is worth pointing out that Lafferty has his own version of Burroughs’s routine. It appears in Past Master (1968), where even there it is bound up with sin and privation.

“No. I am winning easily on Astrobe,” Ouden said. I have my own creatures going for me. Your own mind and its imagery weakens; it is myself putting out the flame. Every dull thing you do, every cliché you utter, you come closer to me. Every lie you tell, I win. But it is in the tired lies you tell that I win most toweringly.”

Note that the diminution of self in each Lafferty case is connected to the nature of being and goodness. Ens et bonum convertuntur. Whatever exists is good insofar as it exists, and goodness and being are thus inseparable, though conceptually distinct. Of course, goodness isn’t on the William S. Burroughs menu, and I read his allegory as perhaps saying something unintentional about his own artistic narcissism.

Why does this matter? Because Lafferty’s horror does not reduce the human subject to a physical trace, as body-snatcher plots and grotesque satires do, but exposes the terror of spiritual displacement—a science-fictional figure for a theological reality.

The story transpires in a courtroom. Judge Daniel Doomdaily presides over the hearing of six aliens, shackled and accused of plotting a takeover of the town. The aliens are masters of illusion, disrupting the proceedings with tricks and slippery claims. They appear chained; their number changes, but doesn't seem to change because of their paint. They themselves have no substance. As Doomdaily prosecutes them (with the help of six attesting citizens and two aides), members of the human side are summoned one by one to a vesting room. Each returns altered, and the line between human and alien is reconfigured. In the final scene, the judge himself is transformed. The takeover is complete. The hearing, it turns out, is only a formality, a public ritual for the victors.

I’m tempted to extrapolate more than I will, but I'll stay close to the more approachable allegorical elements.

First, the story squares with Catholic teachings on the nature of sin. Initially, the aliens are thought to be “nice folks.” They’re admired; as one citizen, Sam Joplin, admits, “They look like humans until you really look at them. And they’re such nice folks!” On closer look, their “gaudy clothes” are revealed to cover an “abomination.” Lafferty isn’t being subtle. The judge himself points out their deception: “All they have is gaudy clothes to cover their abomination.” This could not be more traditional: sin appears attractive on the surface; that is its disguise. “Satan himself masquerades as an angel of light” (2 Corinthians 11:14). Or, as Shakespeare put it, “a goodly apple rotten at the heart.” Lafferty takes the body-snatcher plot and makes it theological: evil gets invited not because of its horror but because of its meretricious charm. As Thelma Brightbrass admits, when her husband was replaced, he became wittier. She “never had so much fun in my life, for about a week.”

This is also a story about bodies, and a second central theme is the contrast between false embodiment and incarnation. The aliens themselves admit that their physical forms are illusory. Their lack of substance becomes a refrain. They use paint to simulate everything from chains to clothing. Elmer Fairfoot says, “I’m not wearing shoes . . . I just have my feet painted to look like it.”

A digression on the name Elmer Fairfoot before returning to the matter of bodies. A common device in Lafferty's fiction is the etymological name game, in which one part of a character's name holds a crucial clue while the other serves as flavorful misdirection. Here, Elmer is the flavor element, Fairfoot informational, an allusion to one of the best-known New Testament quotations of the Old. Isaiah 52:7 gives the image of a messenger racing across the mountains, his feet called beautiful because they carry the news of God’s deliverance, peace, and reign to a weary people.

St. Paul takes this and, in Romans 10:15, applies it to the gospel, saying that the true good news is Christ’s victory over sin and death, now proclaimed to all nations:

“How beautiful are the feet of those who preach the gospel of peace, Who bring glad tidings of good things!”

For both Isaiah and Paul, the attention is on the joy and necessity of the messenger: without someone sent to announce God’s salvation, the people cannot hear or believe, but when the message comes, it remakes despair into hope and exile into restoration.

Lafferty has Elmer Fairfoot, his messenger, travesty just this:

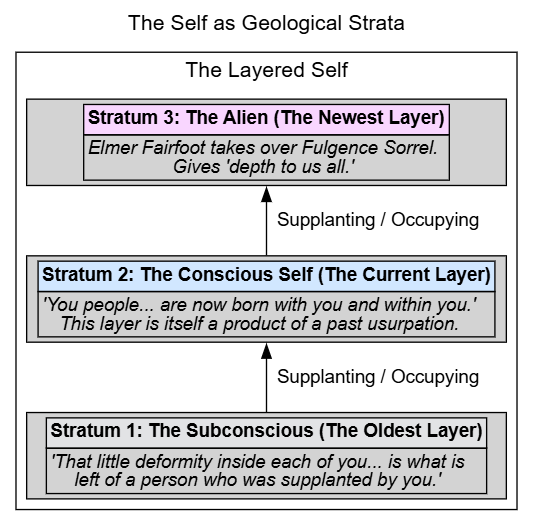

“Why should you want to avoid it?” Elmer asked. “Why do you object? These migrations are common. You’ve taken over yourself. That little deformity inside each of you, that person whom you sometimes call your subconscious, is what is left of a person who was supplanted by you. He is the one who, looking at it one way, had title to your body before you did.”

Just as Elmer voices the parasite’s logic of displacement, Augustine articulates from within what it feels like when the enemy claims the will itself.

“The enemy held my will, and of it he had made a chain and bound me. For out of a perverse will came lust, and the service of lust ended in habit, and habit, not resisted, became necessity. By these links, as it were, forged together (which is why I called it a chain) a harsh slavery held me fast. But that new will which had begun in me, freely to worship you and to enjoy you, O God, my only certain joy, was not yet able to overcome my former ingrained willfulness. Thus my two wills—the old and the new, the carnal and the spiritual—were in conflict with one another, and their discord robbed my soul of all concentration.” (Conf. VIII.5.10)

Both Lafferty and Augustine depict an intensely spiritual claustrophobia.

Returning to bodies, Bridget Upjones sits on a fairground scale and weighs “nothing, not anything at all.” When directly confronted about their bodies, the alien Delphina explains the alienating nature and the alien need for human hosts:

“Bodies.” "Aren't those bodies that you have there?” "Not good ones. They haven't any substance. We had to leave substance behind the way we traveled.”

It seems almost silly to point out something as obvious as the weight Christianity places on the mystery of the Incarnation, in which Christ took on flesh, uniting body and soul perfectly and substantially. But some readers will miss this dimension of the story. The aliens invert Incarnation. They are spirit-like beings that seem to incarnate but actually create subtractions of humanity. Lafferty sets up a situation in which the counterfeit embodiment of the aliens cannot help but draw a contrast, in the Catholic mind, with sacramental anthropology, which affirms the body as real, meaningful, and good.

We also have a ton of judgment imagery, particularly through the character of Judge Doomdaily, who presides over a courtroom filled with thunderous condemnation. Even his name is a parody of the Dies Irae. He thinks he is going to expose false appearances, calling witnesses, and naming the corruption before him. He confidently bellows, “Look at them! Look at them!” Then he himself gets absorbed by the evil he tries to condemn. He is easily deceived, becoming confused by the very illusions he seeks to condemn: “In chains? I never ordered any chains . . . Where did they come from?”

This is just traditional Christian allegory: human judgment, without the aid of divine grace, is inadequate. When Doomdaily is summoned to the “vesting room,” and when he comes back, he is one of them, saying, “But now we can function again.” The reader knows his faculties of judgment have been destroyed. Human authority cannot defeat evil on this level; only one Judge has that power.

Finally, "And Some In Velvet Gowns" is an apocalypse, an event that affects every town, but it’s not one of Lafferty’s explosive apocalypses. It's a sleeping sickness. It arrives through complacency and lapses of vigilance. It’s like the alien Delphina’s voice, which to an “analytical ear, would have sounded horribly unhuman,” but to a “sleepy and inattentive ear . . . sounded delightfully young-woman human.”

Some readers will see this as just a story about aliens who use alien paint. But it is, pretty clearly, an allegory. Does it work? I'm not sure. I’ve emphasized its treatment of sin. It’s a little more than that. If it works, it works best as an allegory about Catholic anxieties about sin. These include worries about discernment in seeing through its glamour; the challenges of understanding human embodiment, which rejects false flesh in favor of the sarx of the Incarnation; the fallibility of human judgment when it acts without grace; and the apocalyptic danger of surrendering to evil when vigilance fails.

I really do wonder whether this one throws off many non-Christian Lafferty fans.