Where Have You Been, Sandaliotis? (1977)

- Jon Nelson

- Mar 10, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Nov 18, 2025

The ethos of this blog is something in Lafferty’s Serpent’s Egg (1987). It’s something he has characters say about mysteries, my favorite genre:

"The trouble with mysteries is that the mystery-giver doesn't play fair," Inneall complained. "He doesn't give us all the clues." "Yes he does, Inneall. He gives all the clues."

That might be my favorite moment in Lafferty's work.

Although he experimented with mysteries, his great detective novel is Where Have You Been, Sandaliotis?, one half of Apocalypses (1977). It’s a book made entirely of strange turns, and throughout, Lafferty plays a game with the reader unlike anything else in his work. This is a matter of degree. He’s relentless, scattering contradictions and concocting so many seemingly throwaway details that it can feel like he’s inventing wildly in an onslaught of manic exposition, without bothering to keep track. But he is keeping track. Repeatedly, he draws the reader’s attention to contradictions long after most will have moved on. It’s these weird reminders that make Sandaliotis so different from anything else I have read.

Has anyone cracked how this book works? I haven’t seen it. It isn't discussed much. But I have a crazy theory, one that I haven't let go of after rereading it.

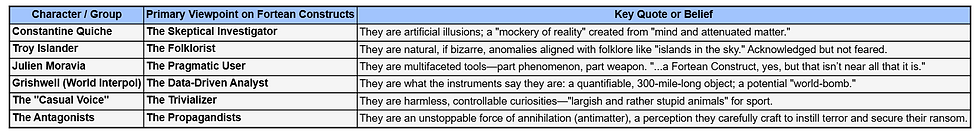

Constantine Quiche in Hell

I think the book hints that Constantine Quiche is a Frenchman, a former foot policeman with the last name Chataigneraie, and that he is in hell, having died the night before the novel begins. The other agents in Sandaliotis are quite likely devils tormenting him, and his handler, Grishwell, is part of the plan.

Lafferty provides an essential piece of insetting in the first chapter:

"Through the night, [Constantine] was interrupted only once, not into wakefulness, but into a dream. The rock pile seemed to have become an under-ocean rock pile, a grotto, a cave, a booming tidal cavern. A female dolphin visited him there with her springy fish-flesh and her cool ways. She smooched him in that slurpy way that female dolphins have, and there was an underwater echo to it. Then he felt the needle stabs that are so often a part of those strange-species kisses . . .We live in caves under the ocean and we have a dog that lives in the sky. Sometimes we come up. We whistle to our dog and we both gambol. If you hear anything else of us, do not believe it. This is all that we do. Will you not come and see me in my cave sometime, after this little ritualistic action that we are engaged in now is finished with? But the best detective in the world is always receiving various sorts of communications."

The dolphin in the dream will be associated with Aemilia Lilac, an enemy agent who gives Constantine the Judas kiss several times, the Judas kiss being a recurrent motif in Lafferty’s work. She later warns Constantine:

"Oh yes, I am of dolphin flesh, and quite a few other fleshes. Are you not finding that out with your investigations? But look out for us when we come up out of the ocean and whistle for our sky dog. We can blow you out like candles then."

By the end of the novel, the reader will have enough evidence to see that the agents are quite likely another set of Lafferty’s devils. Constantine gets a glimpse of what’s really happening:

"These creatures (the odds teetered between their being human or unhuman) came through as calculatingly insane destroyers. The whole thing showed the unfocused destructiveness and the mad irresponsibility, and the absolutely direct aim at a staked-out and self-immobilized target—Earth."

The Dungeons of Tertullian and Hell as Spectacle

Some of the strongest evidence that Constantine is in hell is the centrality of the Dungeons of Tertullian in the book.

Tertullian (c. 155–c. 220 AD) is a complex and uncomfortable figure in the history of Catholic thought. While not a Church Father, he was an ecclesiastical writer of significant influence. Near the end of the second century, around 197 AD, he converted to Catholicism and later became a priest.

However, sometime after 206 AD, he broke communion with the Church, embracing Montanism—an apocalyptic movement that anticipated Christ’s imminent return. (As a side note, his association with apocalyptic thought is one reason why Where Have You Been, Sandaliotis? is in a volume called Apocalypses.) Though Tertullian died outside the Church around 220 AD, some of his followers found their way back, largely through the efforts of St. Augustine (354–430 AD) nearly two centuries later.

In De Spectaculis (written c. 200 AD), Tertullian condemns the bloodlust of pagan audiences, warning that those who revel in such brutal entertainments will one day become part of an eternal spectacle of suffering. He envisions rulers, philosophers, and entertainers groaning in hell, forced to witness one another’s torments and endure the very cruelties they once relished.

Meanwhile, the saints in heaven are granted the privilege of witnessing this suffering. On this, he writes:

"But what a spectacle is that fast-approaching advent of our Lord, now owned by all, now highly exalted, now a triumphant One! What that exultation of the angelic hosts! What the glory of the rising saints! What the kingdom of the just thereafter! What the city New Jerusalem! Yes, and there are other sights: that last day of judgment, with its everlasting issues; that day unlooked for by the nations, the theme of their derision, when the world hoary with age, and all its many products, shall be consumed in one great flame! How vast a spectacle then bursts upon the eye! What there excites my admiration? What my derision? Which sight gives me joy? Which rouses me to exultation?—as I see so many illustrious monarchs, whose reception into the heavens was publicly announced, groaning now in the lowest darkness with great Jove himself, and those, too, who bore witness of their exultation; governors of provinces, too, who persecuted the Christian name, in fires more fierce than those with which in the days of their pride they raged against the followers of Christ. What world’s wise men besides, the very philosophers, in fact, who taught their followers that God had no concern in ought that is sublunary, and were wont to assure them that either they had no souls, or that they would never return to the bodies which at death they had left, now covered with shame before the poor deluded ones, as one fire consumes them! Poets also, trembling not before the judgment-seat of Rhadamanthus or Minos, but of the unexpected Christ! I shall have a better opportunity then of hearing the tragedians, louder-voiced in their own calamity; of viewing the play-actors, much more 'dissolute' in the dissolving flame; of looking upon the charioteer, all glowing in his chariot of fire; of beholding the wrestlers, not in their gymnasia, but tossing in the fiery billows; unless even then I shall not care to attend to such ministers of sin, in my eager wish rather to fix a gaze insatiable on those whose fury vented itself against the Lord."

In Sandaliotis, the director of the Dungeons of Tertullian puts it like this:

"When, for instance, I show thirteen men in the agony of death on the walls of the thirteen-sided room, I give the people something to feel important about; for they play at being God, looking through the God’s-eye of the panoramic camera in the ceiling of the room. There is the need of something to abuse, something to feel superior to, something to hate. All these things are satisfied by the writhing creatures stretched out on the dank walls where they babble out their brains in rambling words as they die. All my dramas are very therapeutic."

Lafferty’s detective novel is a Chestertonian nightmare built on Tertullian’s ideas, where suffering is staged, filmed, and consumed as entertainment. On one hand, there is the nightmare, which is not satire; on the other, there is the satire of Tertullian and the media. The Dungeons of Tertullian makes Sandaliotis an exceptionally dark sequel to Not to Mention Camels (1976), another of Lafferty’s critiques of media. It is perhaps unsurprising that the director in Sandaliotis and the protagonist of Not to Mention Camels each have unusual eyes:

“And his eyes appear like two glass eyes, even though they are moving enough and merry enough.”

“The eyes of this pan-morphic (he had jeweled eyes or cracked-glass eyes) established the field of battle and made it conform to their own vision.”

The Final Descent

Grishwell, Constantine’s handler, tells him early on to buy a parachute. By the end, readers have the internal evidence to understand why. The Director has already described his filmmaking process:

"What I do is create and direct psychological thrillers with a heavy historic and folklore underlay. I am very good at this. I try to do these pictures as cheaply as possible: how cheap I can do them is one measure of how good I am in this business."

And at the climax, Constantine finds himself inside the thriller, parachuting into what seems to be salvation:

"He tugged the lines to carry himself away from that central vortex. He refused to descend deep, deep below into the lilac depths of the ocean. There was the churning, hammering shoal water that would break up a ship or a man. And what else? Mighty steep odds against it. Oh, there was a little bit of solidity out there, about big enough to stand on. But it was a way, a chancy break-neck way where one might stay alive and sometime get to clear water or to help. If only—And the odds against it weren’t as steep as they had seemed at first. None of that hundred-to-one stuff. The odds were no more than ten to one against it now. 'Just one chance,' Constantine said. 'Just one way. Oh, Director, you said that you liked to cut it close. Director, you should be down here. This is really going to be close. You said that you wouldn’t have it any other way. I would, but I haven’t.'"

If I am right, Constantine Quiche hasn’t escaped from anything. He has plunged deeper into hell. And the show goes on.

Current notes:

Part of Lafferty's inspiration for Sandaliotis was Charles Fort's New Lands, 1923.

Part 1: Charles Fort's Core Arguments About Mirages

Fort | Explanation |

Rejection of Conventional Explanations | Fort accepts that simple mirages of known, nearby objects exist. However, he dismisses explanations that require a mirage to be projected thousands of miles with perfect clarity (e.g., Bristol, England appearing in Alaska). He considers such explanations scientifically absurd and designed to dismiss anomalous data. |

The Crucial Evidence of Repetition | The most significant feature of these phenomena for Fort is their repetition in a specific local sky. He argues that for a mirage of a distant city to appear repeatedly over the same spot on a rapidly moving Earth is a statistical and physical impossibility. This repetition is a central pillar of his argument. |

Implication of a Stationary Source | Because these mirages repeat in the same location, Fort concludes that their source must be stationary relative to that spot on Earth's surface. This leads him to two radical conclusions: 1) The source is an unknown object, world, or "New Land" suspended in the sky nearby, and 2) The Earth itself must be stationary. |

The "New Lands" Hypothesis | Fort proposes that these are not mirages of terrestrial locations at all. They are either direct, distorted views, reflections, or shadows of unknown lands and objects existing in the space relatively close to Earth. These are the "New Lands" of the book's title, part of an "extra-geography." |

Critique of Scientific Dogma | Fort uses the flimsy and often contradictory explanations for mirages to attack what he sees as the blind dogma of conventional science. He argues that science, particularly astronomy, ignores or invents absurdities to protect its core tenets (like a moving Earth and vast, empty space) rather than genuinely investigating strange phenomena. |

Part 2: Mirages mentioned by Charles Fort

Category / Example | Date(s) & Location(s) | Description of Mirage | Conventional Explanation | Fort's Interpretation & Critique |

REPEATING PHANTOM CITIES | ||||

Youghal Mirages | Oct 1796, Mar 1797, Jun 1801 <br> Youghal, Ireland (p. 77, 98) | Mirages of a walled town seen on two occasions. Later, an "unknown city" with mansions, shrubbery, palings, and forests was seen for over an hour. | Implied to be a standard atmospheric mirage. | The repetition in the same local sky is key evidence against a conventional explanation and points to a fixed, local source. |

The Alaskan "Silent City" | Yearly, June 21 - July 10 <br> Over a glacier near Mt. Fairweather, Alaska (p. 166-168) | A "phantom city" seen repeatedly. Described as having "plainly houses, well-defined streets, and trees," with spires and buildings resembling "ancient mosques or cathedrals." Likened to an "ancient European City." | A mirage of Bristol, England. This was influenced by the "Willoughby photograph," a likely hoax photo of Bristol. | Fort's primary example of scientific absurdity. He finds it ludicrous that a mirage could so perfectly and repeatedly pick out Bristol to project onto a specific screen in Alaska. He considers this proof of an unknown, stationary aerial source. |

THE SWEDISH MIRAGE SERIES (1881-1888) | ||||

Rugenwalde, Pomerania | Oct 10, 1881 (p. 124) | A village with snow-covered roofs, hanging icicles, and visible human forms. | Identified as a mirage of Nexo, Bornholm (100 miles away). | The first in a series that suggests a single, complex source rather than multiple, random terrestrial reflections. |

Lake Orsa, Sweden | May 1882 (p. 125) | Representations of steamships, followed by "islands covered with vegetation." | Not specified. | Part of the ongoing series; the complexity of the scenes is notable. |

Various Swedish Locations | 1883 - 1885 (p. 125) | A succession of complex, changing scenes: mountains, lakes, farms (Finsbo); a large town with a castle (Lindsberg); a town with warships (Gothland). | Not specified. | Fort interprets this series as originating from a single, large, temporarily suspended object or landmass over the Baltic/Sweden, from which various distorted views were seen. |

Valla, Sweden | Sep 12 & 29, 1885 (p. 125) | Described as cloud-forms morphing into monitors, a spouting whale, a crocodile, forests, dancers, and a park with paths. | Described as a "remarkable mirage." | The fantastical and morphing nature of the images strains the idea of a simple reflection of a terrestrial scene. |

Merexull, Russia | Oct 8, 1888 (p. 125) | A mirage of a city that lasted for an hour. | Identified with St. Petersburg (200 miles away). | Another example of a long-distance projection that Fort finds improbable, fitting into the larger pattern of the series. |

PHANTOM ARMIES & PROCESSIONS | ||||

Havarah Park, England | Oct 8, 1812 (p. 78) | "Phantom soldiers" seen in the sky. | Explained by meteorologists as aurora borealis; by physicists as mirages of distant troops. | Fort uses this as an early example of a recurring theme that defies simple explanation. |

Souter Fell, Scotland | June 23, 1744 (p. 103) | 27 witnesses saw troops of aerial soldiers marching over a mountain for two hours. | Sir David Brewster's theory: a mirage of secretly maneuvering British troops. | Fort ridicules this explanation as highly impractical and illogical, questioning how such maneuvers could be kept secret. |

Ujest, Silesia | 1785 (p. 103) | Mirage of General von Cosel's funeral procession. Appeared again several days after the actual procession had disbanded. | A mirage of the funeral. | The reappearance after the source was gone is used by Fort to demonstrate the absurdity of the conventional theory. He jokes, "...so may a shadow...see some of his shadows still wandering around without him." |

Montana, USA | Jan 17, 1892 (p. 138) | A "battle in the sky" showing Indians and hunters alternately charging and retreating. | A mirage. | Fort uses the detailed, dramatic content to question the simplicity of the mirage explanation and hint at actual events in an "extra-geographic" realm. |

OTHER AERIAL CITIES & SCENES | ||||

Liverpool, England | Sep 27, 1846 (p. 104) | A city in the sky. | Said to be a mirage of Edinburgh, suggested by a panorama of Edinburgh on exhibition in Liverpool at the time. | Fort points out the power of suggestion in shaping conventional explanations. |

Near Bone, Algeria | Summer 1847 (p. 104) | A "vast and beautiful city, adorned with monuments, domes, and steeples" that resembled no known city. | Not specified. | An example of an aerial city that cannot be traced to any terrestrial source. |

Vienne, France | May 3, 1848 (p. 104) | A city and an army in the sky, accompanied by "vast lions." Seen by 20 witnesses for two hours. | Not specified. | Fort emphasizes that the presence of lions is enough to "discourage any Brewster" and his simple mirage theories. |

Ashland, Ohio | March 12, 1890 (p. 137) | A representation of a large, unknown city. | Supposed to be a mirage of Mansfield (30 miles away) or Sandusky (60 miles away). The "more superstitious" called it the New Jerusalem. | Fort notes how interpretations are always framed in local or familiar terms, whether terrestrial cities or religious visions, obscuring the truly unknown nature of the source. |

--

The director quotes one of Horace's ode (4.7) to Constantine. Here is Horace's poem in its entirety, with lines relevant to Sandaliotis bolded:

The snow is fled: the trees their leaves put on,

The fields their green:

Earth owns the change, and rivers lessening run

Their banks between.

Naked the Nymphs and Graces in the meads

The dance essay:

“No 'scaping death” proclaims the year, that speeds

This sweet spring day.

Frosts yield to zephyrs; Summer drives out Spring,

To vanish, when

Rich Autumn sheds his fruits; round wheels the ring,—

Winter again!

Yet the swift moons repair Heaven's detriment:

We, soon as thrust

Where good Aeneas, Tullus, Ancus went,

What are we? dust.

Can Hope assure you one more day to live

From powers above?

You rescue from your heir whate'er you give

The self you love.

When life is o'er, and Minos has rehearsed

The grand last doom,

Not birth, nor eloquence, nor worth, shall burst

Torquatus' tomb.

Not Dian's self can chaste Hippolytus

To life recall,

Nor Theseus free his loved Pirithous

From Lethe's thrall.