Some Thoughts about "Through Other Eyes"

- Jon Nelson

- 4 hours ago

- 7 min read

Updated: 16 minutes ago

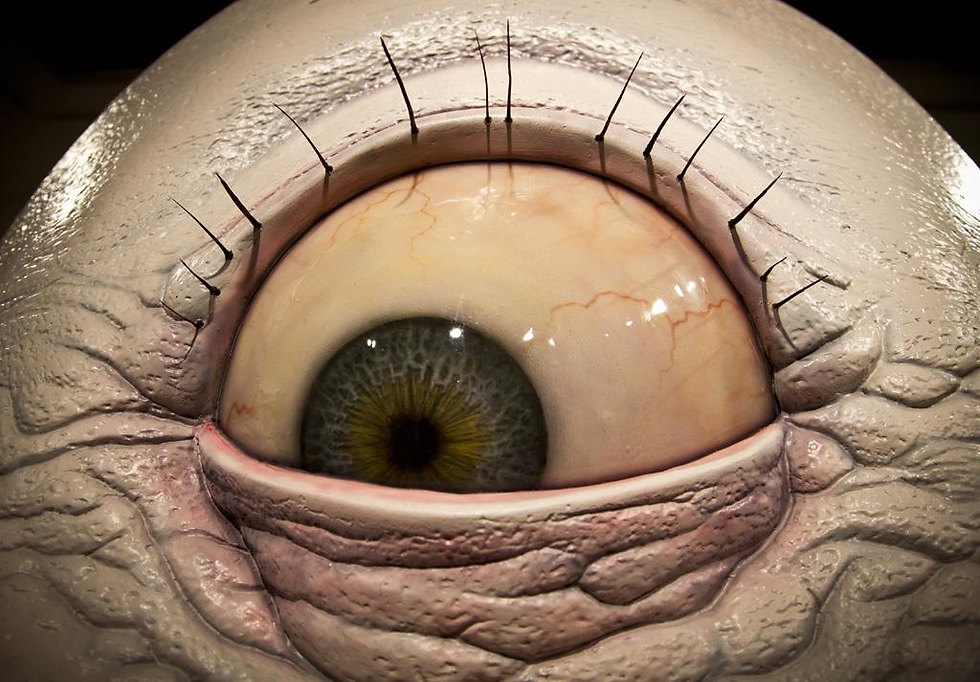

“I become a transparent Eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God. The name of the nearest friend sounds then foreign and accidental: to be brothers, to be acquaintances—master or servant, is then a trifle and a disturbance.”— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature

The attempt to see into the world of Karl Kleber was almost a total failure. The story is told of the behaviorist who would study the chimpanzee. He put the curious animal in a room alone and locked the door on it; then went to the keyhole to spy; the keyhole was completely occupied by the brown eyeball of the animal spying back at him. Something of the sort happened here. Though Karl Kleber was unaware of the experiment, yet the seeing was in both directions. Kleber was studying Cogsworth in those moments by some quirk of circumstance. And even when Cogsworth was able to see( with the eyes of Kleber, yet it was himself he was seeing.

That is one of my favorite passages in Lafferty. Karl Kleber, the peeping-tom psychologist, prompts Charles Cogsworth to have a moment of moral reflection. One assumes that Lafferty took the view that most psychologists were peepers.

Today I read a well written online essay on Lafferty’s “Through Other Eyes” that does a lot of essayistic hand holding, which is understandable on substack. It connects defamiliarization in Lafferty to Chesterton’s reception of the famous Mooreeffoc anecdote, which Chesterton took from a biography of Dickens and then included in his own work. The book is one of Chesterton’s masterpieces, though I recommend its evil twin, George Orwell’s favorite biography of Dickens, the one by the brilliantly bitchy Hugh Kingsmill who writes against the foaming Toby Jug.

The argumentative content of the substack piece amounts to saying that Mooreeffoc may have been a form of defamiliarization that reached Lafferty through Chesterton and is a textbook example of it. I would bet my bottom dollar on Lafferty having read the Dickens bio, a book I love. That is interesting enough. Its author concludes with the following:

“Lafferty pushes Chesterton’s principle to its limit, showing that sudden, total understanding of another consciousness may be psychologically shattering rather than ennobling.”

My problem with essays like this is pretty basic. There just isn’t enough thought. Do we want other-minds-could-break-us to be our takeaway of “Through Other Eyes”? Is it even the main point being made in “Through Other Eyes”? Cognitive shattering certainly happens, but where does the ennobling come from? Charles Cogsworth is just trying to solve his gavagai paranoia (“What if I am a girl to everyone but me?”), so he invents his peeper tech. He is not trying to ennoble himself, nor does ennoblement have anything to do with the aims of the story. The essay both situates Lafferty as a Christian and extracts his incisors. We get rehash of sf publishing history.

It set me thinking about something significant that gets overlooked in readings of “Through Other Eyes”: how Charles’s unethical arrogation of transparent access to other individual subjectivities usurps God’s authority. As part of his Cerebral Scanner experiment, Charles is willing to lie to his friends and acquaintances to acquire their brain data. His arrogation is perverse. In the first Institute story, Charles really is a dirty peeper, but the temptation is to read Charles through what comes later, the rest of the Institute cycle. The story warns against what we might call new forms of technologically mediated empathy and misused personal data.

While Valery Mok and Charles Cogsworth ultimately marry in the Institute cycle of stories, in “Through Other Eyes,” Charles’s overreach gets in the way of his shot at flawed and limited human love. Lafferty could have left it there. Once Charles sees Valery through the scanner, he can no longer see her through his own affectionate eyes and only makes his way back to a somewhat restored perspective by seeing her through Gregory Smirnov’s eyes. When Charles sees Valery as a beauty at the beginning of the story, Lafferty is in one of his rare moments of limited third-person, here because he is going to scrutinize the problem of perspective. Technique meets theme. As the story concludes, Lafferty warns against the mechanical attempt to bypass the mystery of other persons:

“Misunderstandings can be agreeable. But there is something shattering about sudden perfect understanding.”

Other readers tend to see the story as saying that people are different and that empathy is good. We have our private worlds. Qualia seem to exist. I would say, sure, true enough. But what about the criticism Lafferty is leveling about the invasion of privacy and graded access to the disclosure of Prime in its sacramental disclosiveness? We see how much this repulses him in stories like “Sex and Sorcery” and “The Casey Machine,” in the invasion of privacy on Astrobe, in peeping in on the Willoughbys, in the blackmail of Duffy, and so forth. There are many instances of this trespassing on the human person in Lafferty. Charles himself realizes the degradation inherent in his technical peering:

“I am looking through the eyes of a peeper,” he said. “And yet, what am I myself?”

As for being shattered by divine-only knowledge, one could point to “In the Turpentine Trees.” It, too, is a theme Lafferty revisits throughout his work. All this made me want to work out some adequacy conditions that seem to be implied in “Through Other Eyes,” since they play out in his later work. This mainly interests me because the story draws a distinction between ontological adequacy and perspectival relativity, and I think one reason the story has been so popular for a wide range of Lafferty readers is that readers tend to conflate the two. It is perfectly compatible for Lafferty to endorse his kind of semi-radical perspectivalism while still thinking that there is some way the World is, even if there are many words. Note how Smirnov’s perspective is special because it touches the "bones" of reality:

“The old bones of them stand out for him as they do not for me, and he knows the water in their veins . . . I am looking through the inspired and almost divine eyes of a giant, and I am looking at a world that has not yet grown tired.”

The billions of possible worlds in “Through Other Eyes” are not what I would call Prime in Lafferty’s work, the baseline reality grounded in his Catholic metaphysics. If that is right, then there should be a way to spell out the adequacy conditions. I have called the kind of worlds in “Through Other Eyes” versions of World 7 in Lafferty. Lafferty's Grolier history of the world set, which I have recently posted about documented Worlds 3. Astrobe in Past Master is a World 6. Fourth Mansions is a conspiracy fantasy that imagines an eschatological leap from World 2 to World 6 by bypassing World 4. Green Tree begins in World 2 and ends in World 4, unless we include its fifth part, an abandoned fragment, that would have taken us into a World 6 where mountains suddenly appear.

A perspective is inadequate when it fails to see the life inherent in the Prime, as Valery tells Charles:

“I saw the world the way you see it. I saw it with a dead man's eyes. You don't even know that the grass is alive. You think it's only grass.”

In thinking through this, I came up with the following idea of ordering adequacy in "Through Other Eyes" along three dimensions: intensity of vital disclosure (V₁), scope of vital disclosure (V₂), and tolerability (T). It is agent-relative, varying with who is perceiving, i. e., my eyes or your eyes. No human being can maximize all three, because if they could, they would be God. The closest one can get to that is Ralph Waldo Emerson fantasizing about being a transparent eyeball.

As everyone knows, the story peaks with Valery's intensity:

“She has a keen awareness of reality and of the grotesqueness that is its main mark. You yourself do not have this deeply; and when you encounter it in its full strength, it shocks you . . . There is a filthiness in every color and sound and shape and smell and feel.”

Let’s be frank. Valery did not agree to this. Charles has done the epistemological equivalent of rifling her lingerie. He has read her diary. He is a pig.

Euler peaks scope:

“It is the interconnection vision of all the details. It appalls. It isn't an easy world even to look at. Great Mother of Ulcers! How does he stand it? Yet I see that he loves every tangled detail, the more tangled the better.”

Neither of these is bearable to ordinary persons, which is one reason that I think Lafferty made Valery a Primordial in Arrive at Easterwine. Only The Lord in "Through Other Eyes" is max, max, max:

“It is almost like looking through the eyes of the Lord, who numbers all the feathers of the sparrow and every mite that nestles there.”

At the end of the story, we find out that Charles is busy building a mediator in the form of the Correlator, which is the ironic ending because that is, in fact the reality that exists, something we see in the subliminal signal line early in the story: "A subliminal coupling, or the possibility of it, was already assumed by the inventor." Because truth must be mediated (assuming Lafferty takes the view of something like 1 Timothy 2:5), the Correlator trades absolute peeping-tom level epistemic disclosure for what already exists:

“The Correlator is designed to minimize and condition the initial view of the world seen through other eyes, to soften the shock of understanding others. Misunderstandings can be agreeable. But there is something shattering about sudden perfect understanding.”

The upshot is that perceptual error is real but graded.

I’ll wrap up with one way of showing it: