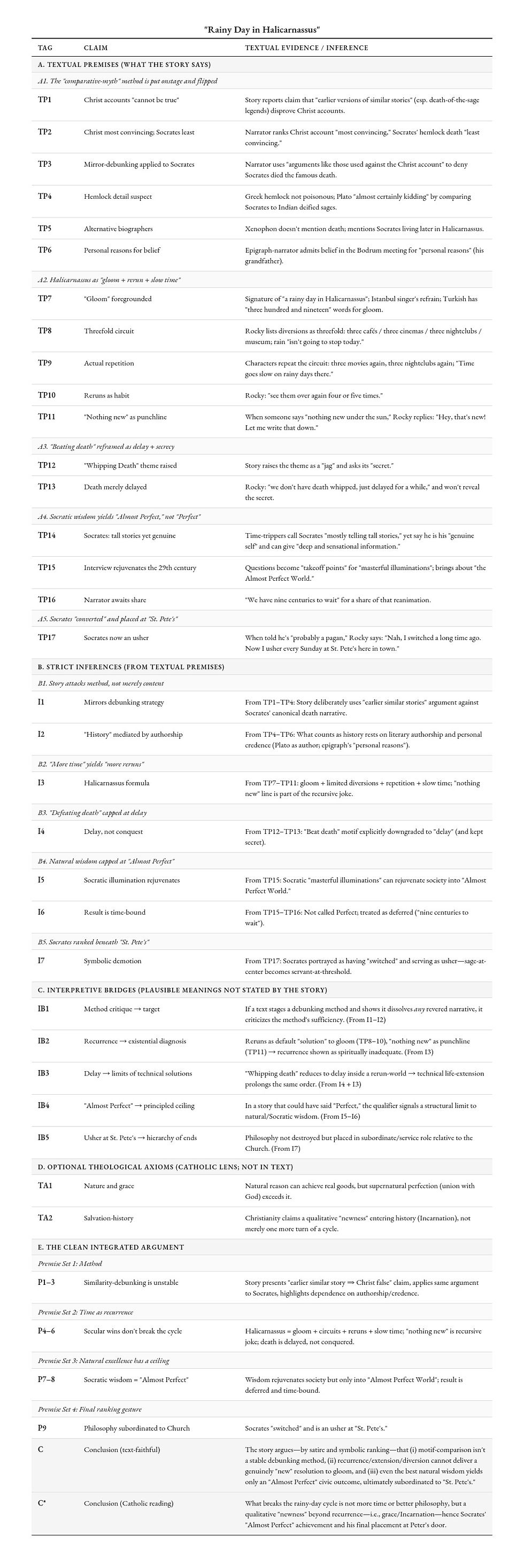

"Rainy Day in Halicarnassus" (1978/1988)

- Jon Nelson

- Dec 27, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Dec 28, 2025

Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way asthe others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened: and one must becontent to accept it in the same way, remembering that it is God’s myth where the othersare men’s myths: i.e. the Pagan stories are God expressing Himself through the minds ofpoets, using such images as He found there, while Christianity is God expressing Himselfthrough what we call "real things." — C. S. Lewis

Here, for as much as hearing could discover, there was no outcry louder than the sighs that caused the everlasting air to tremble. The sighs arose from sorrow without torments, out of the crowds—the many multitudes— of infants and of women and of men. The kindly master said: ‘Do you not ask who are these spirits whom you see before you? I’d have you know, before you go ahead, they did not sin; and yet, though they have merits, that’s not enough, because they lacked baptism, the portal of the faith that you embrace. And if they lived before Christianity, they did not worship God in fitting ways; and of such spirits I myself am one. For these defects, and for no other evil, we now are lost and punished just with this: we have no hope and yet we live in longing.’ — Dante Alighieri, I.1.4

“I switched a long time ago. Now I usher every Sunday at St. Pete's.”

Lafferty and Sheryl Smith had been corresponding for several years by March 1978, their letters filled with discussion of religion and myth, Lafferty filling the role sage, Smith that of student. Smith’s reading of Lafferty was strongly shaped by archetypal criticism, and in that context the question arose of whether Christ might be understood as a fertility deity. Lafferty rejected this outright. “Whether on Frazer’s Lake of Nemi, or in Anatole or Galilee,” he wrote, “the Christus is always a scape-goat figure. This King in every case is born for only one reason, to die an expiatory death. The notion that a story can’t be true because something like it was told previously reminds me of my own short story, ‘Rainy Day in Halicarnassus.’ This is one of the stories that haven’t been written yet, and probably not ever; even the title is here written down for the first time."

Six months later, Lafferty finished the story, which would not see print until Dan Knight saved it for The Back Door of History (1988) collection. Lafferty's letter to Smith sketches out the premise without mentioning the two characters who visit Halicarnassus in the story, characters we know from “In Our Block.” In the Lafferty-Smith correspondence, Lafferty mentions the sages that appear in the final story. He tells Smith that a rainy day in Halicarnassus could be exceptionally tedious if one were stuck there “with the movies closed by a projectionist’s strike.” It looks as if that throwaway line about Smith being stuck there with the sages became the story's plot: swap out her being stuck with the “In Our Block” characters. In his story, movies and repetition play a large role; there is no projectionist strike. In any event, it is fun to find Smith in the story in ghostly fashion because of the role she played; and it is fun to see Lafferty conceiving a story on the fly, then patching it up.

Write-ups and commentary on “Rainy Day in Halicarnassus” are quick to note its high concept: Socrates never died. They also tend to emphasize the other story feature no reader forgets—the pervasive boredom of the rainy days on Halicarnassus, and the small rituals people devise to kill time. But the story does not seem to me to be well understood. In this respect, Lafferty’s letter to Smith is useful because it show that Lafferty conceived of the story as a philosophical argument about myth, archetype, repetition, and Christus, as well as the way narrative confers precedence and power.

As with many of Lafferty’s stories, this one is a thought experiment. The repetition in the story is not just atmosphere; it is the circular loop of natural wisdom without revelation, related to the pagan conception of time as a circle. The story makes it clear that the only exit from that circle is through the Church's door. So what, then, actually happens in the story?

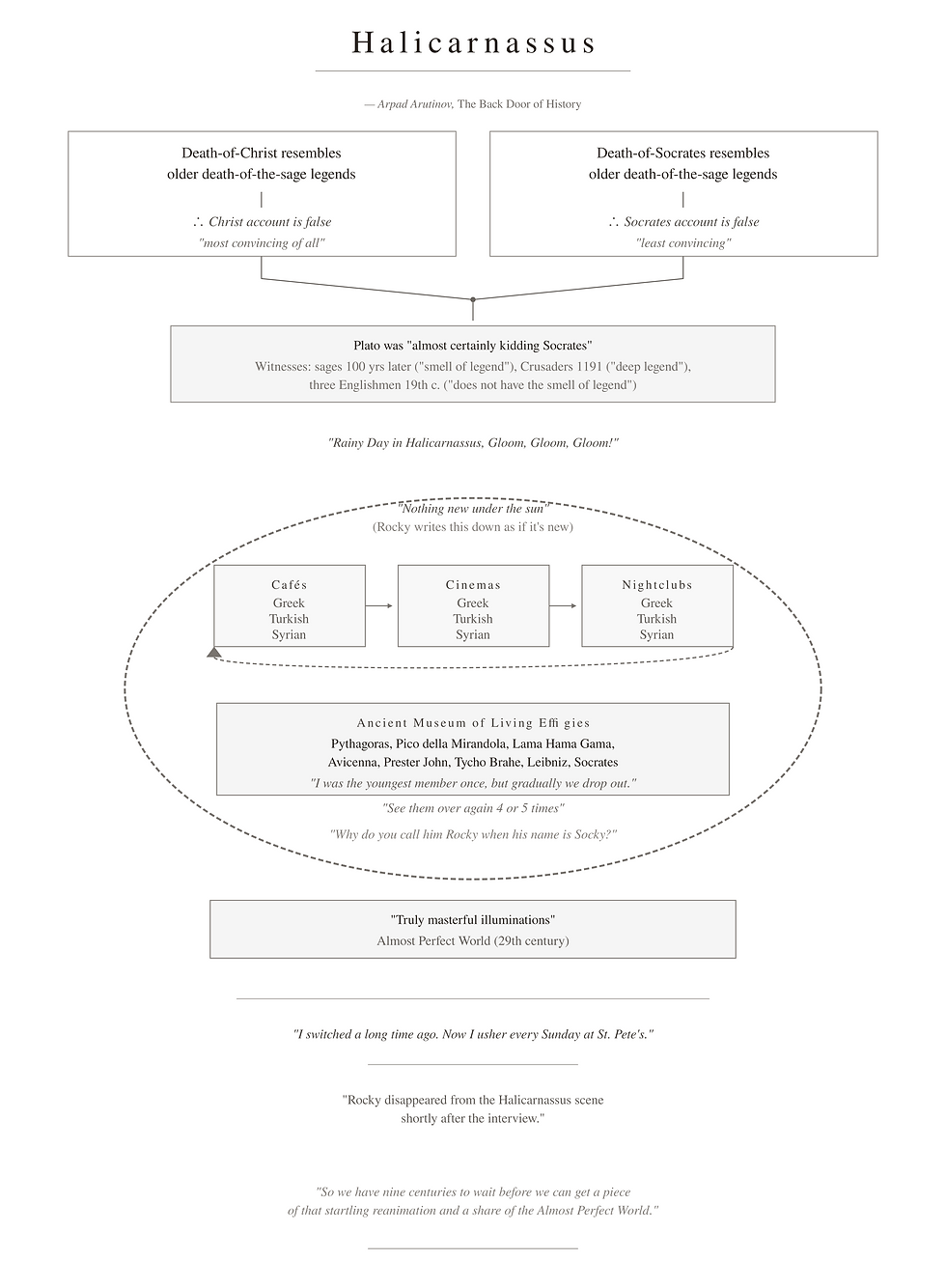

We begin with a paratext by Arpad Arutinov stating that the philosopher Socrates did not die of hemlock poisoning in 399 BC, but continued to live in Halicarnassus, now known as Bodrum, Turkey. This paratext carries far more of the meaning of the story than his paratexts usually do, and they are rarely merely decorative. Then our story kicks off, with two American travelers, Art Slick and Jim Boomer, docking their small boat in Bodrum to escape a storm. The Tulsans find themselves up against a very gloomy rainy day. They are joined by a broken-nosed, stocky Greek local named "Socky"—whom the Americans nickname "Rocky"—who is the ancient philosopher himself, having survived for centuries.

To pass the time in the rain, the trio follows a repetitive circuit. They visit the town's Greek, Turkish, and Syrian cafés, cinemas, and nightclubs. During their excursion, Rocky drops wild claims about history. The two men find out that he learns new languages every few decades and that modern entertainment, such as Western movies and radio acts, originated in ancient times. Even advanced technologies, including aviation, existed in antiquity but were forgotten or dismissed as myths.

The group then arrives at the "Ancient Museum of Living Effigies," where Rocky is the star attraction alongside other historical figures, such as Pythagoras and Avicenna. The routine is interrupted by a "time-inversion shock wave," the intrusive arrival of visitors from the future. A group of "time-trippers" appears, complaining that they have been trying to pin Socrates down for a serious interview every ten years but have been consistently evaded or given ridiculous answers.

The time-travelers plead with Rocky to answer their questions, claiming the information would be a historical coup. Rocky is reluctant, preferring to join Art, Jim, and a local girl for a "Goose-Down-Eve" festival on the island of Cos. But because the rain is relentless and the local movie theaters have not changed their films, Rocky says he has nothing better to do and agrees to the interview to kill time before his boat trip.

The impromptu interview is a success, with Socrates providing profound answers to the visitors' questions. It is revealed that these time-trippers originate in the twenty-ninth century, a stagnant era rejuvenated by Socrates' wisdom, leading to an "Almost Perfect World." Rocky disappears from the public scene shortly after, leaving the narrator to note that the present day must wait nine centuries to share in the result.

This story is so much about flavor and atmosphere that it isn’t really surprising that readings stop there, happy to spend some pleasant time with Socrates in the rain. Going back to Lafferty’s argument with Smith about the nature of myth, though, we can work out some of what is going on here. Simply put, Lafferty has given us what he gave Smith: a reductio ad absurdum of historical skepticism. I doubt Lafferty enjoyed Kierkegaard, but he is on Kierkegaardian ground here. By opening the story with Arutinov’s paratext asserting that Socrates never died—and using the kind of "comparative myth" arguments to debunk the Gospels (already hoary by 1978)—Lafferty sets up a methodological trap. He highlights the absurdity of selective skepticism when Arutinov dismisses ancient records because they have "the smell of legend," yet accepts 19th-century anecdotes based on personal whim: "To me, this does not have the smell of legend. For personal reasons (one of the three Englishmen was my own grandfather), I believe it is true."

If one dismisses every historical event that resembles a prior, say, the death-of-the-sage motif, history dissolves into total legend. Here, I think one also ought to ask, why Halicarnassus? The answer to that is probably history itself, and how history relates to myth, because Halicarnassus is associated with someone very important: Herodotus, the father of history, who was born there. The "Rainy Day" is a metaphor for a vacuum: a closed loop of time characterized by "gloom," where human diversions (the cafés and cinemas) are repetitive "reruns," and where there is literally "nothing new under the sun." Lafferty drives this home with a joke; when Boomer uses that phrase, Rocky exclaims: "Hey, that's new! Let me write that down. 'Nothing new under the sun.' That's good. Into the old notebook it goes." It is a space where there are few real events, like Christ breaking into human history, where everything is thinned by antecedent, though one important event eventually occurs in the story when Socrates restores natural wisdom to the future. They seem to be pretty doing badly out there in the 29th century.

On that last point of natural wisdom, the story is one of the rare ones in which Lafferty is both critical and appreciative. The story praises natural wisdom, but, in Thomistic fashion, delimits what it can offer. As St. Thomas wrote, with natural reason alone, the truth about God “would only be known by a few, and that after a long time, and with the admixture of many errors.” So how to be satirical and still be intellectually generous? This formal problem of generosity in satire and storytelling was on Lafferty’s mind when he wrote to Smith. He put it this way:

Ah, maybe it’s just as well that [“Rainy Day in Halicarnassus”] wasn’t written. Socrates is one of the guys who may not be tampered with.

Lafferty resolves the “tampered with” problem by tampering hard: he makes Socrates a Catholic convert. Within the closed loop of the rainy day, the story marks the hard ceiling of natural wisdom. Socrates is given the role similar to the Dante assigns him in the history of human reason: that of the virtuous pagan. Then he extended grace the way Dante extended it to Cato by installing Cato in Purgatory, the sage having been taken there by Christ during the harrowing. Socrates was not so lucky. In any case, natural wisdom is shown to be capable of rejuvenating a stale civilization in Lafferty’s story. As the narrator observes, the future had “gone stale,” and Socrates’ wisdom “produced one of the most startling reanimations ever,” yet the result is defined as the “Almost Perfect World.”

Natural philosophy can produce technical marvels—perhaps even tricks like “whipping death for a while,” which the story makes clear is delay rather than conquest—and it can generate social improvement, but it cannot cross the gap from “Almost” to “Perfect.” That gap is infinite. This view of natural excellence (arete) vs perfection is exactly what one would expect, given Lafferty’s commitments: it is distinct from, and inferior to, supernatural perfection; bound by time; and insufficient to cure existential gloom. As I alluded to above and have written about elsewhere (“Phoenic”), this is time’s circle, not time’s arrow. The arrow cuts the timeline with singular events, not cyclical repetitions.

The thought-experiment resolution is Catholic in that it does what Church has done since the Church Fathers: subordinate philosophy to theology, making theology the mother of the sciences, philosophy her handmaiden. This decisive turn comes casually: “‘Going back that far, you’re probably a pagan, Rocky,’ Jim Boomer said. ‘Nah, I switched a long time ago. Now I usher every Sunday at St. Pete’s here in town.’”

Why Rocky? Well, because the historical Socrates was a very tough man, a veteran of the Persian War, a stone mason. Rocky the film had come out two years before the story takes place and is set in Philadelphia; hence Lafferty’s wry little joke about a sunny day in Philadelphia:

“The Dictionary of Idiosyncrasies gives it that the equivalent of a ‘rainy day in Halicarnassus’ is a ‘Sunday in Philadelphia,’” this broken-nosed and grinny Greek seaman said. Well, maybe he was a broken-nosed Greek boxer and not a seaman.

I should probably add that Rocky is also Rocky because the great boxers called Rocky in boxing history, men such as Marciano and Graziano.

Why else is Socky called Rocky? Because Christ founded his Church upon Simon Peter, whose name, of course, means rock: “And I say also unto thee, That thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.”

Analytically, this is a fable about reordering the hierarchy of natural ends, which recapitulates the death-of-the-sage motif in the Lafferty-Smith letter: the sage is not destroyed but demoted, reassigned to a servant role at the threshold of the Church. Lafferty’s thought experiment concludes that the only escape from the “Rainy Day” cycle of recurrence is the qualitative newness of grace, which is always both anevent and a state, symbolized by St. Peter. It is a story he has written before but with surface features so different one might not notice. The almost-perfect wisdom of the philosopher is validated only insofar as it leads the soul toward a perfect reality beyond its own capacity. Beyond the cardinal virtues are the theological ones. Socky becomes Rocky, a baptismal name, a Catholic usher.