"In the Garden" (1961)

- Jon Nelson

- Jan 18

- 6 min read

What was it, then, that I, miserable one, so doted on in you, you theft of mine, you deed of darkness, in that sixteenth year of my age? Beautiful you were not, since you were theft. But are you anything, that so I may argue the case with you? Those pears that we stole were fair to the sight, because they were Your creation, You fairest of all, Creator of all, You good God — God, the highest good, and my true good. Those pears truly were pleasant to the sight; but it was not for them that my miserable soul lusted, for I had abundance of better, but those I plucked simply that I might steal. For, having plucked them, I threw them away, my sole gratification in them being my own sin, which I was pleased to enjoy. For if any of these pears entered my mouth, the sweetener of it was my sin in eating it. And now, O Lord my God, I ask what it was in that theft of mine that caused me such delight; and behold it has no beauty in it — not such, I mean, as exists in justice and wisdom; nor such as is in the mind, memory, senses, and animal life of man; nor yet such as is the glory and beauty of the stars in their courses; or the earth, or the sea, teeming with incipient life, to replace, as it is born, that which decays; nor, indeed, that false and shadowy beauty which pertains to deceptive vices. — St. Augustine, Confessions, Book II

“This is still a perfect come-on here. There is something in human nature that cannot resist the idea of a Perfect Paradise. Folks will whoop and holler to their neighbors to come in droves to spoil it and mar it. It isn’t greed or the desire for new land so much, though that is strong too. Mainly it is the feverish passion to befoul and poison what is unspoiled. Fortunately I am sagacious enough to take advantage of this trait. And when you start to farm a new world on a shoestring you have to acquire your equipment as you can.”

“In the Garden” is a simple story, but it sets out a principle that is always present in Lafferty—and that sometimes gets him into trouble: “It is only the unbelieving who believe so easily in obvious frauds.”

We meet the crew of the spaceship Little Probe. It consists of Captain Stark, engineer Steiner, executive officer Gregory Gilbert, tycoon and majority owner Caspar Craig, and the Jesuit priest Father Briton. While exploring deep space, the Little Probe identifies a moon showing traces of life and superior thought. Upon landing, something truly odd happens. They encounter a man and a woman named Ha-Adamah and Hawwah. The two live in a lush, meadow-like environment, bathed in a mysterious light. They claim to be the only humans in existence. They say they possess preternatural intellects, do not experience death or aging, and live in a state of original innocence. Who could they be?

During their stay, Lafferty gives us some light comedy with biblical gags. The man warns the travelers to avoid a specific pomegranate tree while encouraging them to eat from the other trees in the garden. Most of the crew members, including the tycoon Caspar Craig, are duped by it. They believe they have found the biblical Garden of Eden. Craig begins drafting advertisements to sell the land to settlers as "Eden Acres Unlimited." Only Father Briton is skeptical. He sees that the inhabitants' claims are theologically unsound and that the man’s refusal to play a game of checkers, claiming he does not wish to "humble" the priest, shows his "preternatural intellect" is a fraud.

After the Little Probe departs to round up settlers, Lafferty reveals the fraud. A criminal named Snake-Oil Sam works out of a nearby cave filled with stolen machinery and a pile of bone-meal. He uses actors, scripts, and itchy, shining paint to impersonate Adam and Eve. The garden is a "come-on" to lure well-equipped settlers to the moon so that Sam’s gang can murder them and seize their machinery and spacecraft. The story ends with the Little Probe crew divided on the truth of the site; aside from Father Briton, they are unaware that they are unwittingly acting as Sam’s agents. It’s a trap that has already claimed thirty-six ships.

An absurdly high-toned detour, but one that helps clarify what “In the Garden” is doing. In Critique of Pure Reason, Immanuel Kant put the transcendental argument on the map. In its original context, Kant wanted to show that the pure concepts of the understanding must exist. Without them, experience would be flying blind. Abstracted from that context, a transcendental argument identifies what must already be in place for something else to be possible. It argues that a certain concept or condition (X) must be a necessary precondition for some undeniable feature of human experience or thought (Y). By showing that Y requires X, the argument tries to establish X’s necessity.

Something like this is at work in Lafferty’s “In the Garden.” The con works on everyone except the Jesuit, because everyone in the story is fallen, and only Father Briton has the religious formation to see what is happening.

“People aren’t becoming any smarter—but they are becoming better researched, and they insist on authenticity.”

No one in the story is remotely tempted by the forbidden fruit. This is not Eden. This is after-Eden. The pomegranate is a prop. What tempts the crew is destroying Paradise. It is cacoethes corrumpendi or St. Augustine and the pears. This would have been bread-and-butter in Lafferty’s own moral formation at his Augustinian prep school, Cascia Hall. The means of corruption is commodification: “Ninety Million Square Miles of Pristine Paradise for sale or lease.” The transcendental argument is that the gnostic con-garden points to the real one, because everyone in the story bears postlapsarian scars. In "In the Garden," the universal recognition of the counterfeit garden as a temptation (Y) presupposes the prior reality of a true Paradise and a Fall from it (X), without which the con would be unintelligible.

This is prenucleation Lafferty, and Snake-Oil Sam is about as thumpingly didactic as it gets: “Mainly it is the feverish passion to befoul and poison what is unspoiled.” Snake-Oil Sam is a fun character, and he pretty much embodies A. W. Tozer’s old line that the devil is a better theologian than we are, but he is still a devil. The compulsion to desecrate the sacred is the Fall, not as an event, but as a condition. Original sin. Sam is the serpent in judgment form. He waits for original sin to reveal itself through its response to innocence and completion.

My favorite image in the story is the bone-meal pile, the story’s real image of Hell. I wouldn’t want to argue that Sam has a connection to Samiel in Gnosticism, but Samiel is, of course, important to that tradition: a demiurgic figure associated with ignorance, material bondage, and forces that oppose divine knowledge (gnosis). He is connected to the archons who trap souls in the material world.

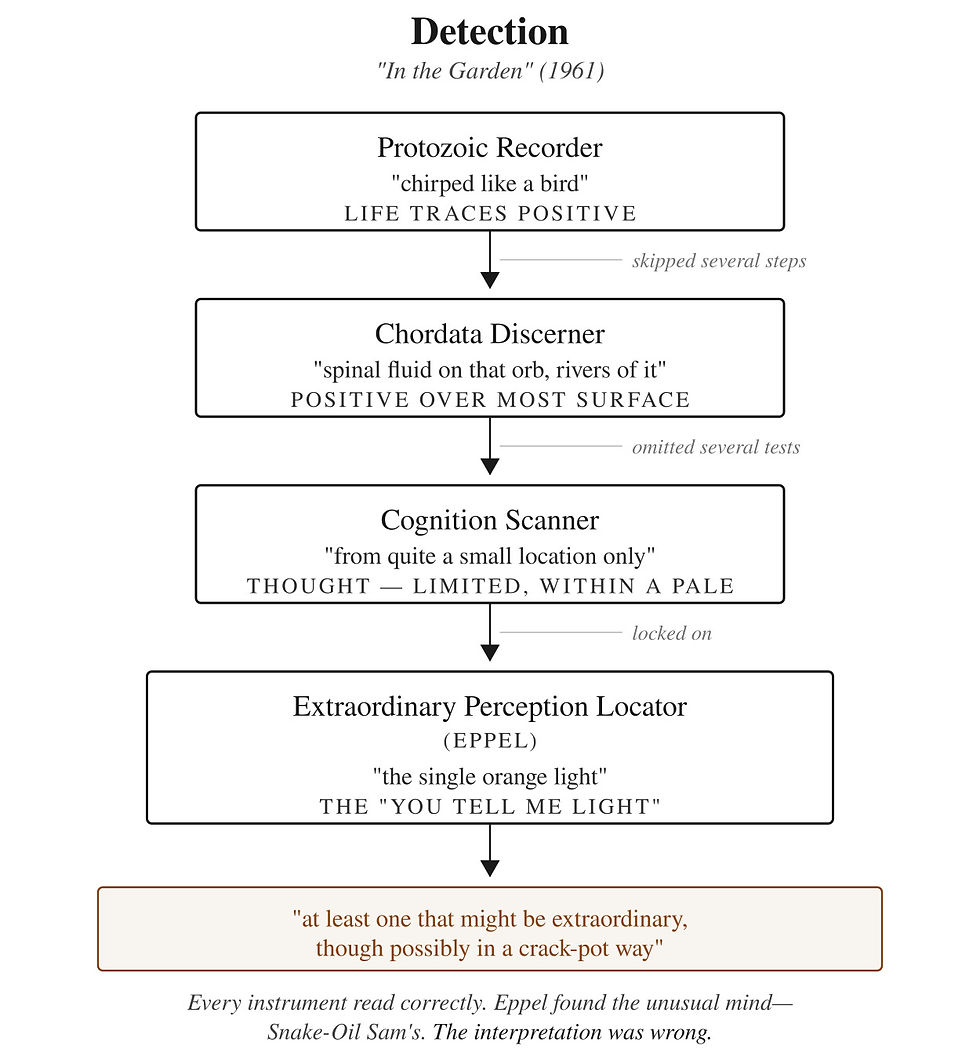

In any case, Briton sees through it. Faith gives him better tools for skepticism. The skeptics trust their senses. All the machines give correct readings in this story, which matters. Lafferty makes the point repeatedly: the machine is correct, the machine is correct, the machine is correct. Then he makes his real point: empiricism without metaphysics is defenseless. Machines have no theological criteria for what prelapsarian existence would be. Briton does. A being before the Fall would not possess knowledge of death or other unfortunate worlds. A preternatural intellect would not fear checkers.

Andrew Ferguson has pointed out that the story’s last line might have been added by If. I would not be surprised. The tacky last line does not read like Lafferty. Ferguson’s other idea—that the line might be meta-satirical, with Lafferty using it to criticize a character’s misogyny or misogyny in the science-fiction field—strikes me as wishful. Ferguson writes, “the story ends on what I read as a jab at the misogyny still rampant in the field; namely, the flunky asserting that the planet for its evident fault was still paradise in the sense that the woman didn’t speak.” Sure.