Conspiracy and "About a Secret Crocodile" (1970)

- Jon Nelson

- Oct 14, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Nov 9, 2025

“There is Cavour. He has hardly begun in the world, but look how well-developed his web is. There is Lord Acton in England. There is Montalambert. There is poor Lamennais who will officially go to Hell. There is Mordecai or Marx who has been spinning a web in Paris and other places. Notice the exceptionally long anchor lines of his web, though the body of his web will always be paltry.” — The Flame Is Green (1971)

“There is a secret society of eleven persons that is behind all Bolshevik and atheist societies of the world. The devil himself is a member of this society, and he works tirelessly to become a principal member. The secret name of this society is Ocean.”— “About a Secret Crocodile”

Today, I want to consider John Clute’s observation that R.A.L.’s work is irradiated by conspiracies. This is so evidently true that it is surprising how rarely Lafferty’s readers have attempted to trace the logic of conspiracy in his fiction. At a certain point in reading him, it became clear to me that two distinct forms of Catholic-inflected conspiracy are typically at work, often in allegorized or displaced form.

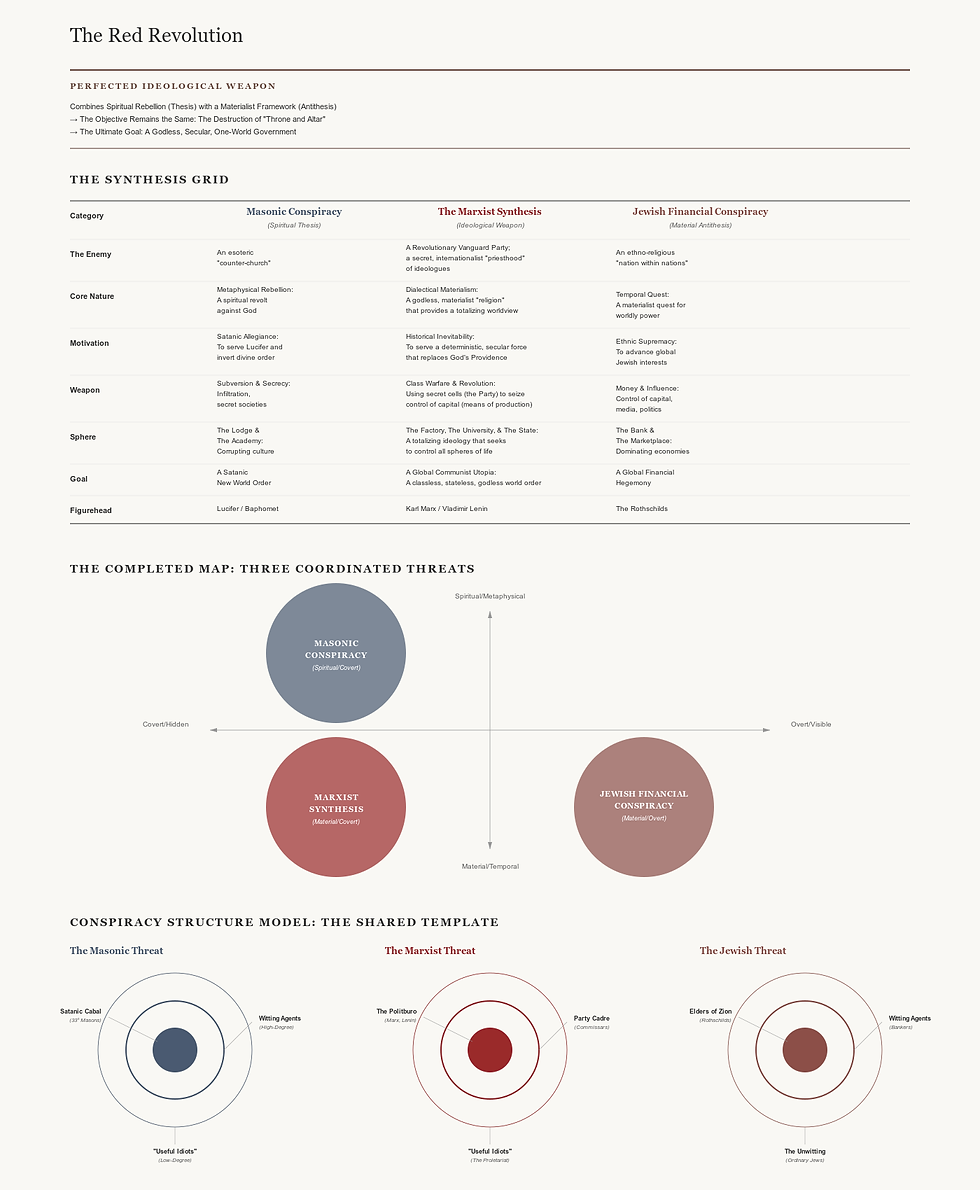

One version leans into 19th-century ideas about Satanic Freemasonry. This is complicated by the fact that some Catholics have viewed Freemasonry as being a crypto-Jewish organization. For instance, in The Jews 1922, Belloc makes this argument. This can be distinguished from Satanic Freemasonry where dark political and spiritual forces are joined in an alliance against the Church. Its roots reach back to the early 18th century, grounded in anxieties over the Masons' secrecy, their perceived indifference to religion, and their supposed threat to Church authority.

In 1738, Pope Clement XII issued In eminenti apostolatus, a bull that excommunicated any Catholic who joined a Masonic lodge. His successors, including Benedict XIV, Pius VII, and Leo XIII, reaffirmed and extended this ban. The theory reached a theatrical peak in the Taxil hoax, the source of some embarrassment, but not enough to alter the Church's social teaching. In 1983, the revised Canon Law no longer named Freemasonry, but the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (the modern continuation of the Inquisition, most recently renamed by Pope Francis as the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith) clarified that the prohibition still stands. Catholics who join Masonic groups commit a grave sin incompatible with Church teaching. That means they go Hell for it unless invincibly ignorant.

A second version of the historically conspiratorial is less cosmic but no less threatening. Here, the danger is political rather than uncomplicatedly Luciferian. This is where one finds the view of someone like Hilaire Belloc, who argued that Jews posed a persistent political threat to Christian nations, in part because they remained, in his eyes, a distinct nation living inside others. This led to a tragic cycle: welcome and prosperity, growing friction, antagonism, and persecution, which repeats itself through geographical relocation. Alongside Belloc, Lafferty saw Islam not simply as another religion but as a heresy. And in his thought, he occasionally presents both Jews and Muslims as conspirators against the Catholic faith, particularly in the context of Spain. A close reading of Sinbad: The Thirteenth Voyage convinces me that Lafferty’s portrayal of Islam includes infernal qualities, linking it more closely to the Freemasonic strand of my two-front theory of Catholic conspiracy.

Importantly, there are also mixed modes. This, I think, is how Lafferty understood the role of Jews and Muslims in Spain and their conspiracy against Christendom. To him, the historical alliance had an infernal tinge because it was so deeply anti-Catholic. The most dangerous historical hybrid, however, for modernity is not anything like this, but new. It is embodied by the first of his great devils, Ifreann Chortovitch (Coscuin) whose sons are central to Argo. It is the atheistic threat of Marxism and the Red Revolution, which Lafferty saw both infernal and Jewish (in novels and short stories, he calls Marx as Mordecai). That conspiracy combines economic materialism with spiritual corruption. We see this idea developing in the unpublished Civil Blood and running throughout the Coscuin Chronicles and Argo.

With this two-front war model and the possibilities of historical partnerships and sublimations in place, we have a little more to work with than simply saying there is an awful lot of conspiracy in Lafferty.

A good place to look at how this works in his short fiction is “About a Secret Crocodile.” It is one of the first Lafferty stories anyone should read, one of his best. It shaves off the content of real history and instead creates a comedy about the machinery of conspiracy, making more apparent the functional traces of the two kinds of conspiracy I’ve outlined above.

The story world is secretly run by a powerful being called the Secret Crocodile. Its main goal is to “control the attitudes and dispositions of the world.” It works through a front company called ABNC and is supported by high-level agents like Mr. James Dandi and John Candor, who have gone through a kind of “catechesis.” The Crocodile is totalizing. It is the central hub where all conspiracies converge. It oversees smaller conspiracies, such as a “cabal of seven men controlling the finances of the world,” as well as opposing movements like “Ocean” (which backs Bolshevism) and “Glomerule” (which backs Fascism). Through this structure, the Secret Crocodile shapes global consciousness, making sure that major world events serve its purpose.

One day, the system goes on high alert. There is a threat from “the Randoms,” a trio of people who are “unknowingly linked” and act “without program or purpose.” The group—Mike Zhestovitch, Mary Smorfia, and Clivendon Surrey—is not a counter-cabal. They are an organic anomaly. Their strength comes from raw, authentic human reactions that the system cannot fully manage: Mike’s “gesture of contempt,” Mary’s “grimace of disgust,” and Clivendon’s “intonation of scorn.” Lafferty presents these as pre-ideological weapons—graced forms of spontaneous spiritual resistance that threaten the Crocodile’s system of manufactured consent.

The trio is exposed after a series of absurd office mishaps, ending when an underpaid employee, Betty McCracken, feeds her awful sandwich to the office computer. The system’s first response is to try to corrupt Clivendon Surrey. Agent Morgan Aye offers him a vast fortune. Surrey rejects it with a snort of contempt, saying, “Then I’d be one of the birds that picks the shreds of flesh from between the teeth of the monster.”

After failing to corrupt the trio, the organization turns to physical violence—what it calls “the Compassion of the Crocodile.” Dandi and Candor authorize a “Purposive Accident,” a carefully planned bombing meant to neutralize the Randoms’ abilities. The attack works exactly as intended. Mike Zhestovitch’s hand is mutilated, Mary Smorfia’s mouth is disfigured, and Clivendon Surrey’s vocal cords are destroyed. By damaging the physical sources of their resistance, the system silences them.

The story then moves to its real ending, where Lafferty steps in as narrator to comment on what is going on. Somewhere out there, beyond the reach of the Crocodile, there is a force that can resist it. It is “the good guys and good gals,” a vague, unmapped potential for decency that exists entirely outside the logic of conspiracy. It has no structure, no control, and no program. But it “stirs a little.”

How does this relate to Lafferty's imagination? The Secret Crocodile is a full synthesis of what I called the “Two-Front War.” It has institutionalized the material drive of the Jewish Financial Conspiracy within its Financial Arm and absorbed the spiritual rebellion of the Masonic Conspiracy, along with the Marxist synthesis, into its Political and Cultural Arms. By managing both the Bolshevik front, called “Ocean,” and the Fascist front, called “Glomerule,” it keeps a firm grip on everything.

. . .

This is an attempt to bring some of these thoughts together. On the Crocodile Org diagram, you’ll notice the labels material and spiritual. This is a really gross simplification. Lafferty maintains that both fronts are always present—for example, the Devil belongs to the materialist front, matching what we find in his ideas about the Red Revolution in Coscuin and elsewhere.