“Boomer Flats” (1971)

- Jon Nelson

- Mar 20, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Oct 28, 2025

Lafferty had a soft spot for Neanderthals and every kind of ape-man. My favorite instance of this appears at the end of Arrive at Easterwine (1971), his most spiritual novel, where Epikt adopts his walking ape extension, holding a tin plate in one hand and a giant knife in the other.

Lafferty’s fascination with prehistoric hominids has made me wonder what he knew about them. Had his library survived, it might have revealed something about his reading on the subject. In its absence, we can trace one influence behind his use of the trope.

Whether in The Men Who Knew Everything stories, The Elliptical Grave, or the story I want to focus on here—“Boomer Flats”—Lafferty’s depiction of prehistoric hominids is shaped by a moment in early twentieth-century intellectual history.

It was an episode that drew considerable press attention and became a defining event in the writing lives of two of Lafferty’s favorite authors, Hilaire Belloc and G. K. Chesterton: their public brawl with H. G. Wells over his Outline of History (1919–1920).

Wells was an atheist and a public intellectual eager to popularize Darwinism, and he leaned heavily on the idea that Neanderthal man posed a threat to belief in the God of ethical monotheism. For him, the prehistoric hominid was not just a scientific curiosity but a real blow to divine creation.

Belloc and Chesterton disagreed. They saw in Wells more than a dispassionate interest in furthering scientific literacy. He was a progressive moralist, and Neanderthals were part of a broader ideological project, consistent with Wells’s other social views on ideas like free love. All aimed to undercut traditional religious and anthropocentric convictions. To them, the Neanderthal in Outline of History wasn’t a neutral piece of data from deep time but a polemicized weapon.

One could hardly look at the illustrations of Neanderthal man in Wells’s Outline and not sense how jarring the contrast would be when set alongside Hamlet’s encomium: "What piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving, how express and admirable in action, how like an angel in apprehension, how like a god! The beauty of the world. The paragon of animals."

Chesterton took up arms against Wells in several places, most notably in The Everlasting Man (1925), and returned to the subject of Neanderthals in essays throughout the years following the debate. But the fiercest counterstrike came from Belloc in Mr. Belloc Still Objects to Mr. Wells’s Outline of History (1926).

[Wells] has got hold of the idea that the discovery of Neanderthal skulls and skeletons destroys Catholic theology. He imagines that we wake up in the middle of the night in an agony of imperilled faith because a long time ago there was a being which was as human as we are apparently in his brain capacity, in his power to make instruments, to light fires, and in his reverent burial of the dead, but who probably, perhaps certainly, bent a little at the knee, carried his head forward, was sloping in the chin. (24)

In a private letter, Lafferty wrote that Belloc and Chesterton were the best writers in England in their day. Whatever one makes of that judgment, there is no doubt they loomed large in his imagination. He was an indefatigable reader of everything the two men wrote. His own style is in part a blend of the two writers. From Belloc, he takes the epistemic stand toward truth one finds in classical prose. From Chesterton, he takes the funhouse mirror approach to how surprising truth can be.

In short, the bent, simian extension that Epikt takes at the end of Arrive at Easterwine had long lived in Lafferty’s imagination. The posture, the physiognomy—none of it is threatening to faith, is its import. Here, modernity is absorbed, not resisted. And so the hominid figure became a recurring motif for him. He turns it on later thinkers like Pierre Teilhard de Chardin who comes in for particularly brutal treatment.

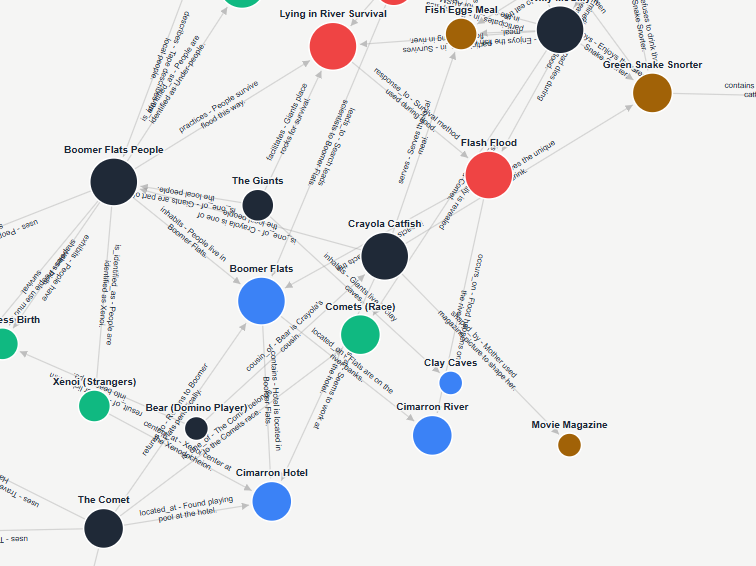

To see how this can play out in Lafferty's work, consider "Boomer Flats," a story whose plot, though risky to paraphrase, involves three eminent scientists—Arpad Arkabaranan, Willy McGilly, and Velikof Vonk—who travel to a ragged riverside settlement called Boomer Flats in search of legendary missing links, known as ABSMs (Abominable Snowmen).

There they find a community living by the mud-banks of the Cimarron River, where people mix with bears, giants, and a figure known only as the Comet. Despite the apparent primitiveness of the locals, two of the scientists—Willy and Velikof—recognize that these folk are not monsters but something deeper: an underlying “scrub” race of humanity, the foundation beneath modern man.

When a catastrophic flood arrives, the Boomer Flats inhabitants survive in a strange ritual: they lie beneath the river with stones on their chests. Willy and Velikof join them. Arpad panics and dies. The two who remain gain a broader, stranger understanding of what it means to be human—one that includes comets, giants, and catfish spirits.

So what is going on here if we read the story in light of the Neanderthal debate?

On one side, we have Wells, whose evolutionary materialism claims that prehistoric hominids are natural facts that disprove biblical accounts of creation and providence. On the other, we have Belloc and Chesterton, who think this misses the point, and that prehistoric hominids, if anything, just point to the complexity of the Divine plan and the broadness of the human family.

Lafferty sets this up as the conceit of three scientists looking for the missing link—abominable snowmen—in rural Oklahoma, which is funny in itself. What the story becomes is theological anthropology.

Arpad Arkabaranan ends up being the Wellsian figure. He yearns for the empirical, sensational missing link. His name perhaps even points to his rigid mindset. Our old friend Willy McGilly is our Chesterbelloc stand-in. He’s comfortable with paradox. Local lore doesn’t bother him at all because he embodies Chestertonian (un)common sense. And then we have Dr. Velikof Vonk, who we learn is a neo-Neanderthal, one of the story’s most playful ideas: the missing link always among us, civilized, witty, and Catholic-friendly.

The dynamic of the three “Magi,” one of them unworthy, culminates in Arpad’s refusal to accept the mud-based baptism from the flood. It is as if Lafferty is saying something like, look, it’s not the existence of “missing links” that threatens faith, but the inability to see how they are integrated into the sacramental continuum of creation—what I have called Lafferty’s sacramental poesis.

As elsewhere in Lafferty’s work, mud and clay carry deep symbolic weight. He renders mud both comic and cosmic. The image of mothers licking their children into shape recalls God forming Adam—whose name means red clay—from the dust and breathing life into him. Here, the raw stuff of the earth is sacramentalized: the grimy Cimarron River, rightly seen, is not filth but grace. As Willy McGilly knows, good fish egg stew has “a tang of river sewage”—no part of matter lies outside God’s redemptive design.

The theological anthropology comes to the fore with the question of the under-people in the story. They are shabby, mud-homely, shapeless. They inhabit the margins of time and places. But they are integral to who we are now as part of the human family—“the scrubs that bottom the breed,” as Lafferty puts it, the “foundation.”

Over the course of the story, we find out that Vonk is one of these people, and we also learn that Willy McGilly is one of the Comet people in the story, someone who understands and exhibits the starry, universal dimension of Catholicism.

“Boomer Flats” is a wonderful story. It’s also a pointed critique of H. G. Wells, the enemy of Lafferty’s heroes, a recurring fight that can reappear when Lafferty confronts his own adversaries, whom he sees as furthering the Wells agenda in his own time. In the story, the missing link turns out to be ordinary and extraordinary, which is very Chestertonian. The ABSMs are people in an unexpected, expected, sacramental dimension.

The Chesterbellaffian rejoinder to neo-Wellianism comes through loudest in Willy McGilly’s radical acceptance that none of the weirdness poses a threat: all rational souls are shaped within a single, incarnational continuum.

Finally, it might be worth noting how Lafferty transforms the Wells–Belloc debate into an invitation for the reader to participate. This culminates in a rare move in a Lafferty story. It is about as evangelical as he ever gets, and perhaps it is a sign of how personal this story was. He gives us his version of Romance’s great unifying device, de te fabula narratur: this story is about you, dear reader. He writes:

One more is needed so that this set of Magi may be formed again. The other two aspects being already covered, the third member could well be a regularized person. It could be an older person of ability, an eminent. It would be a younger person of ability, a pre-eminent. This person may be you. Put your hand to it if you have the surety about you, if you are not afraid of green snakes in the cup (they'll fang the face off you if you're afraid of them), or of clay-mud, or of comet dust, or of the rollicking world between.

Current notes: