"Puddle on the Floor" (1976)

- Jon Nelson

- Jul 3, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 25

Martin Crookall has done fun blogging on Lafferty. He is one of the few Lafferty readers who writes about the novels, which makes him a hero in my book. He likes to say that Lafferty has about two hundred fans. If by “fan,” Crookall means someone who enjoys the short stories, or someone who liked Past Master and keeps a fond place for Lafferty in memory, then 200 would be an absurdly low number.

But Lafferty fans are an odd lot. Few read his works the way typical fans of a writer do, tenaciously. As I have said before, you won’t find the Sherlockian impulse in most of them. There is little talk about the novels, fitting them together, and trying to make something coherent of it all, even if that something is an unspoken sense of what the millions of words add up to. If that is the kind of fan Crookall has in mind, then he’s probably right. Lafferty does not attract many fans like that. I know about ten.

It's not worth going into the reasons. If you read this blog, you have your own sense of what went wrong and some hope for what could go right. Today I want to focus on a problem that takes a few moments to work out. Lafferty built it into the phenomenology of reading him and baked it into his compositional strategies. It is his unrelenting tendency to overwrite. Not in the pejorative stylistic sense. In the literal sense. Lafferty writes over other texts. He writes on top of them. He writes on top of himself. You can see them in, out, and through his texts.

This is not standard-issue intertextuality. It’s interactively associative. In reading Lafferty, you re-enact his associative patterns in a way that few writers allow. It's intimate. Most writers block our access to the process. Lafferty lets us see it. He knows most of us won't get it. This is closer to the demands of poetry than prose. In some cases, traditional interpretation can sniff out the trail. It can say, “This came from there, and here’s what it might mean.” But often, it can’t. A huge part of the Lafferty pleasure comes from moving, in real-time, through the associations of a rich and strangely stocked mind. Such is the experience of reading the lafferties.

As a reader of his, I always strive to get closer to the associations. I like to think about the materials Lafferty puts into play, not because they usually offer a hermeneutic key, but because they reveal how the story is thinking. The present tense is important here. His stories are thought in motion. This is where Lafferty loses potentially hardcore readers. The less hardcore won’t care enough about the Ur materials. The more hardcore might go looking for mortises and tenons, only to be disappointed by how loosely they sometimes fit.

Over the past year, I’ve started thinking about this aspect of Lafferty as being like Charlie Chaplin fighting the Murphy bed.

I want to call this palimphany: a sequential aesthetic effect through the layers of overwritten text, a flash through half-erased layers of association. Kinetic association. Sometimes it becomes epiphanic. Sometimes it doesn’t. But even when it doesn’t, Lafferty's aesthetic magic depends on it. It’s how he gets you where he goes without explaining what he does. And because he so often won’t even begin to explain it, it’s important to pick up on it. It's the wave-induced orbital motion beneath the smooth surface of the wave.

To see what I mean, let’s look at a Lafferty story I love: “Puddle on the Floor.”

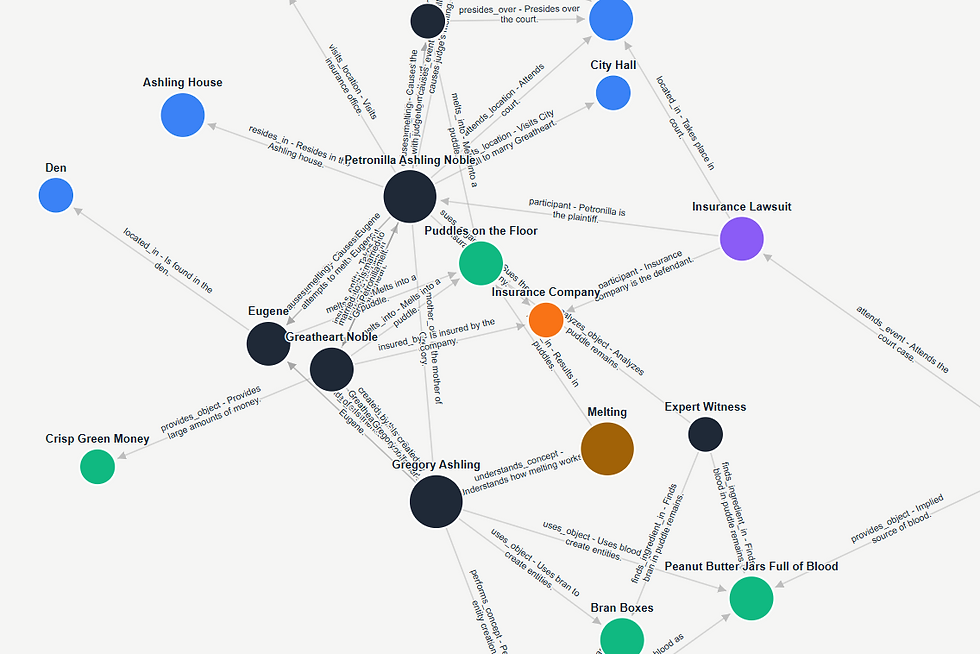

It’s a wild one. Briefly: Petronilla Ashling is a widow. She has a six-year-old son named Gregory. He’s odd, evasive, and strangely self-possessed. He spends long hours with an unseen companion, but Petronilla can never catch them together. Every time she tries to confront them, she fails. The companion vanishes, and in his place, a strange puddle appears on the floor.

Meanwhile, neighborhood pets begin to disappear. Later, it’s reported that cats are turning up with anemia. Petronilla starts to suspect that Gregory is involved in something strange. She’s right. He has found a way to make living figures out of bran and blood. At her request, he creates one—a man named Greatheart Noble, a kind of invented father. She takes out a life insurance policy on him. When Greatheart melts into a puddle, she tries to collect. Her plan falls apart in a courtroom, where the judge turns out to be one of the bran-and-blood creations.

Start pressing on the walls of this story, and you’ll find Murphy beds everywhere. One of them leads to Petronilla de Meath, the first woman executed for witchcraft in Ireland. She was from Kilkenny and connected to Alice Kyteler, an older woman accused of killing her husbands for money. Kyteler escaped. Petronilla, tortured and burned, did not. Kilkenny is also the home of the Kilkenny cats, who gave their name to the idiom about a fight with no survivors.

Petronilla. Witches. Cats. We’re primed. The little girl in the story is named Strega O’Conner. A strega is an Italian witch. The “husband” that Gregory creates—Greatheart Noble—says he is from Transylvania and that he is currently asleep in his castle and ensorcelled in the world of Lafferty's story. Noble wears scarlet, gold, and purple. Lafferty writes,

Greatheart was very tall, and on his head he wore some kind of shako. He had hussar mustaches, and a chest like a pouter pigeon. Draped in a scarlet and purple cape, clad in a scarlet and gold tunic, he was belted and booted in polished black leather.

Here is where it gets really fun. These are the colors of Ferdinand I,

. . . who lived in the castle most often linked to Dracula. The name of that castle? Bran Castle.

“Fine. I like that name,” Petronilla Ashling said.“I'll go get the marriage license now. And I'll go get something else.” She went out to go about her errands, and she waved across the street in a new friendly fashion to Strega O'Conner, who was jumping rope and singing a rhyme: “This is the wife who lost her man, And made her another from blood and bran.”

Now we have Bran Castle, Count Dracula, Ferdinand I, witches, cats, blood-drinking strigoi, and jars of peanut butter filled with blood. Lafferty’s one-of-a-kind associative engine is running hot.

We learn that Gregory’s mysterious playmate, Eugene, slips into trances in his home world when they’re together. The story doesn’t reveal who he is, but we can infer it. And the neighbors? Hermione, like Hermes, the messenger, carries rumor. Mrs. Pettegolezzo? Her name means “gossip” in Italian. It also derives from fart. The same kind of social fart, of course, that gets witches burned.

What are these? They aren’t symbols or clues. They aren’t buried meanings. They’re on the surface of the text. All we have to do is pull the Murphy beds down.

They are not decorative touches. They are structural elements, but they form an associative structure, which is not how we usually think about structure, or at least not how I do. Their narratological function is associative and connective. To explain them is not to decode but to follow the line of thought that put them there.

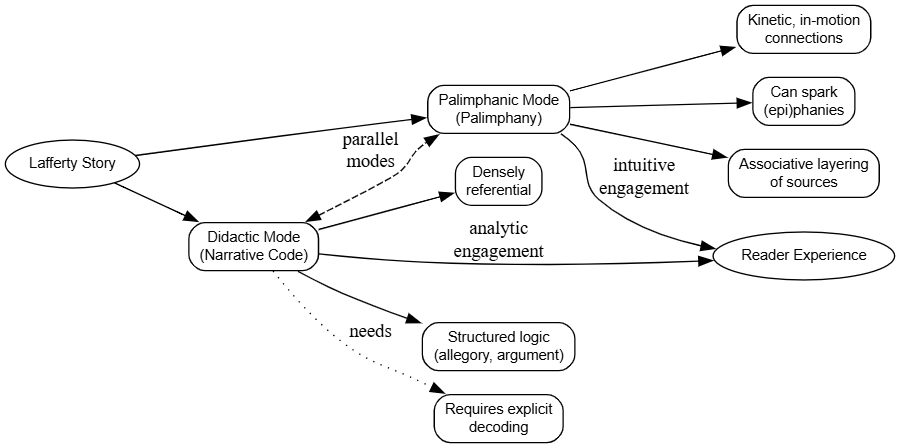

To be clear, Lafferty does require decoding because he is so learned, and some stories are built to be solved: they are densely referential and structured like arguments, allegories, and anagogies. This is the didactic Lafferty. But there is another parallel mode, the palimphanic, that does not melt into code; again, it moves by association. Here, Petronilla Ashling is somehow Petronilla de Meath, a case of metonymy that is more than metonymy, less than metaphor. Lafferty gives us the name. There’s nothing to solve. The meaning is the concatenation that results in a collision: Petronilla de Meath, Castle Bran, Ferdinand I, le strege. Ashling means dream, and Greatheart Noble, if he is Ferdinand I, knows he is trapped dream ("I believe that my real body is still sleeping in my castle in Transylvania"). Gregory is at one point "pretending to be still half asleep, but he was only pretending." Both narrative code and palimphany operate within the same story. Figuring out where one ends and the other begins is what Lafferty fandom could do.

What makes “Puddle on the Floor” so interesting and creepy to me is the way domestic comedy, childish imagination, and adult logic get pulled together by the force of Lafferty’s associations. It’s similar to what happens when certain materials touch and separate. Think of the plastic rulers and wool cloth handed out by an elementary school teacher. Electrons shift. A charge builds. That charge creates a field that pulls on nearby objects. If the conditions are right, it can hold small things in place without touching them. Suspension. It’s a delicate business, this.

That uncanny suspension is like the bran-and-blood suspended people in the story. Tug on them, and their arms come loose. Their heads roll off. Too much pressure, and they lose their shape completely. They melt into puddles. How did these figurations come together in the first place? In the creative act, there can be no answer, but we can look over Lafferty’s shoulder because he has invited us to look.

Maybe Lafferty was reading about Transylvania and Castle Bran in his Encyclopedia Britannica, the set in the background of a photo of him in his comfortable living room chair in Tulsa. He stumbles on a detail; it sticks. He thinks: witches. Petronilla de Meath. Then he invents the name Strega O’Conner and laughs. Or maybe it went the other way—maybe he started with Irish witchcraft and layered in the kitschy Transylvanian stuff later. Maybe it was none of that. But the reader can see the suspension, the elements that are present.

Has Petronilla been brought back to say something? What is the story saying? If I were trying to give a full reading of the story, I would probably press on this. But for now, in thinking about Lafferty’s palimphanies and associative-structure elements that are everywhere in his writing, I want to say this: going deeper into his work means finding them, noting them, and recognizing that these pieces are not quite a secret code, nor are they separable from the effects he creates. We do not have a good way for talking about them in the weird parallel mode he invented.

For me, the most challenging pleasure in reading Lafferty comes in this middle space. We watch the brilliant mind work. The associations shift and connect. The story’s effects rise out of that movement. We can sense the orbital energy move. The shape of the story forms from waves. We can feel the story pulling together through strange rhythms and patterns, but when we try to analyze it, the details get harder to hold onto. This is one of the ways Lafferty feels ghostly. And it is why I do not think you can understand, as opposed to experience, how he lands final lines like the conclusion of “Puddle on the Floor,” even if you sense that behind it a lot is going on:

Petronilla was attempting to drag the judge back to his place on the bench, and that shrinking judge was resisting. Then—oh horror!—Petronilla pulled one arm clear off the judge— And Strega was rope-jumping and rhyming— And the head fell off and— Chancery courts were very informal in those days. This condition has since been corrected.

Good God. We pulled too hard. There is a puddle on the floor.