"Oh Whatta You Do When the Well Runs Dry?" (1974/1984) & "Fall of Pebble-Stones" (1977)

- Jon Nelson

- Sep 8, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 9, 2025

"Fall, at Pel-et-Der (L'Aube), France, June 6, 1890, of limestone pebbles. Identified with limestone at Château-Landon—or up and down in a whirlwind. But they fell with hail—which, in June, could not very well be identified with ice from Château-Landon. Coincidence, perhaps." — La Nature, 1890-2-127, as quoted by Charles Fort in The Book of the Damned (1919)

Forteans today.

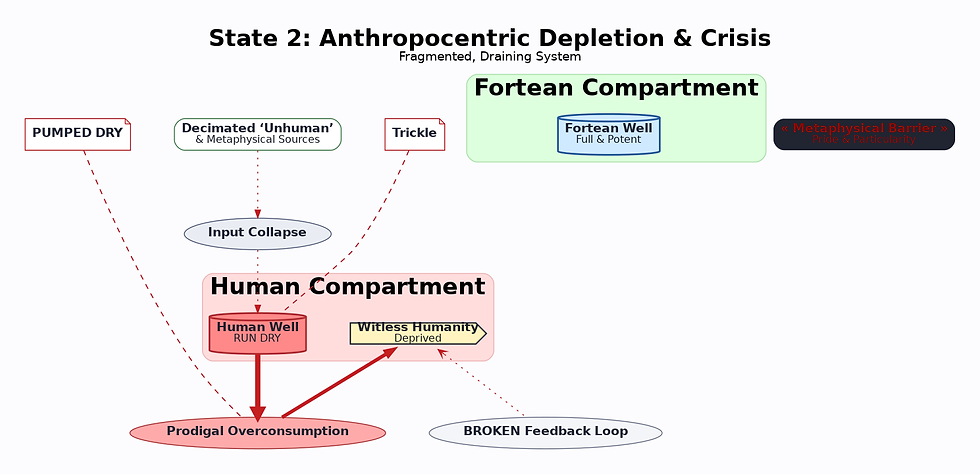

In “Oh Whatta You Do When the Well Runs Dry?”, the world is thrown into chaos when the well of all human creativity, wit, and inspiration suddenly runs dry on November 7, 1999. Society begins to collapse into a witless stupor, and a group of the world's most brilliant leaders convenes. And is stumped. They are powerless, cut off from the source of the kind of ingenuity needed to solve the crisis, but the solution eventually comes from a group of Forteans, who explain that humanity had merely depleted its own small, isolated compartment of a much larger cosmic well. By breaking down the barriers and merging humanity's dry basin with another potent, wild, raunchy source, they restore creativity to the world. There is a cost: humanity is transformed, now permanently drawing from a shared, chaotic wellspring that, a final note in the story reveals, dictates the nature of our own consciousness.

This is an interesting story—one that belongs to a group we might call Lafferty’s Fortean tales. Others in this set include "Sky," "Fall of Pebble-Stones," "When All the Lands Pour Out," "Bequest of Wings," "Symposium," "Scorner’s Seat," and his Fortean centerpiece, the novella Where Have You Been, Sandaliotis? Most of these narratives connect, in some way, to Charles Fort’s idea of the Super Sargasso Sea, first introduced in The Book of the Damned. Fort occasionally influenced Lafferty, even when the word Fortean does not appear. That’s why "Fall of Pebble-Stones"—which doesn’t mention Fort explicitly—is the most purely Fortean in the group. But more on why in a moment.

In “Pebble-Stones,” Bill Sorel is a feature writer with a reputation for stirring things up. He has just won what he calls “the big red plum,” the chance to compile The Child’s Big What and Why Book. He just has to provide simple but true answers to children’s most puzzling questions, such as “Why does a baseball curve?” and “How do the pebbles get under the eaves?” This is quite unlike the old defition of philosophy: asking questions like a child but giving answers like a lawyer.

Sorel throws pebbles from his nineteenth-floor window while trading theories with his neighbor Etta Mae. She’s full of imaginative, non-scientific, non-philosophical explanations, like lightning-fused sand and even a somebody who makes pebbles appear so Sorel can keep throwing them. Sorel dismisses it all but admits that much of science’s accepted wisdom is equally “kind of doubt.” This is all very Fortean.

Sorel investigates further, he encounters George “Cow-Path” Daylight, a small-town pitcher, and his granddaughter Susie “Corn-Flower.” Cow-Path shows with an onion how the axis of spin, not the direction, determines a baseball’s curve. Susie, however, suggests that pebbles appear because “the pebble angel puts the pebbles directly into the eaves-drop ditch.” Sorel uses this explanation for his book. When rain falls that night, his ledge overflows with pebbles, confirming it. Laughing with the neighborhood cop as they hurl stones into the street, Sorel says, “The pebble angel is showing that he likes the mention.”

Over the weekend, I read a very fun and appropriately untrustworthy book on Fort that I would recommend, Colin Bennett’s The Politics of the Imagination: The Life, Work and Ideas of Charles Fort (2010). Fort, an early 20th-century writer—let’s be generous and call him a researcher—devoted his life to gathering lists of these these anomalies, mocking science for its rejection of outliers and disconfirming data. In The Book of the Damned, Fort fills page after page with wonders, poking and picking at the libido dominandi of the scientists.

"I do not say that the data of the damned should have the same rights as the data of the saved. That would be justice. That would be of the Positive Absolute, and, though the ideal of, a violation of, the very essence of quasi-existence, wherein only to have the appearance of being is to express a preponderance of force one way or another—or inequilibrium, or inconsistency, or injustice. Our acceptance is that the passing away of exclusionism is a phenomenon of the twentieth century: that gods of the twentieth century will sustain our notions be they ever so unwashed and frowsy. But, in our own expressions, we are limited, by the oneness of quasiness, to the very same methods by which orthodoxy established and maintains its now sleek, suave preposterousnesses. At any rate, though we are inspired by an especial subtle essence—or imponderable, I think—that pervades the twentieth century, we have not the superstition that we are offering anything as a positive fact. Rather often we have not the delusion that we're any less superstitious and credulous than any logician, savage, curator, or rustic."

While Fort had quirky things to say about the real Sargasso Sea, one obsessive subject in his work was the Super Sargasso Sea, a hidden, cosmic reservoir where lost objects, creatures, and mysteries gathered before sometimes falling back into our world: frogs, fish, red dust, gelatinous matter, pebbles, and so on. As Fort put it, “I accept that, when there are storms, the damnedest of excluded, excommunicated things—things that are leprous to the faithful—are brought down—from the Super-Sargasso Sea—or from what for convenience we call the Super-Sargasso Sea—which by no means has been taken into full acceptance yet."

And if by damned things, Fort meant all the observations cast out by science, an awful lot of it drew from the Super Sargasso Sea: rains of frogs, lights adrift in the sky, gelatinous objects falling from nowhere. The data of the damned. These are the pebbles Etta Mae’s angel drops into our world. In “Pebble-Stones,” Lafferty reverses the miracle: Fort’s damned is Lafferty’s blessed, holy gift.

“Fall of Pebble-Stones” is straightforwardly Fortean in its premise, if not its twist (Fort hated the regimes of scientific because he thought they were crypto-theological), but Lafferty made an incredible creative leap that goes far beyond that starting point in his other Fortean tales. This is part of his expanded Forteanism, a topic deserving more thought.

Regarding this, at some point Lafferty connected Charles Fort’s idea of the Super Sargasso Sea with the work of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the French Jesuit priest, paleontologist, and philosopher who tried to reconcile evolutionary science with Christian theology. Teilhard imagined evolution as not only a biological process but also a spiritual one, moving creation toward higher levels of consciousness and unity. Central to this was his major idea, the noosphere, a new layer of development surrounding the Earth, arisimg from human thought, culture, and shared mental life.

Just as the geosphere is the realm of matter and the biosphere the realm of life, the noosphere, for Teilhard, was the sphere of collective human consciousness, evolving toward what he called the Omega Point—the eschatological goal of unity and divine fulfillment. Lafferty took this and (sometimes placing it high in the sky or spreading it through the air and a,biemt) used a middle term to connect to to Fort’s Super Sargasso Sea. That middle term? the Jungian concept of the Collective Unconscious.

We see the underlying logic in The Elliptical Grave (1977/1989), where the excavation takes place in the air; we see it in Where Have You Been in Sandaliotis?, where the mirages of Fort's New Lands (1924) combine with the appearance of the land mass and the Fortean Object/weapon in the sky; and we see it strongly at work in "Oh, Whatta You Do When the Well Runs Dry?"

The thought goes something like this: if all human creativity, wit, and inspiration flow from a shared reservoir (the exteriorized collective unconscious), then the depletion of that reservoir leads to collapse. But the collective unconscious is not a closed system. It is a compartment within a larger cosmic reservoir, something like Fort’s Super Sargasso Sea, which can be accessed, merged, and replenished. Therefore, by breaking down barriers and linking the collective unconscious with the broader, exteriorized noospheric flow, creativity can be restored, though now reshaped by the chaotic abundance of the wider cosmic well.

Of course, Lafferty often has more up his sleeve, which makes this story even more fun. November 7th was Lafferty’s birthday. He liked to tell people—though not quite accurately—that he stopped writing on his seventieth, November 7th, 1984, as if that day marked the well running dry. In other words, he made the image of the well’s exhaustion in the story, written over a decade earlier, part of his own biography. But the actual story’s "sky note" ending places its November 7th in the forgotten past, which means the source of all Lafferty’s wild imagination is a pre-birthday in an earlier cycle.

“We haven’t any particular wells or fountains of our own. We draw it from the same unsanitary and common pool.” It’s a great ending.

Some notes on the non-footnote:

Maneuver | From the Footnote | Function | Implication |

1. Metafictional Rupture | "(aw, naw, not a footnote)"; "a twenty-seven-mile-up-in-the-air note" | Breaks the fourth wall: addresses the reader and subverts its own literary form, rejecting the academic distance of a standard footnote.

Establishes a Fortean epistemology: Links the "truth" of the note to the strange, anomalous reality of the Forteans, suggesting that true understanding lies outside conventional, empirical frameworks.

Imitates Charles Fort himself, making notes. | The story's final truth is not subordinate but central. It collapses the boundary between the narrator's world and the reader's, priming the reader to accept the story's logic as applicable to their own reality.

This is the Fortean aim as well. |

2. Temporal Reconfiguration | "...presented — as a convention — as a future account.""Actually it happened in the year 1999 in an era that prevailed a long time ago...""...an earlier cyclical correspondence to our own era." | Shifts the narrative's genre: transforms the story from speculative science fiction (a warning about a potential future) into a historical or archaeological account (an explanation of a definitive past).

Creates cyclical philosophy of time: rejects a linear, progressive view of history in favor of a cyclical model where a past event shapes and corresponds to our present. | The story becomes an etiological myth. It is not an allegory for our world; it is presented as the foundational, causal explanation of our world.

Events are positioned as the origin story for our current state of consciousness. |

3. Foucauldian-Jungian Diagnosis | "...reconstruction in the archaeology of the mind...""...how things became so raunchy down in the well of the world and how ourselves became so raunchy.""We draw it all from the same unsanitary and common pool." | Literalizes a psychological concept: takes Carl Jung's "Collective Unconscious" and treats it as a tangible, physical resource that can be depleted, contaminated, and merged.

Frames the myth as a diagnosis: Uses "archaeology of the mind" to unearth the hidden structure of our modern psyche and explain its fundamental nature.

The exteriorization is Noospheric | Diagnoses modern humanity as universally and inescapably common and unhinged.

Agues that the loss of elitism and curated thought (personified by Irene Komohana's death) was a real event.

The raunchy, chaotic, and shared pool is not an option but our condition. |

Overall Synthesis: The Hermeneutic Key | The entire passage, working in concert. | Performs a metaleptic leap: breaches the boundary between the fictional narrative and the reader's reality, pulling the reader into the story's conclusion. Reframes the entire text: Reveals that the story was not just a story, but an argument about the nature of our own minds. | The footnote is the deeply buried thesis, which is a nice bit of Lafferty humor.

We are not merely readers of a tale; we are the descendants of its outcome, living in the "Post-Intervention Fortean Equilibrium" and drawing our thoughts from that unsanitary and common pool. |