"Magazine Section" (1984?/1985)

- Jon Nelson

- Jan 17

- 10 min read

Updated: Jan 18

“Everybody liked him except those animals, the coons, badgers, and wolverines, those animals that traditionally hate and fear dogs. Then there appeared a wolverine of genius in the neighborhood. In every species, whether wolverine or human or other, about one individual in five million will be an individual of genius. The gifted wolverine got about a hundred other wolverines to assemble. He had to be a genius because the slashing solitary wolverines are lone hunters who hate other wolverines only slightly less than they hate creatures of other species. But he assembled them.”

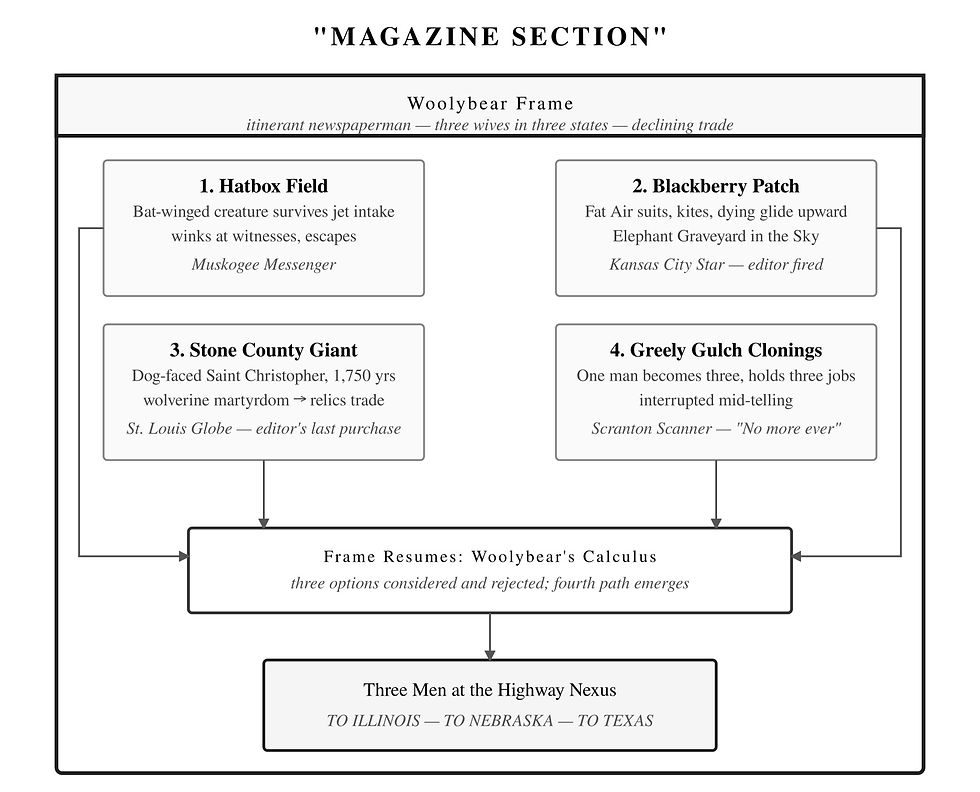

Lafferty would scribble down plot ideas and mark them off once he used them, and sometimes he would put the ideas together to see if anything would happen. The late short story “Magazine Section” reads like a mash-up of set pieces, with associative logic stringing everything together until we reach a scene where the story seems to verify that all the garish, lowercase-t true stories we have been reading did happen. It’s a fun story, but there is an element of melancholy that the old glorious days of the “Magazine Section” are gone, the magazine section being another world that ended in the Lafferty canon. One will no longer open the newspaper to find the old-style magazine pull-out, with its human interest pieces, comics, trivia, and games but something even more limited that looks a little like it. Now that our world has largely abandoned the newspaper as a physical object, the story is even more of a cultural coda. As someone with a deep interest in the history of the newspaper comic strip, I have long been saddened by it.

Near the beginning of the story, we are told that John T. Woolybear looks like a person with comic-strip freckles, the ones with blue circles around. He is a traveling journalist, a newspaper hobo, and specializes in writing garish but true feature stories for Sunday Magazine sections. His first chronicled account details an incident at Hatbox Field in Oklahoma. A small commercial jet engine sucked in a formation of flyers. While four were geese, the leader was a small, bat-winged creature with a human-like face. The bat, a creature that survived the engine intake, scared the heck out of the people who saw it happen, said, “Hot and fast, there’s just no thrill like it,” winked, and flew away, leaving behind a legacy of sightings by residents.

Woolybear’s other reports describe other regional anomalies in the Midwest. In Blackberry Patch, Kansas, a community uses man-carrying kites and inflatable "Fat Air suits" to travel across state lines. Woolybear says these people do not have graveyards but instead glide upward into a secret, paradise-like cloud. That cloud can be found two miles above Kansas City. Another story tells the read about a dog-faced giant in Stone County, Missouri, who might well be the historical Saint Christopher. This giant lived for over seventeen centuries and performed miracles at a local mill before being killed by a pack of wolverines and having his bones sold as holy relics.

As the newspaper industry changes, editors begin to reject Woolybear’s work. They view his style as outdated and absurd. His last try at a feature is about case of cloning in Greely Gulch, Pennsylvania. Woolybear reports on an auditor who discovered that three men were able to hold nine separate jobs by tripling themselves during the workday and merging back into three individuals at night. Despite Woolybear’s confirmation that he personally verified the cloning at an "Outworker Agency," the editor of the Scranton Scanner refuses to publish the piece. This leaves Woolybear unemployed and reflecting on his three estranged wives.

In the final scene, Woolybear experiences the elements of his stories manifest in his own life. After contemplating using the "Fat Air suit" and kite in his possession, he uses the cloning tricks he learned in Pennsylvania. A single small suitcase magically multiplies into three. The story ends with three identical versions of Woolybear standing at a highway junction outside Scranton. Each man carries a suitcase marked for a different state—Illinois, Nebraska, or Texas. He is returning to his three wives.

“Magazine Section” hides its didactic mode behind the sense that the world has lost some of its magic, though there is a didactic element in what it does with St Christhoper. Instead, it uses what I have called palimphanic association for aesthetic effects through layered, overwritten texts. It just happens to be the case that this time Lafferty is doing it with his own texts. One senses there must be some connection between the gremlin of story one and the kite flyers of story two. All the stories deal with the materials of romance and the question of technology. As each text overlaps with the one preceding it, it builds on its prior associations.

Let’s start with Woolybear, whose early-twentieth-century comic-strip appearance links him to the consensus world that has faded. The coda stitches all the stories together through his life as a newspaper hobo. That is the most palimphanic element in the four features in “Magazine Section.” They are a displaced, semi-cohesive autobiography of the narrator, John T. Woolybear. Woolybear has three wives, and the stories give us the pieces to document how he might return to them.

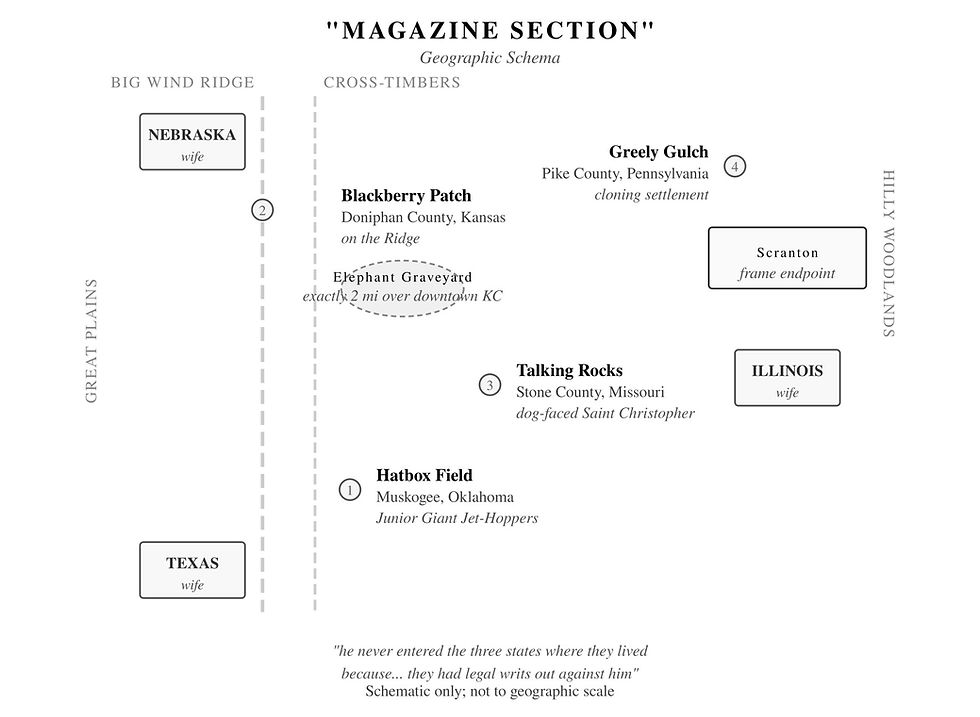

The other palimphanic glue is geography. In the second story, Woolybear describes “Big Wind Ridge,” running from the Texas Gulf Shore through Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, the Dakotas, and into Canada, with prevailing westerly winds that carry “Fat Air” suitors across Missouri into Illinois. This geographic range touches the exact states where Woolybear has his three wives: the Ridge passes through Texas and Nebraska, while the drift pattern deposits travelers in Illinois. When Woolybear opens his suitcase in the final pages, he is physically carrying a Fat Air suit and a man-carrying kite—he is a practitioner of the magic he writes about. The third story, set in Stone County, Missouri, provides a philosophical framework: Saint Christopher, a “Giant” fragmented into thousands of relics so he could be present for all his believers simultaneously. Did Woolybear’s large suitcase belong to St. Christopher?

The abandonment of the old story magic in the “Magazine Section” leads the story into the didactic mode, the other side of the palimphanic in Lafferty. Woolybear's leads have a few rules:

“THEY MUST BE STRANGE, THEY MUST BE OUTRAGEOUS, THEY MUST BE GARISH, and they must be true.”

Chasing down the strange, outrageous, garish, and true takes Woolybear into the story of St. Christopher and some poignant satire of the Catholic Church.

The origins of the legend of St. Christopher could hardly be more obscure. In the Orthodox tradition, he was an early Christian martyr. His cult is attested by an inscription from a church at Chalcedon dated to 452. The earliest surviving Latin Passions date only to the late seventh or early eighth century, and the Greek Passions to even later.

In these texts, Christopher is called Reprevos. He is said to belong to the Cynocephali, the “dog-headed people.” He is recruited as a soldier into the Roman Cohors Marmaritarum. After witnessing the persecution of Christians, he converts to Christianity and is baptized under the name Christopher. He then performs miracles, including one in which his staff sprouts leaves. He converts fellow soldiers and others, endures torture, and is eventually beheaded. His body is buried near a river.

Iconographically in the East, Christopher developed into two main types: one as a military saint and another as a cynocephalus. The earliest known visual representation of the dog-headed St. Christopher appears on a terracotta relief from Vinica (probably before 733), where he is shown as a soldier alongside St. George. Later Byzantine icons and frescoes depict him with a dog’s head, military attire, and his leafy staff.

The Western tradition later popularized the image of St. Christopher as the one most familiar to Catholics and non-Catholics. That is Christopher carrying the Christ Child across a river. At some point, these two traditions influenced each other. That joint motif appears later in Byzantine art, and a well known image (Cyprus, 1745) combines the dog-headed form with the Christ Child and staff. Devotion to Christopher in the East was always fairly limited and never fully integrated into the ranks of Byzantine military saints.

We now come to RAL again. You won't hear much about St. Christopher nowadays. After the Second Vatican Council, St-Christopher was removed from the General Roman Calendar. That happened in 1969 as part of post-Conciliar liturgical reforms. The on-the-ground argument was that the historical evidence for Christopher’s life is insufficient. As part of the liturgical reform, the action did not abolish his sainthood or private devotion to him, but it meant that his feast day was no longer universally celebrated in the official Roman Catholic liturgy and was left to local calendars or popular devotion. What happens to St. Christopher when he is killed by wolverines in “Magazine Section” is an allegory and a staire, with the wolverines being the people who implemented Vatican II.

Lafferty’s St. Christopher vignette is another case in which a lack of Catholic historical knowledge can obscure what is happening in a Lafferty story. The amnesia theme appears in the loss of old-style cartooning (manifest in Woolybear’s freckled face), in lost folkways, in lost genres, and in the fading of garish, outrageous tall-tale telling. And then there is religion.

One hears it said that Lafferty was hostile to Vatican II. That is shorthand and not terribly helpful for understanding Lafferty. Rejecting the implementation of Vatican II is not the same as rejecting Vatican II itself. Had Lafferty really rejected Vatican II, he would be a schismatic and not in communion with the Roman Catholic church. One could not call him both a practicing Roman Catholic in communion with Rome and someone who rejects Vatican II. What did he do? Well, he said that the American Catholic Church was schismatic, not he. He went hard on this one.

What makes it confusing to non-Catholics (I think) is the way the Catholic Magisterium works. There is a Magisterial difference between the Council’s authoritative Magisterial texts and the ways those texts were later interpreted and applied. Vatican II consists of specific constitutions, decrees, and declarations issued by the bishops in union with the pope. The Council took place between 1962-1965. Its implementation took years (it continues to rock the church and is being implemented) and involves pastoral strategies, theological interpretations, disciplinary decisions, violent debates, and cultural adaptations. All this followed Vatican II, but it is how the laity experiences Vatican II.

The equation of experience of the aftermath of the Council with the Council is unfortunate. Well-catechized Catholics know this. It is historical literacy necessary for a thoughtful life in a very big Catholic family. Many changes commonly attributed to Vatican II were not mandated by the Council. They were just pastoral decisions. They arose from readings of its documents, often shaped by historical and cultural pressures. Critiquing those outcomes, therefore, addresses how the Council was implemented, not what it taught.

An aside on this. A friend of mine and her veiled daughters were refused communion recently at a NO Mass because they did not say amen at the reception of host. They did know they were supposed to say this optional formula. They are people who attend the old liturgy. That is not Vatican II. It is a pastoral decision being decided by a Catholic deacon handing the host to the palms of communicants who thinks an emergency indult is the only way to do it, whatever one thinks of the indult. There is nothing in Vatican II about receiving Communion in the hand, which is now the common practice in the U.S. There is also nothing in VII about disrupting the beauty of the Catholic Mass in order to exchange the Sign of Peace. Sacrosanctum Concilium permitted the Mass to be celebrated in the vernacular; it did not mandate that Et cum spiritu tuo be sent the way of the woolly mammoth and replaced universally in the NO with “And with your spirit.” It did not say there had to be a Sign of Peace where people hug, shake hands in the middle of an anamnesis of the Last Supper, and flash the two-finger peace gesture. There is a funny story that Tolkien embarrassed his grandson by refusing to respond with anything other than the old Et cum spiritu tuo. Not only did Tolkien not conform, but he was also loudly non-conforming. I cannot think of one important conservative Catholic artist who did not struggle with this. Had O’Connor not died there would have been stories.

Lafferty put the whole matter this way in a letter to William C. Beuby:

Honest Documents did come out of the Council by the Grace of God. But in the most readily available versions they were dishonestly presented. The commentaries that accompanied them were subtly but strongly anti-Catholic and anti-Papal.

Thus, Lafferty could accept the actual deliverances of Vatican II while still arguing that post-Conciliar implementations exceeded the Council’s intent, obscured its truth, or came into schism with sacred doctrine. His position does not deny the legitimacy of Vatican II; it challenges a particular interpretation or application of it, something theologically coherent and historically common within the Church. But from the outside, it sure might look like waving one's fist at the Council itself.

A parallel distinction sheds light on the St. Christopher section of “Magazine Section”: it is the difference between calling something a myth in the sense of a historical lie and what the Church actually did with St. Christopher. Lafferty does not like it. The Church did not declare Christopher a myth. It removed him from the public liturgical calendar, which was a change in liturgical form. Nevertheless, countless people now claim that “the Church said St. Christopher was a myth.” The Vatican has never said this. What Lafferty saw, instead, was what happened: certain proponents of Modernism, eager to apply historico-critical “PR” to the liturgy, created conditions in which the myth-claim could harden into a kind of consensus reality. In that way, St. Christopher was effectively vaporized from lived Roman Catholicism. There isn't much St. Christopher in the living Catholic imagination, though he is all over older Catholic art.

Lafferty himself was a member of an association for the old Latin liturgy, and these changes wounded and angered him. Of the Church wolverines who took down the real St. Christopher, he was acidic. He said, “Heresy broke into the open with Vatican II.” He called it neo-Arian and anti-papal. He wrote that it was a “Hydra of a Heresy . . . [with] at least ninety-eight other abominable heads.” One of the casualties was St. Christopher, which is what we see in "Magazine Section":

. . . Horace Goodjohn Christopher, a retiring sort of man who seemed to be liked and admired by everybody and everything except the coons and badgers and wolverines. These animals hated him, but dogs loved him, and people liked him.

This is a didactic comment on the real St. Christopher and on the Church as Lafferty understood it. In my view, the St. Christopher allegory is palmphanically connected to the three-in-one motif on which the story concludes, but that would take us far afield.