"Jack Bang's Eyes" (1976/1983)

- Jon Nelson

- Dec 16, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 11

Now we must apply what we have said of the part to the whole living body. For the same relation must hold of the whole of sensation to the whole sentient body as obtains between the part and the part. That which has the capacity of life is not the body which has lost its soul, but that which possesses its soul; seed and fruit are bodies of this kind potentially.The waking state is actuality in the same sense as cutting is the actuality of the axe, or seeing of the eye; but the soul is actuality in the same sense as the faculty of seeing or the faculty of using the instrument. The body, then, is that which exists potentially; but just as the pupil and the faculty of sight constitute an eye, so in the other case the soul and the body constitute a living being. — Aristotle, De Anima (On the Soul), Book II, chapter 1, 412a–412b, trans. J. A. Smith (1911).

And the answer is that we don’t really see with them. We see with something other than our apparent “outer eyes.” The analogy with the ear is close. We hear with our inner ear and not with our grotesque outer ear. Those things on the outside of our heads are for gathering and focusing the sound, it is said; and then the inner ear “hears” that focused sound. That is ridiculous. How could those things on the outsides of our heads gather or focus anything? God put them there for His own reasons and for His own humor, but they haven’t much to do with our hearing. And He also put apparent “outer eyes” in our heads, for His own reasons and for His own humor; and they have only a very little bit to do with our seeing. They have a bit more to do with our seeing than have our outer ears to do with our hearing, but only a bit more. It is possible that those “outer eyes” are not such outrageously inept instruments at all, but only instruments whose purpose we do not understand. It is possible that God is not a complete bungler, but One whose purposes are veiled.

“Jack Bang's Eyes” is a terrific Lafferty story, and I am sorry that I will never own it in the Centipede Press edition. These days, that volume (the one I do not own) commands well over $2,000 on the secondary market. It is a little criminal, given how little Lafferty cared about making a great deal of money. The other night, I was rereading some of his business letters and was struck again by how important it was to him to do what he wanted, rather than anything that would earn him much. As he put it in an essay, he would never cheap-jack it.

After this summary, what I want to focus on is how it reverses Not to Mention Camels (1976) and Lafferty’s theme of noetic darkening. At its simplest, noetic darkening is Lafferty’s technique of making things brighter, more colorful, more festive, even as the character experiencing it becomes increasingly morally blinded. It is the loss of the good of intellect. “Jack Bang's Eyes,” finished two years after Camels, is the reversal of that trope in his work. What it enacts might be called noetic incandescence: a mode far less common in Lafferty, but one that receives its fullest treatment.

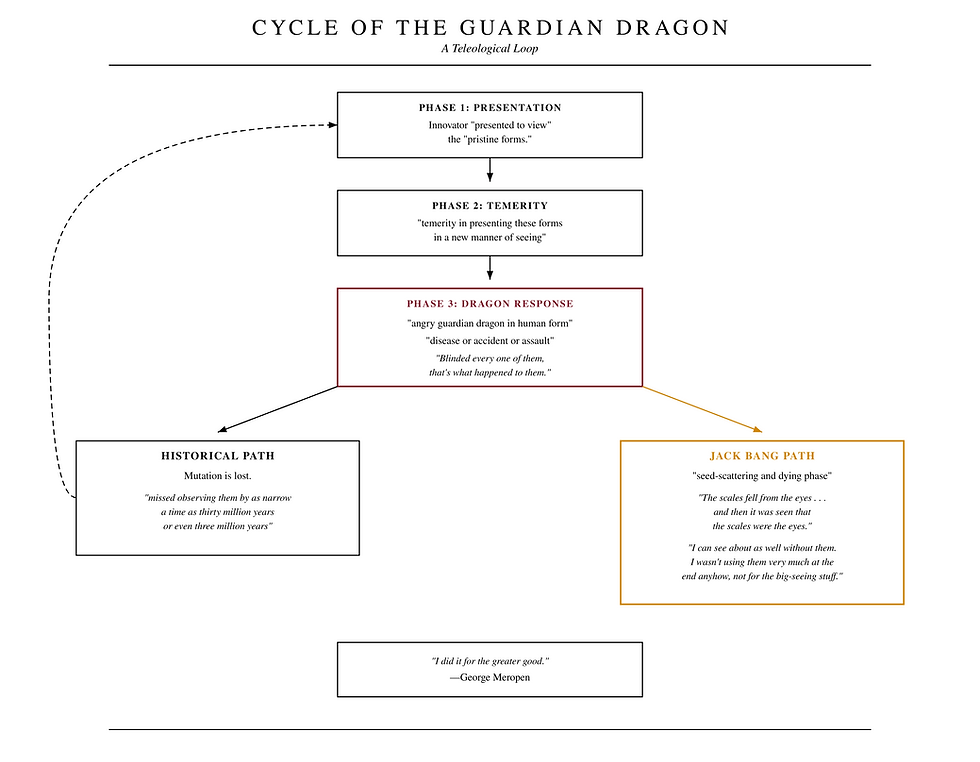

“Jack Bang's Eyes,” like “Ginny Wrapped in the Sun,” is one of Lafferty’s mutation stories, this time centered on a radical mutation in human perception that grants a series of superior visions. The story begins with Lafferty in his historical-exposition mode, explaining that throughout history those who promulgate deep perceptions tend to incur a curse. There is always a faction prepared to take “retribution on anyone who promulgates one of the superior visions,” and that retribution takes the form of physical blinding. Jack Bang, the primary host of the mutation, is a man whose watery vision and failing eyes paradoxically become the vehicle for this new sight. Jack can see humanity in a colorless, schematic form, one that reduces living persons to “great white grub-worms when they move.”

This visual acuity then develops new powers. Jack begins seeing the electrical coronas of people and things, and they are not random. They reveal “flowing psychic equations” and “dazzling topographic configurations” of the person’s entire contents. His sight also grants X-ray penetration, so that Jack can see people at a visceral level, as if they were “something out of an animated technicolor anatomy textbook,” and microscopic magnification down to the molecular level. This talent, what Lafferty calls “multiple-viewpoint-vision,” makes Jack an excellent gambler. He can see through cards and into the sinking hearts of his opponents, though it costs him his pleasure. The enhanced vision may be a gift, but it takes the fun out of poker when you win all the time.

The scientific observation of the mutation is conducted by Lafferty’s recurring character, Doctor Velikov Vonk, who is here the head of the Probability Division of Creative Mutations. He treats the Jack Bang event as a battle to make a beneficial mutation permanent. Vonk notes that “only one mutation in a million is likely to be of benefit,” and he tracks the viability of Jack’s condition through the coin-flipping predictions of one of Lafferty’s most memorable characters, Flip O’Grady, a hot-handed chimp who can affect zones of probability. Over the course of the story, the mutation becomes contagious. It infects those around Jack, including Katherine Hearne, who says that Jack’s new gaze gives her the creeps. It is strange to be observed so thoroughly. Jack’s prominence and success, however, soon bring out the dragon in the form of George Meropen, who threatens him repeatedly.

The climax comes when Jack celebrates his new state, boasting that he will “make a poem to eyes, to my own gloriously exploding eyes.” Meropen, jealous over lost gambling money and over Katherine, says, “You took my girl. You took my money,” and attacks, cutting out Jack’s eyes. Lafferty writes that Jack’s eyes “broke then, and gushed away in two scarlet streams.” Flip O’Grady’s calculations register the failure at once. The odds of the useful mutation’s survival skyrocket to ten billion to one against.

The Lafferty twist is that the personal catastrophe is the mutation’s final, necessary step. Jack says that he “can see about as well without them. I wasn’t using them very much at the end anyhow.” The scientific community realizes that the loss of the physical outer eyes confirms that the superior vision resided in a deeper, internal capacity. Flip O’Grady reports that the odds for a beneficial mutation have rallied and shortened. The blinding turns out to be the required “seed-scattering and dying phase” for the mutation to become transmissible and stable. Doctor Vonk concludes, triumphantly, that they are “coming up to incredibly short odds . . . Victory, Victory! For battlers like us, those are not bad odds at all.”

The allegory Lafferty is working with here is fairly straightforward, so it helps to contrast it with his fuller symbolic system. Velikov Vonk appears in a number of Lafferty stories, including the major story “Boomer Flats.” In Camels, he is one of the few trustworthy characters, existing across that novel’s alternative realities as both Wilcove Fun and Funk. Camels tells, in many ways, the same story that “Jack Bang's Eyes” tells, but it does so as catabasis.

Readers will remember that Camels’ protagonist’s eyes undergo a grotesque symbolic transformation that tracks his movement from an already miserable human being into an artificial cult idol. After a violent attack by Evanhand’s man Mut, his vision changes. Lafferty describes it beginning with the stars, jewels, and pinwheels he sees as he is beaten, an assault that lodges in his eye sockets, leaving him with eyes that are “much brighter, but much more fractured.” From this point on, other characters see his eyes as cracked glass or jewels—“idol-eyes” that mark him as no longer fully human.

In Camels, this visual transformation parallels the protagonist’s shift from Pilgrim Dusmano to Pelion Tuscamondo to Polder Dossman. The jeweled eyes signify his increasing detachment from a living human self and his acceptance of being a manufactured figure. He begins as a manipulator but ends as something manufactured, and one of the ways Lafferty drives the point home is by having him reject his former “live eyes” when he encounters them symbolically embodied in a statuette and orders them destroyed. That act extinguishes the last remnant of his real personality in the service of becoming a media icon. Not for nothing is one of the most memorable images in the novel an eyeball of a child staring up at the protagonist from the ground, set amid the butchered bodies of the child’s family.

I have described Lafferty’s use of noetic darkening as a counterfigurative technique: a way of dramatizing descent into a hell of brightness without meaning. “Jack Bang's Eyes” reverses that trajectory and opens an alternative path. Here, overwhelming light does not darken the intellect but opens onto revelation. Taken literally, Jack’s eye problems could easily be read as symptoms of noetic darkening. Lafferty writes that Jack is dizzy and feverish, surrounded by coruscations and flame. To observers such as George Meropen, the story’s villain, Jack’s condition looks pathological, even dangerous.

As an aside, there is an allusion here that folds into the story’s larger meditation on vision and blindness. Merops is a term Homer uses, usually translated as “mortal” in English versions of the Iliad. Greek scholars disagree about its precise meaning, but Lafferty appears to have an eye-pun in mind: mer- and -op suggesting partial vision, exactly the kind of vision hostile to Jack’s mutation. Meropen’s sight is fragmentary, reductive, defensive. It cannot tolerate what Jack is becoming.

Jack Bang’s eyes are not organs of partial vision, and that fact goes to the heart of the allegory. Jack awakens into a vision of reality that peels back ontology itself: psychic equations, moral signatures, sanctification. In Camels, there is very little of this. Lafferty spends that novel systematically erasing it. But Jack’s sight is attuned to good and evil. He sees the sour taste of defeat at the poker table, the hidden flaws in crockery, the moral weight of ordinary objects. What in Camels is noetic darkening becomes here a recognitive instrument, one that propels ascent toward something that would, if not halted, culminate in divine vision, which is another way of saying the Beatific Vision. “Jack Bang's Eyes” is about terrifying clarity.

This difference becomes especially clear in the story’s treatment of intellect and community. In noetic darkening, the intellect collapses under overload and gives way either to the dumbly animalistic or to the desacramentalized machine—two forms of fallenness in Lafferty’s moral universe. Lafferty has some fun with this by alluding to Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1896), who argued that the blind spot in the eye is evidence of poor design and, by implication, an argument against design itself. Darwin went further, writing in Origin of Species (1859),

To suppose that the eye, with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I confess, absurd in the highest degree… The difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could have been formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, should not be considered subversive of the theory.

Against this backdrop, Jack’s vision is neither defective nor accidental. It is excessive, morally discriminating, and ultimately intolerable to a world organized around partial sight

In both Camels and “Jack Bang's Eyes,” the eye becomes a test case for faith. Camels makes an apophatic argument. It engulfs the reader in darkness in order to make its point. “Jack Bang's Eyes,” by contrast, argues in positive terms, placing it within the tradition of mystical “divine darkness,” where the saintly figure often appears foolish because he has passed beyond ordinary cognition into direct contact with truth. Jack Bang becomes one of Lafferty’s strange saints, having undergone a martyr-like ordeal at the hands of the dragon, George Meropen. The next time I reread Camels and find myself overwhelmed by its despair, I expect I will stop and turn instead to “Jack Bang's Eyes.”