"Entire and Perfect Chrysolite" (1968/1970)

- Jon Nelson

- Dec 18, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 21, 2025

The chrysolite of Ethiopia cannot compare with it, nor can it be valued in pure gold. Where then does wisdom come from? And where is the place of understanding? It is hidden from the eyes of all living, and concealed from the birds of the air. — Job 28:19–21

But in another visible world, completely unrelated to the first and occupying absolutely a different space (but both occupying total space), were the green swamps of Africa . . .

The Elliptical Grave (1989) is one of Lafferty’s least read and least understood books, yet it is one of my favorite Lafferty novels. As a novel it is not successful, but, as I have said more than once, I do not think Lafferty wrote novels. When he defined his terms, he stipulated what he meant by this, even if in passing he would use the word “novel” when referring to his longer-form fiction. This is both like and unlike the slow student who refers to The Odyssey as a novel. It is like this because the poor kid does not have ideas to work with, so everything long and fictional becomes a novel. It is unlike it because Lafferty is informed, and he is really speaking to the reader who lacks the category set needed to talk about Lafferty. So he uses shorthand, unless you catch him in his essays.

The Elliptical Grave succeeds in pushing many of his ideas about as far out as he could take them and still get safely back to shore, like a swimmer who ventures far into the gulf, something a character of his does, one he based on Job. When reading The Elliptical Grave, one looks at Lafferty as one looks at the man in Stevie Smith’s famous poem, but with a reversal. What appears to be drowning to many readers is Lafferty waving. (As a side note, both the Smith and Lafferty papers are housed at Tulsa. As a Brit lit. person, a highlight of doing a hobby project there is the Smith archive and meeting people who are doing work on the one-of-a-kind Smith, who is also unique, eccentric, and unconforming.)

One of the areas where Lafferty goes deepest in The Elliptical Grave is the nature of the ambient, a term that Lafferty readers encounter often in his fiction. In my reading of Lafferty as a whole, I think of the short stories as taking place in the ambient, into which the oceanic passes. When the word ambient appears, oceanic and water imagery are likely to follow. So how does the ambient work in The Elliptical Grave?

The first thing to note is that the ambient in Lafferty is always stratified, even when it appears transparent. Lafferty creates his concept because he needs a name for this interaction zone. In The Elliptical Grave, Lafferty imagines the ambient an excavatable medium rather than empty space. It has three concentric layers that surround and permeate the book’s central expedition site. The lowest layer is the Earth. The book describes this ground as musical and speaking, saturated with the residue culture, memory, and vitality, all the fragments that we can perceive, even if we are poor interpreters of them. This is the spolia out of which Lafferty so often builds. It is allusion stuff.

In other words, it is soil, what the book calls the solum euphoricum of the White Goat Valley. This soil exhales the scent of Mentha euphorica, the “simple secret of Paradise,” and harbors buried beings who do not decay but are ready-to-hand as usable, semi-living presences. Creatures such as Il Trol and the Neanderthals pass through it as if it were water. The governing idea is that even at its most basic level, the ambient as is a living, resonant substance rather than inert matter.

Then there is a layer above this that Lafferty calls the Haunted Air. It is an inhabited, recording medium extending roughly thirty meters upward. Nothing that occurs in the Haunted Air is ever erased, although events may fade over centuries, forming anomalous clumps, penned-off zones, and weir-dams that regulate its flow. Excavation into this part of the ambient is not as simple as digging up spolia, because it is more than mechanical. It requires performative and imaginative acts. It draws on the living person. In the novel, we see this repeatedly. We see it when Joseph Abramswell beats on a hollow log to startle invisible occupants into revealing themselves.

The Haunted Air is really and truly haunted. It contains ghosts, ghost-trees that can be dated by rings, balloon-like grumpus fish, and lingering bioscopic dreams that replay violent chases in living color and become part of the book’s mystery plot, stuff that can fall to earth the way frogs rain down in Charles Fort.

Above this layer begins the Noosphere. In The Elliptical Grave, it appears as a cooler, blue-tinged zone of rationality and speculation, populated by mind-fishes, air-snakes of thought, and amphibian philosophies. Characters reach it by balloon, and it is structured by visible intellectual patterns rather than by physical matter.

Lafferty turns this, the richest topography of the ambient in his work, into a specific place and gives it a name: the Valley of the White Goat Illusion in Calabria. It is an elliptical, time-bent landscape governed by an alternate geometry, one in which events do not occur according to conventional terms. Although the sea lies kilometers away, a fluid sea-medium somehow fills the valley, audibly breaking against castle foundations at night.

When the novel reaches its major crisis and the Pavilion at the valley’s center enters stasis, it seals off a separate ambient entirely. The outside cosmos vanishes, the air grows ancient and stale, and the ambient becomes grave, coffin, cocoon, and ark. These conditions are meant, one hopes, to nourish the inhabitants while inducing mutation. But space is also hostile. It is inhabited by venomous, politically militant Stoicheio and saturated with projected dread, darkness, and sensations of burial imposed by the occupants themselves. Elsewhere in his work, the ambient is a war zone for factions outside the fourth mansion.

All of this is extreme Lafferty and very strange. In its fullest form, the ambient resembles a deep-sea archaeological site, dense, pressurized, and alive with floating remnants of history and thought. Within it, the characters, sealed inside a kind of diving bell in the form of the Pavilion, wait for transformation under the accumulated weight of time. Every one of them is positioned as the reader is at the end of Past Master (1968). Every one of them is potentially a Fred Foley, poised on the verge of the fourth mansion.

Which brings me to “Entire and Perfect Chrysolite,” one of Lafferty’s better-known stories, largely because it appeared during his great Orbit run and was collected in both Strange Doings (1972) and Lafferty in Orbit (1991). It is a story that calls for a much deeper interpretation than I will give it here, with several layers of allusive play at work. I have seen people point out, for example, that the title comes from Othello, but without explaining how the allusion bears on Desdemona, or why that marriage might matter for the marriage of the story’s main character and his wife. I have also not seen anyone note that Shakespeare mentions the phrase only because it appears in Job, and that Job invokes chrysolite because it is a treasure of Ethiopia, in the midst of reflecting on the nature of wisdom. That context is precisely what makes “entire and perfect chrysolite” so deeply ironic in Shakespeare, and all of this is something Lafferty would have known. I have even seen someone online complain that the title is needlessly arty, as if Lafferty were indulging in pretty talk for no reason. I am not sure that person got past the bouncer.

Beyond these and other verbal games in the story, I mention it here because it is important for thinking through some difficult topics in Lafferty. Anyone who wants to consider how Lafferty handles ethnos ought to read it.

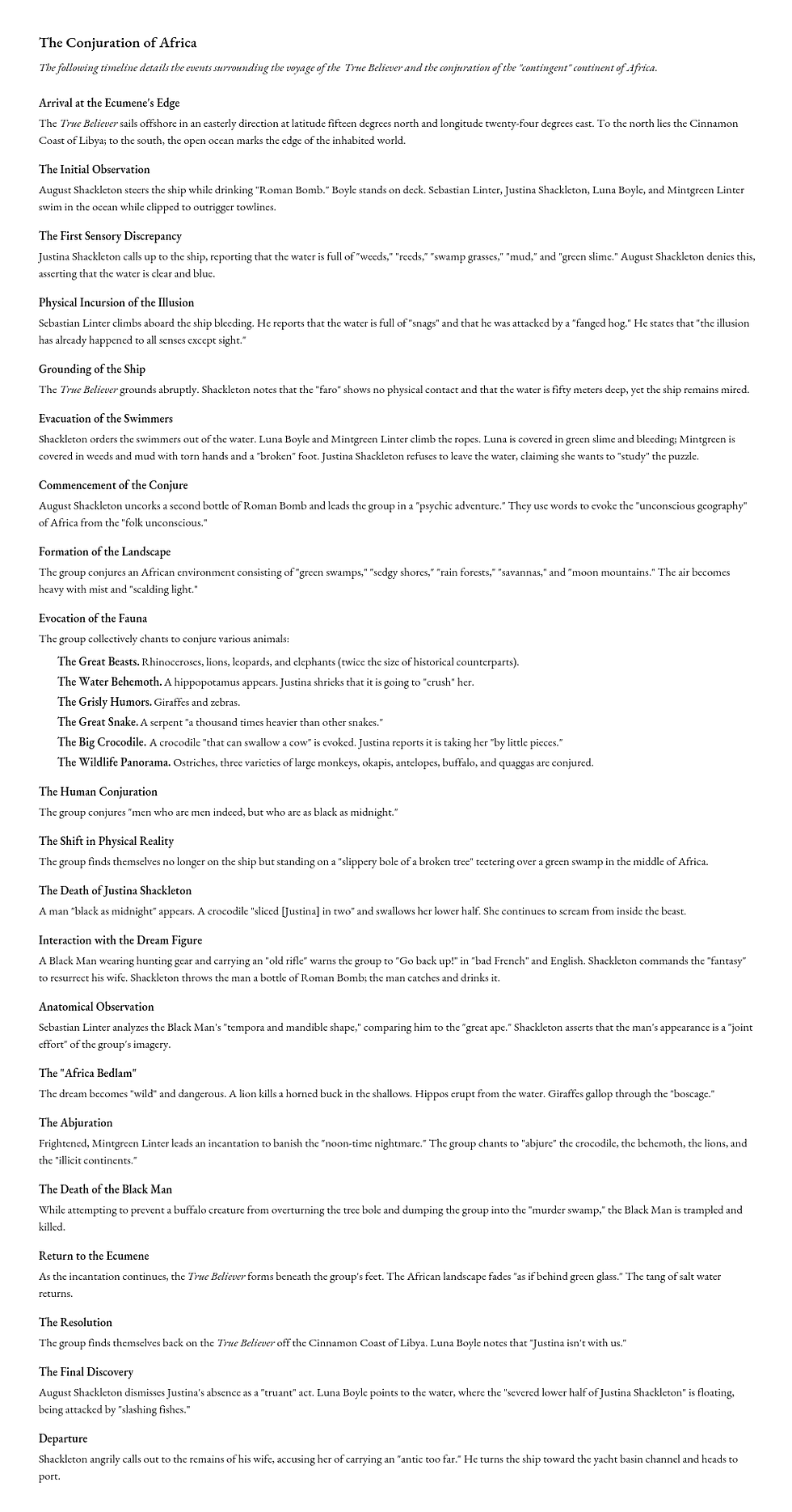

Although Lafferty clearly intends the story as a meditation on the ambient and the oceanic, in 2025 it also invites a reading informed by work in post-colonial studies and related fields. It is, unavoidably, about matters such as whiteness and the norms of not noticing. It seems to me that Lafferty, if not unaware of this dimension of the story, as suggested by his fantasy of the Black man, nevertheless says more than he consciously intends. I will include a diagram at the end of this post to show what I mean, since I am not going to walk through that argument here. Instead, after a brief summary, I will say a few words about how this story represents an early stage in Lafferty’s thinking about the ambient and the oceanic, ideas that reach their fullest articulation in the later novels.

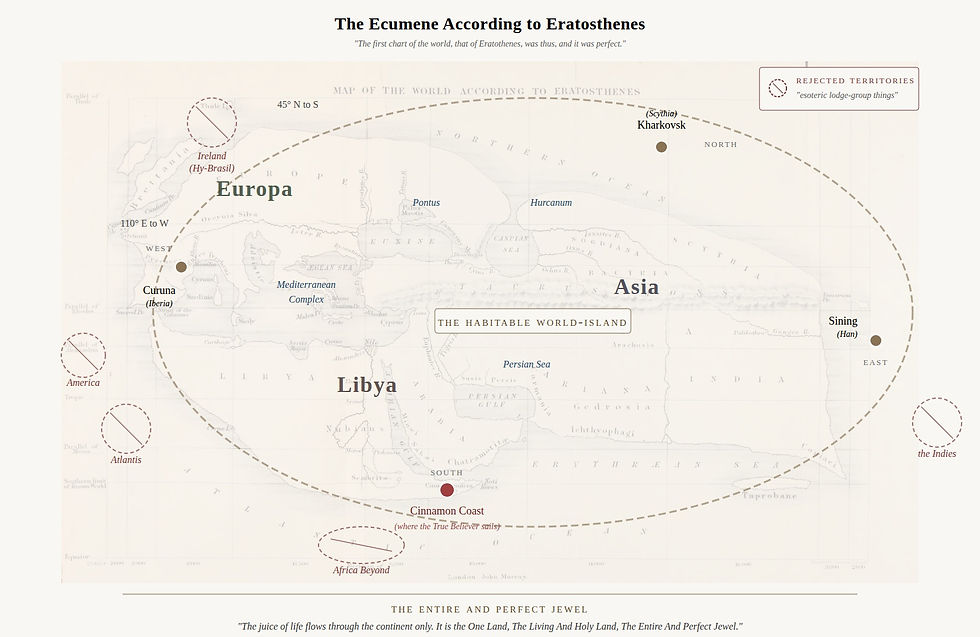

The story opens with an excerpt describing “Exaltation Philosophy,” an ideology that holds that the ecumene, a tripartite world-island consisting of Europa, Asia, and Libya, is the only rational and physical reality. Lafferty takes this concept from classical antiquity and turns it into one of his bad utopias. Within the ecumene, geography is said to be an extension of the perfect thought of the Maker, which it is not, and any suggestion of further lands such as Africa or America is dismissed as a product of the cultish under-mind. The adherents of this philosophy seek “height,” not “depth,” imagining the habitable world-island as a single eye in the head that must remain unmarred by the outré fauna of tortured imagination.

Lafferty’s point, of course, is that a single eye lacks perspective. He also knows that in classical Greek and Latin the same word can be used for both height and depth, hýpsos in Greek and alta in Latin. Unlike the ancients, the moderns of his ecumene, who function as Flatland counterparts, have lost the conceptual language needed to grasp this ambiguity, even though they retain the word ecumene itself.

The story’s characters are a group of travelers aboard the ship True Believer, which sets out to test ontological boundaries by sailing along the southernmost edge of the ecumene, off the Cinnamon Coast of Libya. While most of the men drink Roman Bomb and Green Canary on deck, their wives swim in what should be clear blue water. The experiment, described as a children’s antic meant to call up inner spirits and lands, proves wildly effective. It precipitates a collision of realities. The swimmers report green slime and swamp grasses in the depths of the ocean, even as the men insist that the water remains clear and bright, like living, moving glass.

The act of conjuration next forces an overlapping of realities. The True Believer is replaced by the slippery bole of a broken tree hanging over a green swamp. The ecumene thins, and a mythologized but very real Africa begins to appear. The group presses on, continuing to evoke what they call “contingent Africa,” summoning creatures that the main character insists are caricatures and projections drawn from the individual minds of the party. Lafferty writes beautifully and dangerously about exoticized fauna. Then a “man black as midnight” appears. He warns them that the place is real and that this is death. The travelers dismiss him as a dream figure, a joint production of their collective imagination, refusing to acknowledge his autonomy even as the continental ambient turns lethal.

Justina Shackleton, the wife of Arthur, the main character, and the person in the story attuned to the ambient from the beginning, is sliced in two by a giant crocodile. Her husband responds by laughing nervously, treating her severed, screaming body as a typical product of her imagination, an outré joke. The African bedlam rises to a crescendo of fast-moving color and animal stench. Only then does the group become afraid. Frightened by the howling chaos, they perform a formal abjuration, chanting to seal off the unsettling presences, making the “illicit continents fade” and the “noon-time nightmare pass.”

They find themselves once again aboard their ship in the ecumene. The story closes with the apparent restoration of the perfect world, as the True Believer returns to the clear blue waters off the Libyan coast. The world is once again a whole and perfect jewel, a bright noon-time realm in which the under-mind has been safely put back in its box. There is, however, a problem. Justina is missing from the ship. Her severed lower half floats in the water, her viscera being attacked by slashing fish. August Shackleton is amused and dismissive, treating this too as an instance of his wife’s poor taste.

It is no surprise that this is prime Lafferty symbolism. The ocean functions as both a literal and a metaphorical threshold to the vast unconscious geography of the under-mind, as it does throughout his work. While Exaltation Philosophy treats the world as a single eye in the head, a sterile rational surface that rejects depth in favor of height, the sea is where the collective unconscious and its illicit continents and black legends are buried. The ecumene’s sea is too full. As in the ancient world, the inhabited land is encircled by the world ocean. This condition could not be further from the drained oceanic well of “Oh Whatta You Do When the Well Runs Dry?” Here we find repressed archetypes and outré fauna that the characters, without understanding what they are summoning, invite into the ecumene. What follows is the beginning of the end. These perfect little worlds never fare well in Lafferty, whether they take the form of the golden bowl in Fourth Mansions or the Golden Orb of Astrobe in Past Master.

As in Lafferty’s later, more obscure work, the ambient here solves a formal problem. It becomes a screen on which Lafferty can physicalize psychic states. In the story, it is described as a rhapsody or panorama that exists as a spatial overlap. It is said to be “completely unrelated to the first and occupying absolutely a different space (but both occupying total space),” a formulation that suggests the rational world is haunted by the imaginal.

In this sense, the story presents an Urphänomen of the ambient, one that becomes a key to understanding what unfolds in the final major novels. It is therefore a good place to begin when thinking about how Lafferty starts to complexify the ambient in the early 1970s, before gradually moving away from the metaphor in works such as Serpent’s Egg (1987), East of Laughter (1988), and Sinbad: The 13th Voyage (1989) By that point, he seems to have known that he had taken the ambient as far as it could go in the books he wrote in the mid to late seventies, including the unpublished The Iron Tongue of Midnight and the improbably published The Elliptical Grave. That latter book appeared only because Lafferty told Dan Knight it was his least publishable work, and Dan Knight had something to prove.