"Adam Had Three Brothers" (1959/1960)

- Jon Nelson

- 4 hours ago

- 6 min read

I began to try to write in about 1959 and went a year or so before my first sale . . . My life has been mostly interior and that interior very shallow. . . I am forever a Catholic, a bachelor, a political independent, a lone badger (lone wolves are a legend, they are always in groups, but even the bachelor badger digs himself a hole and spends most of his time in it). So it stands. There isn't much of a biography. Most of my life I forgot to live. — letter to Damon Knight, September 10, 1972.

In the years before Lafferty started writing seriously, he spent three weeks in New York on his own. “Adam Had Three Brothers” is one of the few stories that makes me wonder what he took from that New York experience, because it drops place-signals that read as New York City: Marine Park (surely Brooklyn’s Marine Park) and the Jamaica track, presumably the historical Jamaica Race Course. The track shuttered before Lafferty wrote the story and, though it was supposed to reopen in 1959, never did. The story reads as our New York City, except for that one group. Lafferty writes,

In the town there are many races living, each in its own enclave . . . Its geographers say that it has more Italians than Rome, more Irish than Dublin, more Jews than Israel, more Armenians than Yerevan. But this overlooks the most important race of all . . . it has more Rrequesenians than any town in the world. There are more than a hundred of them.

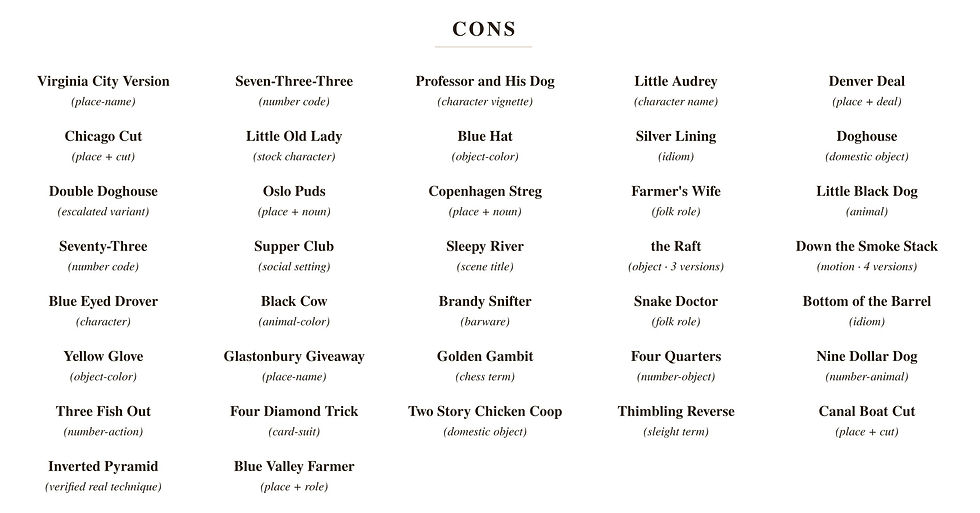

In this first story about the Wrecks, we learn that they are a small racial group not descended from Adam. That places them outside the judgment of Genesis 3—that man must toil for a living. The plot chiefly follows Catherine O’Conneley, a Wreck who supports herself through a series of swindles. She meets Mazuma O’Shaughnessy, a young man who shows a mastery of her “Inverted Pyramid.” He says,

I learned it in my cradle. The Inverted Pyramid . . . Very good. You pick them nice for a little girl. But isn't that a lot of work for no more than a hatful of money? . . . Take my word for it and share my secret with me and give up this penny ante stuff.

He then proposes indirectly. She accepts. After their marriage, the pair travels the world, conning whomever they please, until Mazuma suggests that they settle down. There are comic set pieces along the way. One moment, however, is foreboding: Mazuma lets slip an unguarded remark about a plowman. Cathrine brushes it off, and soon the two have three gifted Wreck children and a happy domestic life. Then the bottom falls out. Mazuma says that he wants to earn an honest living. Catherine faints at this decisive proof that Mazuma is an Adamite rather than a Wreck. She leaves him. The story ends with the children raised as sad, slow Adamites.

The bottom had fallen out of the world indeed. The three unsolvable problems of the Greeks were squaring the circle, trisecting the angle, and re-bottoming the world. They cannot be done . . . One is a professor of mathematics . . . and the oldest one is a senator from a state that I despise.

One becomes a professor; another, a senator; but all Adamites are disappointments. Catherine never quite lives down her youthful indiscretion.

This was one of the first Lafferty stories I read, and it remains one of my favorites. There is much here about how Lafferty thinks about ethnos and about coding—sometimes in ways that look generous, sometimes in ways that are strategically displaced (Jews and Gypsys). I want to set that aside and name two possible readings. They exclude each other. The story’s success depends in part on keeping the two readings in suspension.

Most readers seem to accept the first reading at face value. The storyworld is a tall tale, a fantasy, so one accepts its premises the way one accepts the appearance of Pan in The Wind in the Willows and does not ask why the narrator sounds so much himself like a con artist. Read as “in-universe facts are the facts," "Adam Had Three Brothers" asks the reader to buy magic beans: a literal branch-line off Genesis. The Wrecks are "not even children of Adam," and an "old baked tablet . . . eight thousand years old . . . gives the true story of their origin. Adam had three brothers: Etienne, Yancy, and Rreq.” The narrator gives this the force of Mosaic law: the Wrecks, "not being of the same recension, they are not under the same curse to work . . . So they do not." On this first reading, the Wrecks really are exempt. It belongs to the primordial history of the storyworld:

Adam had three brothers: Etienne, Yancy, and Rreq . . . They have never intermarried with the children of Adam except once. And not being of the same recension they are not under the same curse to work for a living. So they do not . . . Instead they batten on the children of Adam by clever devices that are known in police court as swindles.

The other reading I have in mind says, "Hold up a moment." The story presents a population of con men and con women (with more men than women; note the uncles' last names if you want a clue to how Wreckville society really works), and it gives these scoundrels a mythology about themselves. Why be so cautious and suspicious? Because they are Wrecks. Lafferty may be running the old Adam Had Three Brothers con on us as readers.

Consider a few pieces of textual evidence. We are told of Wreckville that “its geographers say” the town has “more Italians than Rome, more Irish than Dublin . . .” Does it refer to ordinary geographers, or to Wreck geographers—people no doubt eager to sell you a map? The story is full of mock expertise and comic exaggeration, and it positions the reader make a decision about the story being told. One may treat “the true story of their origin” as a Wreck game or as a real origin. In the second case, all you have to do is trust Willy McGilley/McGilly and add a few footnotes to Genesis. But I would point out that his 8,000-year-old tablet “made of straw and pressed sheep dung.” We have idioms for things made of straw and things full of shit. Perhaps ask oneself as a reader, is Lafferty running the Adam Had Three Brothers con on me? Again, the story works both ways at once: credulity and suspicion.

Finally, the story has Lafferty’s first use of the term recension. First instances of major ideas are significant in Lafferty because he builds on them in later work, and they blur in hindsight because Lafferty complexifies. The more time you spend with Lafferty, the more baroque you see him to be. Something like this happened with Epikt, where "Ktistec" had a story-specific meaning about remembering the name of Chicago. That was Epikt's first appearance. Then it attracted great richness.

In "Adam Had Three Brothers," recension is used as if it meant race, or primordial race. The Wrecks are said to be not of the same recension. On a suspicious reading, Wreck is a literal recension: Wrecks have edited themselves into Genesis as descendants of Rreq. They have rewritten the primordial history of Genesis 1-11. When the narrator calls them a different recension, there is a pun. That fits the con-reading. The first use of recension in Lafferty is story-specific verbal play, as is the word Ktistec. Just as Ktistec expands in his imagination, recension takes on meanings I’ve discussed in other posts.

I’ll wrap up by saying that there are interesting points to be made about the theology of the story, from both credulous and suspicious readings, just as there are about how Lafferty uses the three Greek problems—the three classical constructions impossible to solve with a straightedge and compass: trisecting an arbitrary angle, squaring the circle (constructing a square with the same area as a given circle), and doubling the cube (constructing a cube with twice the volume of a given cube). Lafferty replaces the third, the doubling of the cube, with the “rebottoming” of the world. Already in 1959, he recognized that he was writing about the impossibility of rebottoming a world once it ended. Although person in scale (a World 7), "Adam Had Three Brothers" might be his first day-after-the-world-ended story.