"What's the Name of That Town?" (1964) and Little Willy

- Jon Nelson

- Aug 18, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 18, 2025

Today, something brief on doggerel, memory, and “What’s the Name of That Town?”—one of Lafferty’s best Institute stories. It’s a farce, yes, but also a meditation on what happens when cultural memory breaks down.

Lafferty’s poetry deserves more attention than it gets. Often dismissed as doggerel, it’s something more subtle—work that pretends to be simple but usually isn't. That he cared deeply about poetry is clear from a folder of unpublished translations. He took on these works not only for love but as a way to sharpen his feel for language while studying foreign tongues on his own.

Open that underread folder in the Tulsa archive that contains Vogelsprachekund, and you’ll find a lively mix, a polyglot aviary. His take on Rubén Darío’s “Sonatina” dances with toy-like rhythms and a hint of fairy-tale sorrow. It doesn’t mock modernismo’s shimmer but steadies it with folksong. His Villon stays true to the beat of the balade, while the refrain (“I know all things except myself”) lands with full force. Even Goethe bends to the Lafferty style but stays Goethe: “The Fisher” keeps its spell, and “Erlkönig” charges forward with urgency.

Classical sources in his hands appear without stiffness. Horace’s odes are conversational, prayers and toasts expressed as a philosophy of moderation—health, composure, and the music of the lyre. Italian lyricism is a natural medium for Lafferty, with Tasso’s cosmic love rendered into clear, workable English. Lafferty looks outward as well, adapting Olavo Bilac’s Brazilian serenade into bright simplicity. With Heine’s “Lorelei,” Lafferty turns his attention to enchantment, which for him is grave and haunting, as it often is in his fiction, its lull matched by a severe undertow; with Verlaine’s “Il pleure dans mon cœur,” his choices as a translator shift to ones of quiet, pluvial melancholy.

The cumulative effect is not of casual exercises but of disciplined experiments conducted before he turned seriously to writing fiction. It is the workshop behind the doggerel his readers know about from the short stories, the epigraphs, poetry collections, and Space Chantey (1968).

In Lafferty’s fiction, the strange logics that define his worlds often concentrate in snatches of poetry. These lines may show up as epigraphs or embedded poems—sometimes within the story itself, sometimes outside it. They’re short, often rollicking, and usually tightly packed.

The best definition of doggerel I know describes it as poetry that fails to reach the associative richness of true poetry. Its rhythms are forced; its rhymes clobbering. But with Lafferty, that doggerel pressure is part of the design. His fiction carries the weight of the associative work, while the poetry—placed beside or inside the stories—moves beyond doggerel because of the juxtaposition. His doggerel exaggerates simplicity to throw the fiction’s complexity into relief. Read one way, it’s just doggerel. Read another, it’s a tether to the story’s deeper structures, a counterpoint that only makes sense when seen in that frame. Few writers connect the two so tightly. And it does something to make the lines of doggerel poetic by association with the fiction.

Not all of his verse is like that. Some of it is just really damn good doggerel. And some of it really is poetry. So let’s take a look at a few of Lafferty’s best.

But first, a quick summary of "What’s the Name of That Town?" to give you the context for how the “Little Willy” verses support the story’s meditation on historical amnesia.

Institute head Gregory Smirnov and the Institute’s Ktistec machine, Epiktistes, conduct an experiment to uncover something that has been completely erased from human memory. As Epikt churns through millions of fragments, each a clue pointing to a missing piece of history, the Institute staff (including Valery Mok, Charles Cogsworth, Glasser, and Aloysius Shiplap) eagerly awaits a revelation. It’s a gathering fueled by Tosher’s Gin. Taking on the role of the detective who explains why the dog that didn’t bark is important, Epikt shares “items,” culminating in an outlandish claim that a massive American city was destroyed in 1980 and then globally forgotten. Though the Institute members dismiss the idea as one of Epikt’s pranks, the story shows that the past was overwritten—and that Gregory Smirnov’s own invention was used to make everyone forget.

One of the minor casualties of this mnemonic event was a genre of largely forgotten doggerel that Lafferty seemed to have really liked: Little Willy verses. In the story, one of the items Epikt draws attention to is them.

“Item. Why, when the gruesome Little Willy verses were revived among sub-teenagers in the early nineteen-eighties, were they concerned almost entirely with chewing gum? In their Australian and British homelands six decades before, they were concerned with everything. But here we have gruesome verses about forty-nine different flavors of gum. As for instance, Little Willy mixed his gum with bits of Baby’s cerebrumand Papa’s blood for JuicyFruit. Mother said, ‘Oh Will, don’t duit. ‘I’d think it would give too high a flavor to the gum,’said Glasser.”

In this story, a minor gag transforms into a parable about historical memory. The macabre Little Willy rhymes get tangled up with Charles Wrigley—the gum baron who once owned the Cubs—and the ballpark that still bears his name. This small part of the story peaks when Epikt cannot quite get the historical facts straight.

“Loop? Cubs?” giggled Valery. “Those words are almost as funny as Chicago. How do you make them up, Epikt?” “In popular capsule impression Chicago was the chewing-gum capital of the world. The leader in this manufacture was a man named—as well as I can reconstruct it—Wiggly. Children somehow found the echoes of the gruesome destruction of Chicago and tied it in with this capsule impression to produce the bloody Little Willy verses about chewing gum.” “Epikt, you top yourself,” said Shiplap, “if anything could top an invention as funny as Chicago.”

So here we have hermeneutic comedy when information relevant to interpretation isn’t available—history at its wiggliest.

So what were the Little Willie verses, and did they ever become a real, living tradition among kids? That’s hard to say. As far as I know, there’s nothing like Iona and Peter Opie’s The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren for the United States—no deep record of what American kids actually chanted or passed around. Did the Little Willy tradition ever take root in American culture, or was it just something Lafferty imagined? I don’t know. That might be a question for someone in American Studies.

Published in 1959, The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren was a landmark survey of children’s living folklore, based on fieldwork and correspondence with schools across Britain. It documented the rich, strange, self-sustaining culture of the playground—counting-out rhymes, skipping and ball games, “truce terms,” taunts and taboo words, secret signals, superstitions, and informal rules—showing how these traditions spread and evolve largely outside adult influence. In making the argument, the Opies showed that children are active custodians of a resilient oral culture, one that crosses class and region and refreshes itself with each generation. Something like this is at play in Lafferty’s use of the Little Willy tradition, though it's complicated by the fact that Little Willy verses come from print culture. What Epikt doesn’t mention is that the form itself owes a debt to print, an origin that sets it apart from the oral traditions the Opies describe.

My copy of Lafferty's Laughing Kelly and Other Verses (1983), which includes Lafferty’s Little Willy verses, has a fun handwritten inscription on the front.

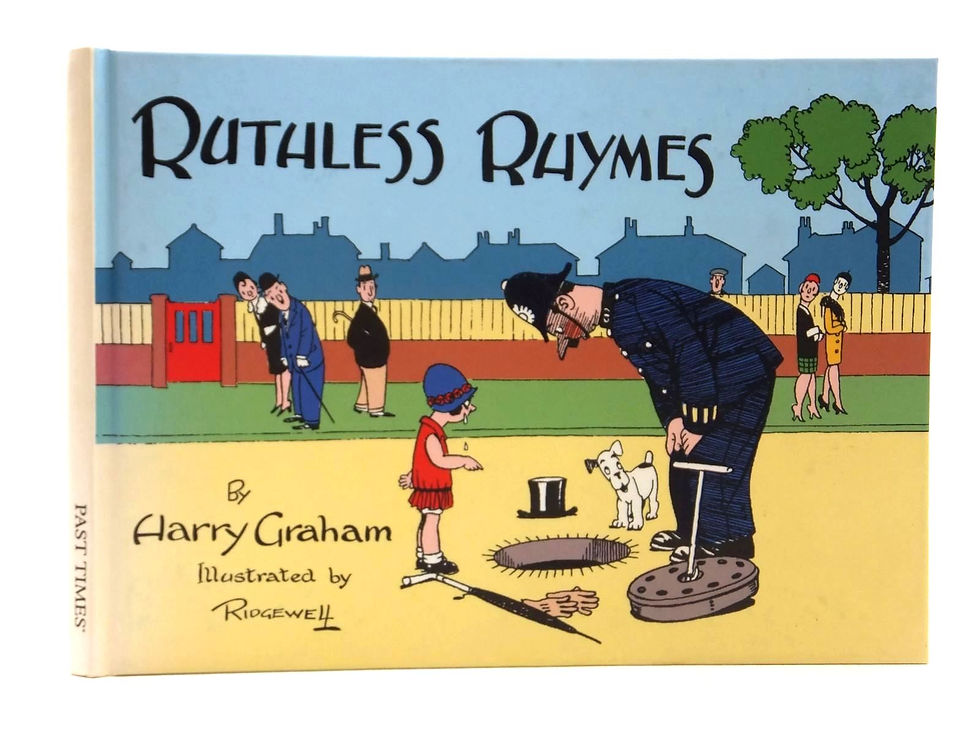

“Little Willie” verses are short, darkly humorous poems built in quatrains. They center on a mischievous child who meets a grisly end or causes one, with the final line delivering a deadpan twist or clever pun. This morbid yet playful form emerged in the late 1890s and is most often linked to Harry Graham (1874–1936). Under the pen name “Col. D. Streamer,” Graham’s Ruthless Rhymes for Heartless Homes helped define and popularize the style.

Educated at Eton and Sandhurst, Graham served in the Coldstream Guards and saw action in the Boer War. He later became aide-de-camp to the Earl of Minto, Canada’s Governor-General, before dedicating himself to writing. In his later years, he gained recognition as a lyricist for operettas and musical comedies. He died in London in 1936.

Here are Lafferty’s brilliantly macabre Little Willy verses, surely the peak of the form:

These are Little Willy verses: Murders, maimings, hacks and hearses. All who meet them want to do some; There’s no way they won’t be gruesome. Little Will with gasoline Soaked his sister Imogene; Poured some more on her and lit it. Mother said, “Oh, Willy, quit it!” Little Willy from the shore Dumped into the reservoir One hundred tons of arsenic. “It’s not the money,” others said, “It’s that the water tastes so funny.” Little Willy, scalpel-smart, Cut out a little playmate's heart. It seemed an eerie undertaking. "I need it for a man I'm making." Willy shot his uncle dead, Removed and then he trimmed his head, Made of it a drinking cup. "Bottoms," Willy chortled, “Up!” Little Willy had The Bomb. Had his finger on the button." Are you listening, Moscow Chum? Are you listening, E. F. Hutton?" Willy, dulling his remorses, Hired four span of wooly horses, Tied them to his friend with stitches, Double-knots and diamond hitches, Flogged the beasts with zest and art, Tore the howling kids apart. Said the mother, and it hurt her, "Willy's getting by with murder." Little Willy oped the ventrals Of his friend, and spread his entrails, Studied all their loops and portions. “Oh,” said mother, “telling fortunes.” Little Willy, for a lark, Put his father in the dark. Acid eye-drops for surprise— Blinded both his father's eyes. Said the Father, feeling stun-ished, "Little Willy should be punished." EXHORTATION All you people full of skillies, Do a bunch of Little Willys!