"The Emperor's Shoestrings" (1974/1997)

- Jon Nelson

- Dec 31, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 3

I refrain from writing "The End" here. It must not end. — "The Day After the World Ended"

“C’mon, Justin,” came an ankle-high voice from a small lady, with the red-thread or fairy mark on her throat and with a Jewel-Bird egg in her navel. “These illuminated people get mighty murderous if you don't use their brand of light. They'll kill you. Let's go to the thirteenth. C’mon.”

Today I want to look at Lafferty’s “The Emperor’s Shoestrings,” a fun story that doesn’t get much attention. I also want to use it to step back to a larger question that matters for reading Lafferty in general: the much-remarked, pervasive presence of death in his work—and the puzzle everyone eventually chews on. Why is death in Lafferty not the miserable thing it is in most other writers?

At the end of the post, I’ll include a first-pass resource on what I take to be a recurring pattern in his fiction: definalization. Definalization is bigger than death—death is just where it shows up most dramatically, since nothing is more experientially final than dying.

In most fiction, death enforces closure: a character exits narrative space, or returns only in restricted forms through memory. Definalization displaces that kind of closure. It breaks the “death = narrative punctuation” rule and reopens the board, giving the story new lines of action:

“A one-handed man named Buford Cracksworthy, in a moment of panic, had lopped off his own head. "Here, here, here," the chief of the WHEW crew cried. "That isn't allowed at all." "Oh boy oh boy oh boy!" the severed head moaned in severe unease.

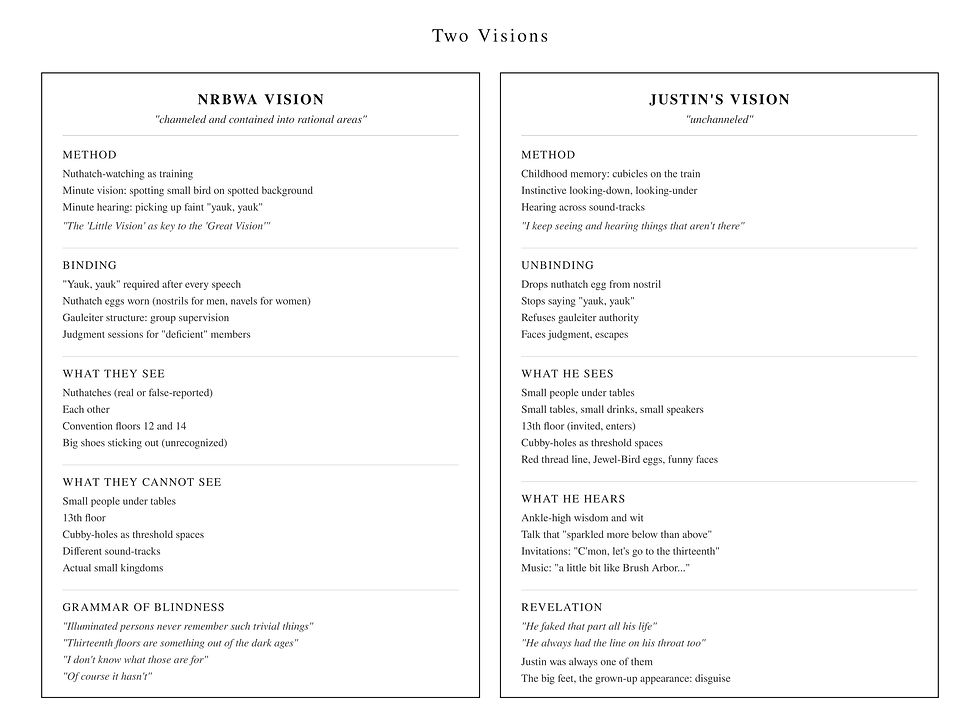

In "The Emperor's Shoestrings," Lafferty gives us Justin Saldeen. Justin is a birdwatcher attending a convention of the Nuthatches and Related Birds Watchers of America, or NRBWA. The NRBWA is as much a parafascist cult as it is a hobbyist organization. It is devoted to what it calls the “Little Vision” and enforced through constant loyalty tests. Members must punctuate every statement with the nuthatch’s cry, “yauk, yauk.” Everyone congratulates everyone else on their powers of perception.

Justin’s companions, Rolf Mesange, Berthold Chairmender, and others, are strict adherents of the yauk-yauk code. Justin, being a Lafferty hero, becomes distracted. He notices something his peers either cannot see or refuse to see: a gathering of small people beneath a table. Despite skepticism and hostility from the other birdwatchers, Justin is drawn toward the little folk. He makes contact with a woman who bears a thin red line around her throat. She invites him to join them on the hotel’s non-existent thirteenth floor.

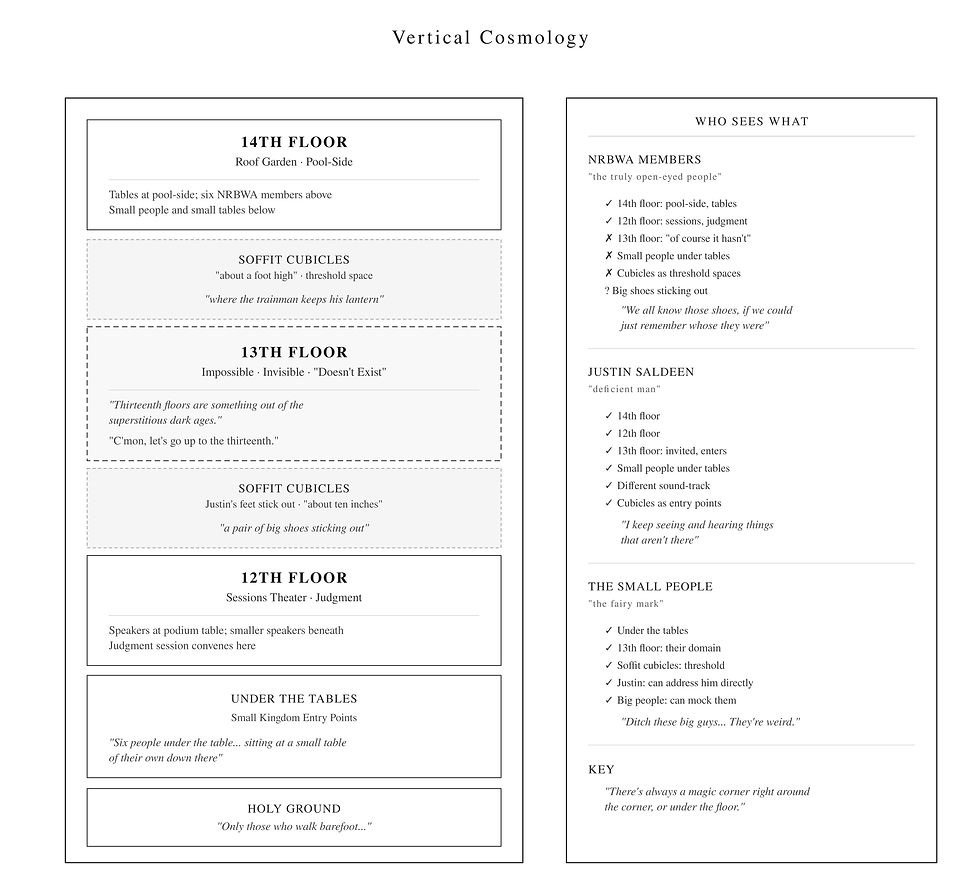

There is a great deal of vertical movement in the story, and for Lafferty, a mythographer if ever there was one, vertical movement is never incidental. It tells us about higher and lower things. Convention members shuttle between the fourteenth-floor roof garden and the twelfth-floor theater, missing what matters entirely, the small kingdom of the little folk. Justin, by contrast, becomes fascinated by the hotel’s in-between spaces, the small cubbyholes lodged between floors. They remind him of lantern compartments from a childhood train ride, little recesses you only notice if you are looking for what does not quite belong to the main architecture.

While the rest of the group attends lectures on “re-entrant space,” Justin disappears into one of these interstitial spaces, his feet left sticking out of the opening. This creates institutional pressure. Rolf will lose his NRBWA standing if he cannot account for Justin. Eventually, Rolf finds Justin’s shoes, and the group drags him back into conventional reality to face a scheduled judgment.

Enter the judge-advocate, humorless and dead to spirit. He accuses Justin of “deficiency” for his association with the small kingdom. Picking up an earlier conversation about Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” Justin offers a different reading of the tale. The child did not merely discover that the Emperor was naked. He discovered that the Emperor had willingly removed his shoes in order to walk barefoot on the holy ground of invisible kingdoms. This is the didactic core of the story.

The judge rejects the defense. All small kingdoms must be denuded; they must be visibly integrated into the larger order. The confrontation breaks out into chaos as the little people manifest openly, and Justin sides with their hidden reality. It is at this point that the group notices Justin himself bears the red mark around his throat. The discovery reveals that he is not just joining the murdered. He has been one of them all along.

“The Emperor’s Shoestrings” is, in many ways, a fairly straightforward Lafferty story. It affirms the invisible and sacramental dimensions of reality. It teaches lessons Lafferty teaches often, from “Boomer Flats” to “The Man Who Lost His Magic.” As usual, he sides with imagination and with life, a familiar affirmation. I want to set it aside here and attend instead to a concrete detail in the story, the red line around the throats of the little folk.

Death is puzzling in Lafferty. His fiction is a jolly abattoir, and at times death carries real weight—the kind we’re used to. But while there are brutal, stony deaths in Lafferty, more often death is less grim than it is in almost any other writer.

In other words, death doesn’t organize attention the way it does in most fictional patterns. In most stories, death draws things together: it pulls the narrative toward closure. It quilts the text down. It gives the reader the sense that what has happened adds up to a terminus. Death is summative, and theme is summative, so death becomes a high road to the interpretability of theme. It just doesn’t work that way in Lafferty. When we read him, we don’t worry about characters dying, because death doesn’t act as a thematic punctuation mark—at least not in the usual way.

In Lafferty, death is a heightened instance of something more general and more philosophical: the loosening of endings of every kind. He pushes the final moments—the death moments—into the center of attentional space, only to strip them of finality. And then he presses on, going where other writers stop. This is definalization where death becomes a blood-clotted knot of meaning that indexes his other strategies of definalization—enabling strategies, the ones that make his strange architectures possible. There is resurrection, the simplest way around death. There is ghostly persistence. There is the bending of time. Parts outlive the whole: a head is lobbed off and talks. Lost states return, often improbably.

In Lafferty, death intensifies something more general: again, the loosening of endings of every kind. He puts the moment of death at the center of attention, then strips it of finality and keeps going. That is definalization. Death becomes a blood-clotted knot of meaning because it concentrates the techniques by which his stories undo closure—resurrection, ghostly persistence, bent time, parts that outlive wholes, lost states that return, and so on. Simply put, death makes definalization visible.

In “The Emperor’s Shoestrings,” definalization takes the form of an image. It is the red thread, “the mark sometimes affected by those who have been murdered.” Lafferty repeatedly calls this throat mark on the little people a “thread,” and by the end of the story, it becomes a counterimage of the titular shoestrings. Where the shoestrings signify the bindings of the Big Vision, what the emperor tosses aside when he steps on holy ground, the red thread stands in for sensitivity to spiritual realities. It shows that the tie to the self-professedly rational world has been cut.

The little lady warns Justin that “these illuminated people get mighty murderous if you don’t use their brand of light. They’ll kill you.” That is about as Lafferty a sentence as one is likely to find. Within the birdwatching metaphors of the story, to bear the red line on the throat is therefore to be un-nested, released from the truly lethal rules of the Big Vision. It frees one to move through the crawlspaces, where the world opens into “murder comedies and haunt skits.”

There is a phrase in the story that beautifully captures this: “murdered but active.” Here, the blocking figure is the judge-advocate, the murderous enforcer who ensures that the scandal of something like definalization is not even recognized. He is a flat character, even by Lafferty’s standards—a mouthpiece for a settled world in which everything is accounted for. Yet when Lafferty lets the little folk parody him at the end of the story, the judge comes to life. He’s animated, as if by contact with something more living, a terrific image for what the story is out to accomplish:

The judge-advocate strode up and down the area inexasperation with his hands locked behind him. A muchsmaller man strode behind him, exactly taking off hismotions and attitudes. There were several of the othersmall persons japing about, but nobody looked at themmuch. And, really, they were not much to look at: they wereall quite small; they all had that thread-thin red line aroundtheir throats; and they all had funny faces.

The thin red line at the throat is a badge of definalization. It says that endings are meretricious—even if violence is not—and that the world keeps generating side-spaces and afterlives that no single, comprehensive vision can control.