"Symposium" (1965/1973)

- Jon Nelson

- Nov 24, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Nov 26, 2025

Philosophical, unloved Lafferty this time.

"Symposium" is not reader-friendly, so it is no surprise no one talks about it. As with the demanding "Buckets Full of Brains," Lafferty is more interested in his ideas than in charming the reader. Summary without commentary is also unhelpful in its case, so let’s cut to it.

Here is a metaphysical story about mechanical, chattering alphabet blocks in a child’s toy box. The blocks do not know the most important fact about their story-world, that they were designed, and that their teloi is to be toys. All in “Symposium” branches from this ignorance. If you don’t buy into the premise, this one is going to leave you cold. Lafferty also puts his thumb on the scale in a way that would look outrageous to a Lafferty reader like the philosopher-linguist Paul Saka. He stacks the deck, then lets the philosophical speculation of the chattering blocks begin.

One level deeper, however, is something else. Lafferty dramatizes Aquinas’s arguments for the existence of God in a playful way and creates comedy from it. The five ways would have been part of his Augustinian, private school education. One flaw in “Symposium” is that the five ways won’t be a fun reading experience for most readers. This just isn’t what people want from their cotton candy Okie. It is very Chestertonian in that Chesteron is usually more fun than his fiction, and his fiction is fun because it is Chesterton.

Let’s begin with the cosmological argument from Aquinas’s quinque viae, which the alphabet blocks debate from the perspective of created beings. The story itself functions as an ironic, indirect proof that a Creator exists, because the reader knows what the characters do not: they are toys, and they were made. We are not like men and women weighing Aquinas’s arguments from natural reason while reading the Summa Theologica or like undergrads reading an extract from it in an introduction to philosophy course. We are more like angelic intelligences who already know Aquinas is right because of how Lafferty has constructed the story world. We see more the blocks see. We can see teloi. They are toys.

Here is how the story works, beginning with the argument from contingency.

The cosmos is contingent. It did not have to exist, and it cannot create itself. There must be a Necessary Being (God) who caused it to be. “Symposium” begins with the Primordial Tumble (the Big Bang/Creation Point), whatever we want to call it. The blocks describe being disgorged from a World-Box. The blocks know that they did not create themselves. They know that they were dumped into existence by an external force. They can, as it were, perceive the cosmic red shift. This is the little girl playing with her toys, dumping them into the place space. In Catholic theology, it is creation ex nihilo, with the World-Box being the mysterious source of all matter. At that seems to be the correlate. The box was contingent and it contains the blocks. Heidegger would not like this. It is sheer ontotheology.

From there, we move on to the argument from motion, also known as the argument from the First Mover, which goes back to Aristotle. The idea is that nothing moves unless acted upon by another. There cannot be an infinite chain of movers, so there must be a first mover who started the process. Kant would later say that is antinomy territory, the place where the pure categories spin on themselves because they are dealing with the unconditioned, and any object of experiential knowledge must be experienced through both the senses and the concepts of understanding. The non-Kantian might think everything needs a cause but the first cause has no cause, and experience aporia. It is as if we are trying to see the back of our head. When pure concepts do not have experience to process, they are like the jogger who has had his shoelaces tied to each other. For Kant, this would be pure categories of understanding treating themselves as of they were objects of experience. Lafferty would have none of that. He is no Kantian but a philosophical realist.

We see this become an issue with Gee (G) and Zed (Z). They discuss the ontothological frame. They are aware that their motion and existence are limited to a specific area (space/time). In other words, the blocks cannot move themselves. They are wood or whatever. There must be arche of motion. When the blocks move, it is because the Child, here playing the role of the Prime Mover, moved them, or because they are engineered. Their debate about motion just is the Aristotelian/Thomistic view that the universe requires the primary push from God that supports secondary motion.

From there we move on to the teleological argument, known as the argument from design. This argument has some popular recognition because of how often it shows up in the embarrassing intelligent design arguments of well-meaning Protestants and because of how hard the New Atheists went after them over a decade ago. When I used to teach historical geology, I would occasionally get push back about deep time from fundamentalists and the necessity of design. In any case, the argument is that the complexity of the universe implies a designer, from trilobites to nephrons in one’s kidney. The best-known form of this is the 18th-century watchmaker analogy of the Anglican William Paley (1743-1805). A complex mechanism cannot arise from random chance. If you found an iPhone on the beach, you would know it was designed and someone and had been either lost or abandoned

A conflict next arises between En (N) and Ex (X) over the electric motor. En is our theist. En argues that a "four-pole electric motor" is too complex to appear in a swamp by accident. It cannot exist without a designer. Ex is our materialist, our atheist, a figure that runs from the Epicurean philosopher Lucretius to the microbiologist Richard Dawkins. Ex says that given enough time ("all the time in the world"), natural copper and iron just happened to fall into the shape of a motor. Lafferty here mocks abiogenesis and materialist evolution. If the reader has not fallen asleep, the reader knows En is right. Ex and En are toy blocks; the motor inside them was designed by a toymaker. Lafferty’s gambit is simple: show how ridiculous Ex sounds ("two rocks rubbing together") and validate the teleological argument: intricate systems (life/cosmos) index a creator. There is also a rather obvious pun on being outside truth (Ex) and inside it (En).

Then there is the argument from degree, sometimes called the argument from perfection and hierarchy. The idea is that we notice gradients in things (hotter, better, larger). This implies a maximum standard (God), the principle of perfection. It is how we get the Great Chain of Being, which is in all Lafferty and a key to understanding Past Master (1968). This phase of the dialogue is filled with Ar (R) and Thorn (Þ). They discuss size, scale, and hierarchy. They debate if atoms are solar systems and if the universe is infinite or cyclical, Augustine or Origen. This is all a little funny because the characters are confused about their place in the hierarchy. They think they are the masters of the universe ("adult and intelligent"), but the reader knows they are at the bottom of the play hierarchy (toys). This reflects the Catholic view of humility: man is not the measure of all things; God is. Of course, Thorn is the Anglo-Saxon letter that represented a diphthong, which is why Ye Olde Shoppe should be pronounced “The Old Shop,” even if one can forgive the coyness of “shoppe.”

Finally, we arrive at the concept of actus purus, the vivifying principle. As I have blogged about probably too much, for Lafferty, God is Pure Act. Matter is Potency. Matter cannot exist without the sustaining will of God (the soul/life). Lafferty is a Thomist on these points, and without such knowledge, a story like “Symposium” will not make sense and one will not be in a position to understand how he treats characters such as Ouden.

How does this show up in the story? You (U) argues about the vivifying principle. He says that "life and matter may have been simultaneous." The vivifying principle in the story is literally the electricity/battery in the toy. Without the juice (spirit/God's grace), the block is just dead wood or metal (dead matter). It is also a metaphor for the Holy Spirit animating the clay of Adam.

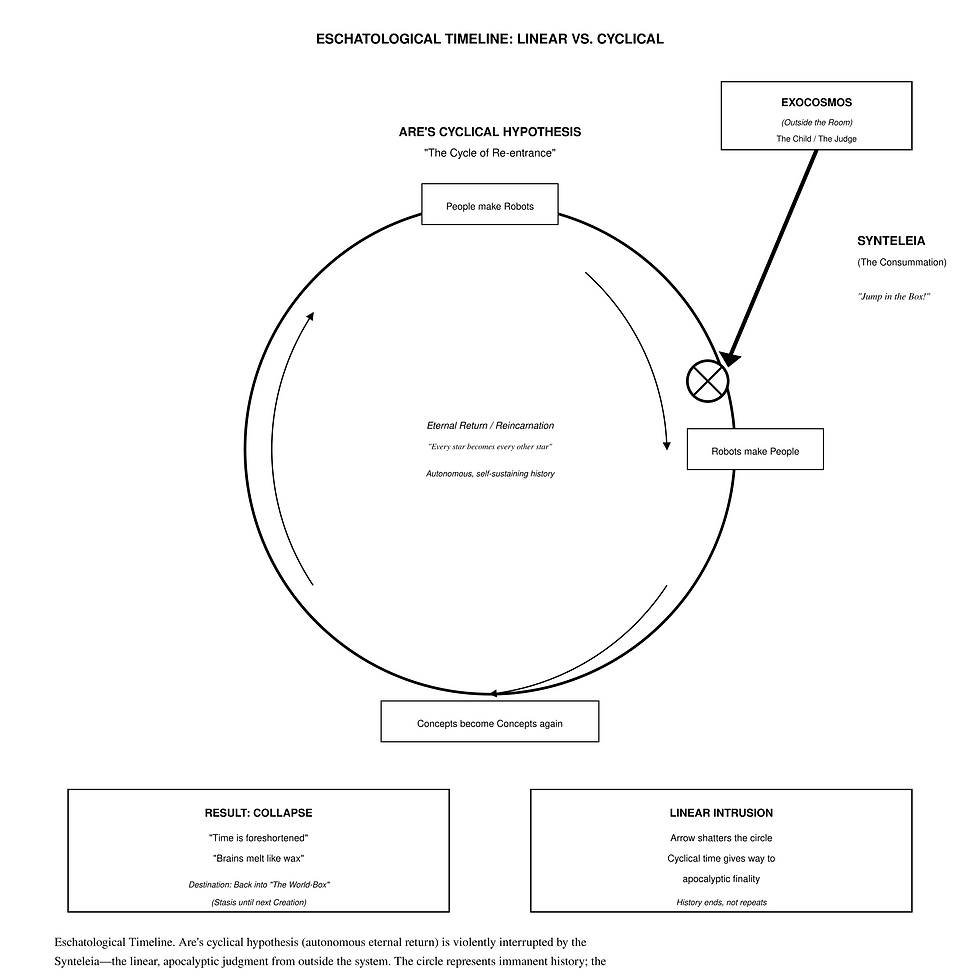

The synteleia is one of the more Christian elements in the story because it comes not from natural reason but from revelation. Catholicism is always focused on eschatology: the four final things. The universe is linear in one sense, not circular. It has a beginning (Alpha) and an end (Omega). Synteleia is the Greek term used several times in the Gospel of Matthew for the consummation of the age or the end of the world.

And as he sat upon the mount of Olives, the disciples came unto him privately, saying, Tell us, when shall these things be? and what shall be the sign of thy coming, and of the end of the world? (Matthew 24:3)

Pea (P) announces the synteleia: "The kid with the box.” This is a little confusing, but not overly so. For the Lafferty, the end of the world is not a random heat death; it is a person returning (Christ). In “Symposium,” the God figure (the Child) returns to judge the living and the dead (the blocks) and put them back in the box (Heaven/Hell/Purgatory).

And that leaves us with the scandal of tradition: Thorn. The deposit of faith. Needless to say, Roman Catholics are quick to point out that Catholicism is a historical faith rooted in tradition. Modernity often tries to smooth over the awkward or "shaggy" parts of the past, parts like Thorn—the miracles, ancient dogmas—to make faith fit modern science. But Lafferty is saying that Thorn (Þ) isn’t going anywhere. It’s the old letter that doesn't fit the modern box. Thorn remembers the shaggy old days of giants and miracles. If there is a character in the toy box that is Lafferty, it is Thorn, the traditionalist Catholic view. He won’t be modernized or smoothed down. He is the “stumbling block" (a biblical metaphor). The modern world rejects Thorn because he doesn't fit the current pattern, but he remembers the ancient truths. The other letters are amnesiac about our old pal Thorn.

This will not be a Lafferty story that many people think about much, but it is one of his quirkier theological games.