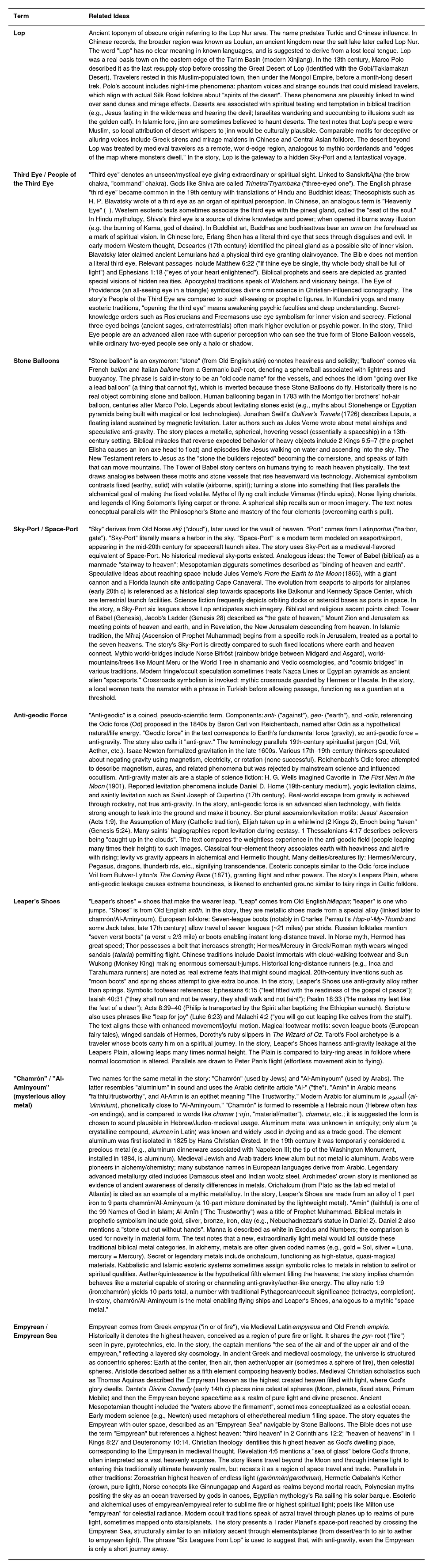

"Six Leagues from Lop" (1980/1988)

- Jon Nelson

- Nov 27, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Nov 28, 2025

“You will hear it for yourselves, and it will surely fill you with wonder.” — Marco Polo, The Travels

“All the voyages, whether to the moon or to worlds ten million times more distant, take about the same time to complete," the sea captain said. "When you use anti-geodetic force for propulsion, all places are equally close, all places are really only “six leagues from Lop. Come. It is a great enjoyment if you have not traveled to far places before!"

What an unusual story “Six Leagues from Lop” is. It may be Lafferty’s most extended act of ventriloquizing a historical voice, with much of it written in the mode of a found manuscript by a real figure. It is also remarkable for the way it uses that pseudo-documentary frame to mask what is, in fact, a transparent allegory—or, more precisely, a directly allegorical anagoge. That last point is what makes it so fascinating. It doesn’t feel like didactic Lafferty, yet he is rarely more medieval in his didacticism.

The found-text device interests me. By training, I am an eighteenth-centuryist, and one of the principal ways the modern category of fiction emerged was through the early novel’s pretense to documentary. Lafferty, by contrast, is trying to move beyond the model of fiction that places the novel at its center. This technique, whether called found fiction, pseudo-documentary, or something else, was the beating heart of early English fiction. Many of its writers used such forms to lend their narratives an air of authenticity at a time when long-form prose fiction had not achieved any cultural legitimacy. The most famous examples in the English canon are Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Gulliver’s Travels (1726). Both are packaged by their authors as genuine travel accounts, with the boundary between fact and invention destabilized. Swift, though, satirizes the device and takes pleasure in its exploitation.

In this pre-novelistic fiction—on the way to Richardson and Fielding but not yet the novel—one often finds edited journals, eyewitness testimonies, and discovered documents. Such forms draw on the authority of nonfiction genres, including voyage literature, spiritual autobiography, and political satire, leveraging their credibility to make the extraordinary seem either plausible or interesting. The earliest novels would follow suit, often adopting the epistolary form.

Lafferty does the opposite. He snaps it. He slams down spaceports into The Travels of Marco Polo (c. 1300), knowing exactly how alienating that suspension-of-belief shock tactic will be. I think he does it to dramatize the difference between a worldly vision and a sacramental one—and to poke fun at an imagination that balks at spaceports in Marco Polo but not other marvels. As if to say: yes, we all know there are epistemic problems in the Travels, stretchers, but you’re taking this anachronism business a bit too far with that spaceport thing.

In "Six Leagues from Lop," Lafferty creates a modern narrator. After a search, he recovers lost writing dictated by Marco Polo (1254–1324). The story then leaps to the future again, and what occurs in the dictated material begins to shape the narrator's modern experience, who is awoken to the marvelous—one text shaping the other, both pointing outward to Prime. Behind it is the historical problem that surrounds Polo himself, which Lafferty clearly enjoys.

You probably know the outline of this: Polo was a Venetian merchant and explorer who, along with his father and uncle, made a decades-long journey through Asia. The Travels records his time at the court of Kublai Khan, though the account has long been the subject of scholarly debate, with true believers and whistleblowers. What is incontrovertible is that Polo became known to Europe largely by accident. The book for which he is famous was not written by him, but was assembled from what he narrated while imprisoned in Genoa. His cellie and collaborator was Rustichello of Pisa, a far less recognized name.

And Rustichello is a problem of sorts, though he makes Lafferty's story possible. He was not merely a chronicler, but also a writer of romance; his Roman de Roi Artus, the first Arthurian romance in Italian, still survives. It is clear that his role was not that of a scribe keeping to the facts, but that of a shaping hand. He transformed Polo’s oral recollections into something closer to an adventure narrative, turning the life of a merchant into the arc of a romance.

.

The manuscript tradition that descends from this weird collaboration is immensely complex. The work was copied and translated into multiple languages almost immediately, including Franco-Italian, Old French, Tuscan, Latin, and later others. Each version introduced its own omissions, embellishments, and scribal errors. As a result, no single authoritative text exists. Look closely at The Travels, and you find branching versions with no clear path back to the trunk.

But for Europe, Polo’s travels became an ur-text. It was the foundational narrative that Orientalized the East and left a lasting imprint on the Western imagination. Polo’s East is full of marvels: cities glittering with wealth in Cathay (China), vast armies and paper currency under the Great Khan, the magnificence of Cambaluc (Beijing), giant ships with multiple masts and superior engineering that Polo is said to have tried to teach the celebrated shipwrights of Venice, miraculous stones that burned like fuel (coal), strange animals such as “unicorns” (rhinoceroses), islands ruled by powerful queens, and regions where people mined salt, pearls, and gold in astonishing quantities. In short, it is a catalogue of wonders that helped shape the medieval imagination and transform Europe’s understanding of the wider world.

Along the way, Polo mentions a nothing place. It is Lop, a historical location that one passed through before undertaking the arduous journey across the Gobi.

Since Lafferty builds his story on this reference, it may be worth quoting at length. The following is from Chapter XXXIX, mentioned by Lafferty:

Lop is a large town at the edge of the Desert, which is called the Desert of Lop, and is situated between east and north-east. It belongs to the Great Kaan, and the people worship Mahommet. Now, such persons as propose to cross the Desert take a week’s rest in this town to refresh themselves and their cattle; and then they make ready for the journey, taking with them a month’s supply for man and beast. On quitting this city they enter the Desert. The length of this Desert is so great that ’tis said it would take a year and more to ride from one end of it to the other. And here, where its breadth is least, it takes a month to cross it. ’Tis all composed of hills and valleys of sand, and not a thing to eat is to be found on it. But after riding for a day and a night you find fresh water, enough mayhap for some 50 or 100 persons with their beasts, but not for more. And all across the Desert you will find water in like manner, that is to say, in some 28 places altogether you will find good water, but in no great quantity; and in four places also you find brackish water. Beasts there are none; for there is nought for them to eat. But there is a marvellous thing related of this Desert, which is that when travellers are on the move by night, and one of them chances to lag behind or to fall asleep or the like, when he tries to gain his company again he will hear spirits talking, and will suppose them to be his comrades. Sometimes the spirits will call him by name; and thus shall a traveller ofttimes be led astray so that he never finds his party. And in this way many have perished. Sometimes the stray travellers will hear as it were the tramp and hum of a great cavalcade of people away from the real line of road, and taking this to be their own company they will follow the sound; and when day breaks they find that a cheat has been put on them and that they are in an ill plight. Even in the day-time one hears those spirits talking. And sometimes you shall hear the sound of a variety of musical instruments, and still more commonly the sound of drums. Hence in making this journey ’tis customary for travellers to keep close together. All the animals too have bells at their necks, so that they cannot easily get astray. And at sleeping-time a signal is put up to show the direction of the next march.

This is the passage around which Lafferty builds his story, and if there were ever a collected edition of his work with notes, this would be the place to include one. The contrast between the vastness of the Gobi on one side of Lop and Lafferty’s idea that everything is six leagues from Lop lies at the center of the story.

Our unnamed first-person narrator, relatively rare in Lafferty, tells us that The Travels of Marco Polo contains conspicuous sutures where material was removed. This leads to textual speculation. The narrator asks the question that will obsess him: "But Marco was a natural storyteller. Why are three or four of his stories pointless and too short?" Perhaps Polo’s cellmate, Rusticiano, found Marco’s most fantastic stories unbelievable—mere tall tales. What might he have done? Knowing they would command no credence, he may have stolen them, publishing them under a pseudonym of his own invention: Emilone Rusticanus, or “Big Emil the Rustic, ”a name that fuses both men, and both puns on Marco Polo's nickname ("Milione") and the Latin Aemilius, which means to rival, imitate, or aim to excel.

After a thirty-year search, the narrator is vindicated. He discovers one of the missing episodes, The Romance of the Stone Balloons, in a castle in Albania. He rents an Albanian typewriter and transcribes the manuscript in under an hour. The recovered episode turns out to be stranger than anything in the known versions of the Travels: a secret encounter Polo had near the desert town of Lop in the year 1275.

Polo claims that he met Sea Captains near the Gobi Desert who sail the sea of the upper air. One of these captains invites Polo to a nearby Sky-Port where he gives him what are called leapers shoes. These metal shoes are made of an alloy called "Al-Aminyoum" by the Arabs, and they react with the “anti-geodic force" leaking from the ships. This makes it so the wearer can stride "twenty times [their] own length." Polo learns that the floating vessels, known as "Stone Balloons," are really made of sophisticated metals, but to those lacking the Third Eye, they appear only as shadows or stone spheres.

Then the captain takes Polo on a voyage to a Trader Planet, perhaps one of the three we know from Lafferty’s other novels. The captain says that with anti-geodic propulsion, distance is irrelevant and all places are really only six leagues from Lop. He rattles off a list of local ports with the casual air of a bus driver: 'Two on the moon, one each on Mercury and Venus (stifling places those!), others on the moons of Saturn and Jupiter. On the Trader Planet, Polo describes giant merchandise fairs where wealth is so abundant that machines sweep the floors clean of dropped money which is then piled up like mountains for the poor. Polo trades his earthly linens—thought to be quaint things by the aliens—for dromedary loads of diamonds and gold. He goes back to Earth the next morning, hiding his inexplicable wealth from his family.

Lafferty’s story then jumps seven hundred years into the future. Our manuscript-hunting narrator travels to the modern Chinese oasis of Lo-Pu Po, current-day Lop, to verify Polo’s story. In a dark corner of a shop, he finds a pair of metallic leaper shoes. They’re covered in cobwebs, unvalued and not known for what they really are. A cynical woman tells him that he is being had and buying magic beans: the shoes are "genuine imitation modern American cowboy boots" made to fleece tourists like the narrator. Ignoring the warning, the narrator buys them for twenty dollars American. He rebuts her skepticism with confidence, saying, "I am satisfied" and "The metal shoes are telling me where to go." And the shoes work. He goes "striding along with longer and longer strides," guided by the mechanics of the boots toward the ancient, hidden Sky-Port written about in the manuscript.

At the port, the narrator meets the three-eyed beings who speak a lingo resembling Turkish. Being dead broke after the shoe purchase, he has nothing to trade but an old pocket knife with a broken blade and a synthetic handle. To his surprise, the aliens are curious about Ersatz-Earthian artifacts, even saying that "the more broken they are the better they like them." So he trades the knife for a fortune and becomes independently wealthy for life. A bit like Lafferty’s Roadstorm in Space Chantey (1968), boredom eventually sets in, and the narrator tells us he is resolved to find the remaining lost Polo adventures, specifically the Fountain of Youth.

This is a story where the sacramental angle is easy to miss. The pseudo-documentary frame is skillfully handled, and the spaceport motif and stone balloons are so thoroughly defamiliarizing that they draw the reader’s attention elsewhere. At least, I have seen no one point out how overtly medieval and allegorical the structure really is. So I’ll spend the rest of this post focusing on just that, because what we have here is a spiritual pilgrimage embedded in a science fiction tall tale that pretends to be found fiction.

There is a technical term for this, which I used earlier, anagoge. Most of the time in Lafferty, the anagogical erupts through other narrative frames. In this case, however, he offers a relatively straightforward anagoge, the kind he rarely uses, but he conceals it. It is a clever move.

More precisely, anagoge refers to the mystical ascent of the soul toward higher, divine truth. You find it throughout Neoplatonic writings—Plotinus’ account of the soul’s ascent is a classic example—as well as in early Christian allegory and medieval exegetical theory. It is the sense behind the sense. And it is why this blog never tires of insisting that Lafferty must be read anagogically: as a writer whose texts point upward and, through implication, downward.

For reference, the tropes Lafferty plays with in this story are ones any educated humanist would recognize. The most obvious is the Somnium Scipionis (through Macrobius), which, along with Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, was once standard reading for educated Catholics. In the New Testament itself, the tradition appears most clearly in St. Paul’s vision in 2 Corinthians 12:2–4:

“I knew a man in Christ above fourteen years ago, (whether in the body, I cannot tell; or whether out of the body, I cannot tell: God knoweth;) such an one caught up to the third heaven. And I knew such a man, (whether in the body, or out of the body, I cannot tell: God knoweth). How that he was caught up into paradise, and heard unspeakable words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter.”

These are anti-geodic moments. That is why Lafferty uses the word geodic and not gravity. It is the verticality of anagoge that matters. Gravity is not inherently vertical; it acts as a radial pull toward a mass. But one ascends “up” toward the empyrean and descends “down” toward Earth. These human-to-God and God-to-human orientations arise from our embodied position within a gravitational field—if gravity is to be invoked at all.

If you asked someone to translate anti-geodic after reading the story, and that person answered anti-grav boots, Lafferty would have exposed the person as the kind of reader who, like the woman in the story, sees cheap merchandise in the leapers shoes (the merchant has "whistled for his pet spider to come and spin more webs over them"): a science-fiction trope with some indifferent technobabble for flavor.

Again, what matters is the vertical ascent. Given Lafferty’s knowledge of Dante, it is hard to believe that this is not somewhere in his mind. In Paradiso, the pilgrim journeys through the heavens to the empyrean and beyond. Along the way, he passes through the upper air, the realm of lightning, before entering the sphere of the moon. All of these belong to the conceptual background of Lafferty’s story.

Here is Dante on the pilgrim’s ascent, from Paradiso I, as he and Beatrice cross the boundary of the Elemental World into the celestial spheres:

“I saw myself raised upward, borne aloft by the pure brilliance of the inner light; and so I rose into the higher fire.”

Here is Lafferty’s Marco Polo from the narrative within the narrative:

“One of the sea captains explained to me that he was indeed such, but that the sea he sailed was the sea of the air and of the upper air and of the empyrean which is still higher than the upper air.”

The idea of the upper air here is drawing directly on Aristotle and medieval science:

“Fire occupies the highest place among them all, earth the lowest, and the other elements correspond to these, air being nearest to fire, water to earth.”— Aristotle, Meteorologica, Book I, Chapter 2 (339a15–19)

‘. . . that fire is always light and moves upward, while earth and all earthy things move downwards or towards the centre.”— Aristotle, On the Heavens (De Caelo), Book IV, IV.4

Because I suspect the story is often read as a simple wonder tale and then forgotten, I will spend the rest of this post drawing out its didactic dimension.

We are given Marco Polo’s found-text, followed by the modern narrator’s act of verification. This structure mirrors the Christian soul’s ascent toward the divine in most anagogical narratives: a movement that follows truth. It is also the meaning behind the line, “all places are really only six leagues from Lop.” But why are all places only six leagues from Lop? As I have said elsewhere, a reader of Lafferty ought to have some answer to that kind question, especially when Lafferty makes it so plainly worth asking.

Given other elements in the story, it reads to me as an allegory of the nearness of grace: the distance between the mundane and the transcendent is short, bridged instantly by the presence of God. Geographical space is compressed into spiritual immediacy. God is never a Gobi away. Salvation is not the result of long effort on the part of the traveler—like the historical Marco Polo preparing to cross the Gobi, over five hundred miles of desert, beyond Lop—but the fruit of sudden, divinely oriented recognition.

Here are just some of the more obviously allegorical elements. Marco and the narrator acquire great wealth with almost no labor—a parallel to the Gospel’s freely given gifts and the Parable of the Talents. As the narrator puts it, 'I didn't understand much of the trading, but there seemed to be no way that anybody could lose." The Trader Planet, where treasure is endlessly replenished and swept up by the poor. It figures the inexhaustible mercy of God in the New Testament, the sacramental meaning of daily bread.

Lafferty’s most overt anagogical symbol is the leapers shoes and the anti-geodic easing of burden: being lifted, not dragged, through anagoge. As Polo describes the sensation, "My riding donkey went high into the air at every stride . . . It is very pleasurable to stride along a ground that is saturated with anti-geodic force." There are also the revivifying pellets, and the Stone Ballons—another of Lafferty’s emblems of the Faith. Like the barque of Peter, or another iteration of the Argo, they are heavy-looking but light; shadowed from without, bright within.

There are many small, comic touches in this story, like the joke about aluminium with the pun on "Al-Amin," Arabic for the trustworthy one. No matter how brilliant Da Vinci may have been, he wasn’t going to fly without aluminum. It is a textbook example of advances in material science making room for secular marvels.

On the allegorical side, the rest should fall into place, including the People of the Third Eye, an image of perfected faith and vision.

I’ll close by noting that the narrator’s promised search for Marco Polo's Fountain of Youth manuscript shifts the story’s focus from plena gratia to eschatological hope. This is Lafferty in a good mood, worlds apart from the eschatological pessimism of “And Name My Name.”

“Are those great spheres that I see the vessels that are called the stone balloons?” I asked the sea captain. “Yes, they are called the stone balloons,” the sea captain said. “It is an old code name. They are really made of the most sophisticated of metals. And you do not see them, since you do not have the third eye. You see only the shadows and auras of them. But with practice that is nearly as good.”