"No Valid Characters in SF"

- Jon Nelson

- Jan 20

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 20

Lafferty’s ontological distinction between characters and persons is underappreciated in part because modern ideas of personhood have been shaped by mass-mediated character and by the categories of modern psychology. The modern person thinks nothing of bumping into the Narcissist or the Borderline, but would be taken aback by bumping into Vice. Daniel Otto Jack Petersen has pointed out that an interesting parallel to Lafferty’s work is the medieval dream vision. This strikes me as absolutely correct. I have written a few times recently about how important it is to remember that Lafferty does not write characters in the modern sense, so I want to share an important Lafferty fragment on the topic and say something about it here, though much of it will likely seem obvious. This is not to teach anyone how to suck eggs, but because I want the point worked out clearly for the blog.

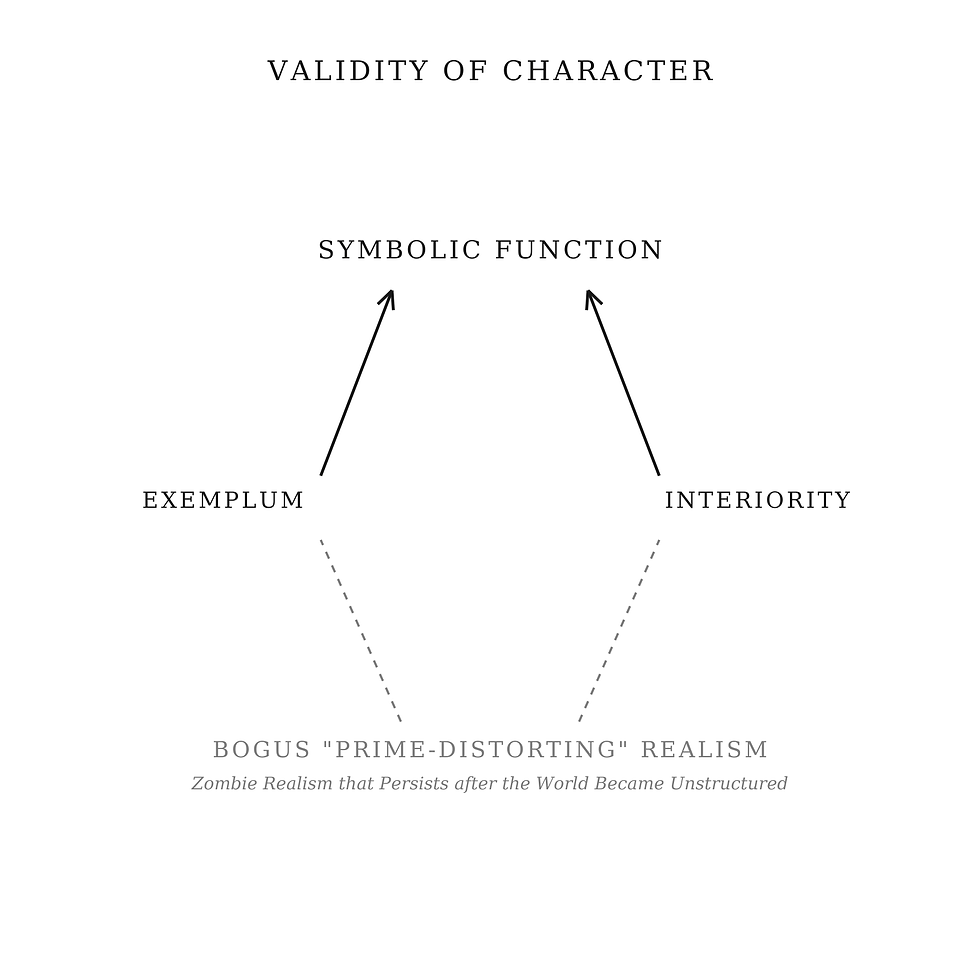

I think one is far better served reading Lafferty’s characters as a post-novelistic return to older ways of handling character than as what science fiction usually does: fake at realism to buy legitimacy for a novum. This is an important area in which Lafferty is decidedly not of the New Wave. My understanding is that he did not like this bogus realism (actually romance) element because it smuggled in ideological positions that he believed were distorting of the higher realism, the one that in his work stays true to Prime, even if what results looks nothing like literary realism. For lack of better language, Lafferty readers have been stuck calling this the tall tale because Lafferty's oceanic inner space is not Ballardian inner space, because Lafferty turns people inside out to create worlds. He does not create worlds to explore people or understand how technology shapes psychology, at least not most of the time. There are exceptions here.

A few fairly basic points. Medieval characters feel unlike modern realist characters because medieval literature was not trying to imitate everyday psychological experience. Its primary purposes were moral, religious, and social instruction. Lafferty gets his extreme didacticism from this tradition, whose characters are, more often than not, exempla—virtues, vices, or social roles. They are not individuals with changing inner lives. The academic tendency is to qualify everything to avoid being accused of being reductive, but in this case, reduction fits the facts.

Medieval thought tended to treat identity as stable and externally defined, outside of highly patterned forms such as conversion narratives: who you are is determined by your role and by your relationship to God and society, not by inner conflict or self-discovery. What inner conflict exists is not oriented toward self-actualization in the modern sense, but toward actus in the Aristotelian sense. Psychological ambiguity weakens the clarity such texts aim to provide, especially in cultures formed by allegory, oral performance, and communal interpretation. Just ask a medievalist about silly things said about medieval characters. This is, of course, what medievalists now call medievalism—the Orientalist-style projection of fantasy onto a source. All the heroes pursuing the Dark Lord after collecting the plot coupons are thinly veiled Americans.

What Lafferty shows is what happens to the exempla readers have been taught to call “flat” (an aesthetic ideology) when two things change: first, they are placed against contemporary-looking furniture; second, the conditions of world stability that made medieval exempla possible have disappeared, even as the truth-function of those conditions persists. Here, a qualification needs to be made, because Lafferty’s characters are not medieval exempla. They are that literary technology after it has passed through highly conventionalized marketing genres, though some of Lafferty’s best short stories are outside-genre and pull closer to exempla simpliciter.

So Lafferty’s published characters are strange, with Dotty in the early novel Dotty being a major exception. Dotty was a prenucleation creation. As he writes, Lafferty's characters more clearly exist after the historical changes that made interiority narratively meaningful have become a problem for him. Those changes include the rise of philosophical nominalism in the late Middle Ages, Renaissance humanism, print culture, increased social mobility, and transformations in how society reproduces itself. What followed was a dialectic. Identity begins to look unstable and self-defined, and literary representation explores motivation, contradiction, and development over time.

Where the traditional modern approach treats character instability as the result of relatively recent historical contingency, Lafferty does something inventive. He treats instability as the result of the Fall, which is far more medieval than modern. He explores it as a counter-image to the inner divisions mapped by the cartographers of psychological realism. At the same time, he intensifies character type, something he partially conceals through his genius for naming. He is so good with names that he makes types look like extreme particulars through the sheer brilliance of his understanding of language.

My take is that Lafferty does this because he knows that type characters are not primitive or poorly written; they are complex in a different way. We see him thinking through this in "No Valid Characters in SF." They exist within a Weltanschauung that prioritizes moral legibility and symbolic function over inner psychological richness. Lafferty created a macro-environment (the Ghost Story) for his own creations to explore what happens when the Catholic horizon overlaps with late modernity. He knew that medieval characters answer different questions—about virtue, duty, and order—than modern characters, who are built to explore interior life and personal change. Those are the questions Lafferty was intensely interested in while being intensely interested in technology. If this seems overgeneralized, one ought to note Lafferty’s own categorical negation of valid characters in sf.