"Milly" (1957)

- Jon Nelson

- Oct 5, 2025

- 5 min read

The objective truth as such is by no means adequate to determine that whoever utters it is sane; on the contrary, it may even betray the fact that he is mad, although what he says may be entirely true, and especially objectively true. I shall here permit myself to tell a story, which without any sort of adaptation on my part comes direct from an asylum. — Søren Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1846)

Like a handful of other Lafferty stories, "Milly" is not included in the most recent The Man Who Told Tales. That is a shame. It is a very fun story. Over ten years ago, Andrew Ferguson wrote about it and pointed out the alliterative names. He also noted that Virginia Kidd once remarked on this habit in Lafferty’s work. After that, Lafferty seems to have toned it down. I am thankful for Kidd’s comment. It probably pushed Lafferty to become even more creative with the names he gave his characters. As we all know, his character naming best tools we have for understanding his work.

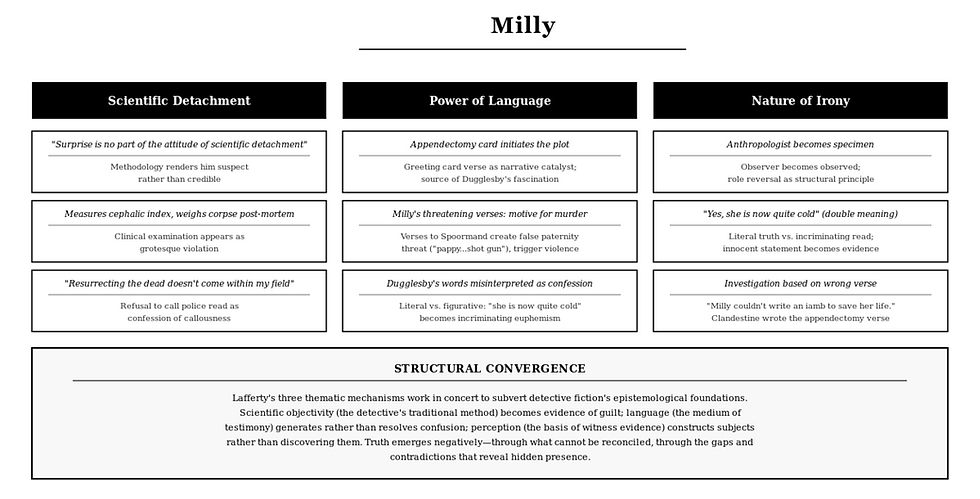

So what is "Milly"? It is a murder mystery, but that does not quite capture what it is. It is more accurate to say that it uses the murder mystery format to explore themes of perception, causality, and the friction between logical systems and human experience. In this way, it is very much a Lafferty story, and it has excellent dialogue. It's a satire of the "whodunit." It all begins with a strange greeting card verse about a "happy appendectomy." From there, Lafferty puts a deeply detached anthropologist at the center of the crime, armed with essentials like Guelf’s Cephalic Tables and Sweet’s Slang Dictionary. This anthropologist is not interested in murder, but in the kind of young woman who writes greeting cards and thinks like his ancient and capricious Aunt Agatha Asquith. From this starting point, the typical, lurid, and trashy parts of a normal mystery story get short-circuited because "Milly" is a mystery story that refuses to get in line.

Take an uninspired interrogation scene from an average piece of Alfred Hitchcock Presents or Ellery Queen. The detective asks smart questions. The suspect gives slippery answers. Clues fall into place. In "Milly," it does not work that way. The following interrogation shows what kind of game Lafferty is playing.

“Did you kill the girl?” “Of course I didn’t. I never kill people.” “Do you know who did?” “I believe so. Since she could hardly have done it herself, I believe it must have been a third person.” “Would it be asking too much if you know the name of the third person?” “No. I have no way of knowing that.” “She was dead when you arrived?” “Yes. Recently but conclusively so.” “Then why didn’t you do something about it?” “I am a scientist — in my opinion, a very clever one. But resurrecting the dead doesn’t come within my field. When it is infrequently done, it is more likely to be done by a religious or a mystic than by a scientist of any sort. I didn’t do anything about it because there was nothing I could do about it.”

The story’s driving force is the man being questioned, the anthropologist Dugglesby Dunham, whose déformation professionnelle blinds him to normal social and ethical standards. When he finds Milly’s body, he shows no horror and no sense of civic responsibility. He follows only the methods of his research. He treats her body as a set of data, using calipers to measure her head and recording a "cephalic index of seventy-eight." He notes with clinical frustration that "there is something very contrary about a dead girl when you try to stand her up and measure her." His detachment reaches a high point during the police interrogation and starts to weaken slightly afterwards. His opponent is not just any officer, but a crude lieutenant named Eric Spoormand (the real killer), who eats peanuts while questioning him. Dugglesby justifies his behavior (research) with an analogy: "How often will a policeman phone an anthropologist when he sees an interesting type in the course of his day's work? You would be surprised how seldom." Dugglesby is one of Lafferty’s caricatures of the person who sees the world only as a collection of facts.. The binding normative force that guides most people does not move Dugglesby Dunham.

Pretty early on, it becomes clear that the story will focus on flawed perception, with a group of characters who have names like Clandestine Carney and Shoo-Shoo Schoengeist. A typical mystery moves forward by uncovering facts. This story moves forward by building up mistakes. The “handle” needed to solve the case is eventually pieced together from three conflicting descriptions of Dugglesby: to Clandestine, he is a "sweet little red-headed man"; to Shoo-Shoo, a "crude little greaser"; and to the greeting card printer, an "old Phoenician," he is a "big buff man, sort of a cowboy type." Even Dugglesby, the trained observer, joins in this confusion. He misreads the girls’ screams of terror as a cultural ritual and writes in his report that women of their "vagrant type" "greet each other with loud screaming." In this early and light story, there is already a trace of Lafferty’s interest in consensus reality, where what people accept as real is often made up of shared misunderstandings. Solutions come from both secrets and anti-secrets, from seeing the mixed-up and hidden patterns inside these collective mistakes.

When thinking about this story, I realized that something at work in much of Lafferty’s writing is what we might call the principle of disproportionate causality, where huge and deadly results come from small and unimportant causes. He enjoys this kind of setup, and it shows up here. The motive for the murder comes down to the greeting card verses written by the victim. Milly turns out to be not only a murder victim but also someone who might have been pregnant. One of the verses she sends him is:

I’m sure we’ll be happy, And don’t say it’s not done, ’Cause I’ve got a pappy, And he’s got a shotgun.

Spoormand, who wanted to marry someone with money, found the greeting card verses unbearably irritating (“there ought to be a law against writing verses like that with a needle in them”). One of the better moments in the story comes after the girls send Dugglesby a fan letter in verse (“We never met a murderer before”) and ask for tickets to his execution. In the final lines, Clandestine reveals that the “Happy Appendectomy” verse—which had so fascinated Dugglesby and led him to research Milly—was actually hers, not Milly’s. She ends by saying, “You come with me, Dugs, you have your girls mixed . . . Milly couldn’t write an iamb to save her life.”

By now, it should be clear that “Milly” uses a reversed mystery structure to mock misplaced logic in a world where illogical things happen because people themselves are illogical—something anthropologist Dugglesby Dunham seems to have overlooked in his studies. When he is found innocent, it is not because his reasoning succeeds, but because he gets caught up in the irrational social systems around him. A mix of mistaken perceptions and Dug’s new dislike of peanuts ends up solving the crime. Mostly unread, yellowed, and boxed up in Tulsa, “Milly” is another Lafferty story that deserves to be printed.