"Enfant Terribles" (1959/1971)

- Jon Nelson

- Dec 17, 2025

- 6 min read

“All of you children go into the dollhouse, and stay there for the present,” said Captain Keil. “I don't want you running around.” “I explained once that it was a clubhouse,” said Carnadine, her jaw grim . . .

So first, the facts. We end with metaphors.

“Enfant Terribles” (originally "Blood Off a Knife") is an early Lafferty mystery, written in 1959 but not published until 1971, when it appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Two years after finishing it, Lafferty wrote “The Transcendent Tigers,” one of his best-known and most loved stories. It was published in 1964. Both stories feature the unforgettable Carnadine Thompson, one of Lafferty’s most brilliant parthens. While both stories depict Carnadine as fierce, precocious, and authoritative (through investigation in the first and cosmic power in the second), she differs in her moral role, acting as a force for justice in "Enfant Terribles" but as a globally destructive scourge in “The Transcendent Tigers.” This is Lafferty being Lafferty, always pushing towards apocalypse.

"Enfant Terribles" begins with nine-year-old Carnadine, who is “going on ten,” asking beat cop Mossback McCarty, “Do you know a good way to get blood off a knife?” In “The Transcendent Tigers,” she will be seven, so there is a timeline hiccup. The setting is a vacant lot housing the clubhouse of the Bengal Tigers, Carnadine’s gang. Mossback, a recurring early Lafferty character, immediately becomes curious and asks to see the bloody knife. Eventually, he is led by an oblivious Eustace to a ravine where a “shabby dead man lay,” with the knife “prominent in the middle of his chest.” Eustace says that he “put it back where I found it like I said I would.”

Once the murder case is established, Captain Keil takes over to command of the scene and manage the actors. He berates Mossback as the stupidest patrolman on the force for letting a boy interfere with the evidence. The neighbors are summoned, including Fred Frost, an absent-minded inventor whose noise-eliminator work would have effectively drowned out any other sound in the neighborhood, and the terrible-tempered Tyburn Thompson. The victim, wearing a “prison kitchen knife” and a suit “issued to a man leaving prison,” is identified as one Charles Coke, a blackmailer who served five years and was recently released.

The investigation takes a turn when Captain Gold observes that the case is “almost too clear,” Judge Schermerhorn, a neighbor, confessing that he was the victim’s sentencing judge. The judge submits a typed confession, claiming that Coke tracked him down and, during a midnight struggle in the ravine, “slipped there in the dampness,” dying accidentally on the knife. The police readily declare the matter “a clear-cut case of self-defense” and prepare for a commendation.

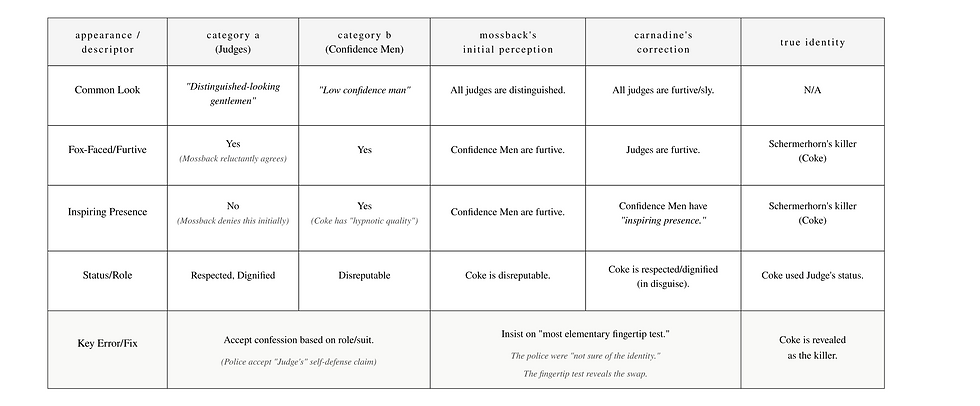

Carnadine sees through all of this. She challenges Mossback’s complacency, citing her obligation as “First Stripe” of the Bengal Tigers. Pressed by her insistence, Mossback is forced to admit that judges and confidence men often share the same disreputable appearances. Acting on her demand for a “most elementary fingerprint test,” the police return to the scene and discover the truth. Their prisoner is not the judge at all, but Coke, who murdered Schermerhorn, exchanged identities, and planned to use a claim of self-defense to establish a new, respectable life. Mossback receives a promotion, and the story closes with a neat callback to Lafferty’s playful handling of the children’s ages.

This is straightforward, prenucleation Lafferty. I have been thinking about East of Laughter (1988) quite a bit lately, and what stands out to me now about “Enfant Terribles” is that, from the beginning, Lafferty’s murder mysteries are never really about murder alone. They are always metaphors, which is to say vehicles for his larger concerns. In the extraordinarily complex East of Laughter, he pushes this murder-as-metaphor-vehicle principle to its furthest extent in the canon, using it to make an incredibly baroque argument about identity and human institutions. Here, in 1959, at the very start of his career, he already thinks of the detective story as a medium for doing social meditation and critique, likely with Chesterton in mind. In EOL, the workd itself will become the guilty vicarage. While Carnadine is no Father Brown, the argument she advances about the appearances of judges and confidence men could easily have come from him. It is Chesteron pastiche.

The classical detective story restores order. That is a truism. Along the way, it also levels its criticism at society, using crime as its equivalent for the interrogation manners that obsessed 19th-century writers. Lafferty’s critique in “Enfant Terribles” targets the instability of public identity and the failure of institutional epistemology while poking fun at mores. The towering irony is obvious. Captain Keil and Captain Gold consistently privilege convenience and narrative coherence over evidence. They are eager to accept the killer’s elaborate, typed confession as truth. Dressed in the judge’s clothes, Coke is granted absolution. That the case appears “clear enough” is all that matters. The police’s reliance on the prestige of the confessor, a trusted “judge,” reveals an epistemological laziness that would make Inspector Lestrade and Inspector Japp look like paragons of rigor. Forgoing a fingerprint test is Lafferty’s way of saying that institutional knowledge systems often exist to secure tidy resolutions rather than to serve truth.

This is where identity enters the argument. In the story, adult identity is contingent on appearance and social cues, in contrast to the children’s relation to fact. The children have fantasies, but as Mossback learns, literalism is the key to understanding them. We might call it the higher literalism of metaphor. Because the judge's corpse is staged to look like that of a dead hobo, he becomes one in every sense that matters to the authorities. Conversely, Coke is an incompetent murderer and a fool who repeatedly undermines himself, yet no one except Carnadine is willing to name the hokum for what it is. For the adults, Coke is respectable because he looks respectable. Carnadine alone upholds the world of fact.

When truth gets pushed aside, Carnadine, fierce in her adherence to evidence, makes sure that the social narrative is accountable to the messy, inconvenient world of fact. In “Enfant Terribles,” there is a world of vivid (life-granting) metaphor. It is the world of the clubhouse and the Bengal Tigers. From within that world, Carnadine can mobilize facts and deconstruct the thinness of the neighborhood.

Here, a point about Lafferty’s development as a writer. It can be understood as a long complication of the relation between the “World of Fact” and the “World of Metaphor,” terms he used later. Early on, there is a rationalizing line in his work that appears in early plots, evident in texts such as Loup Garou. It shows up in the earliest sf he wrote. It is demystifying. When he later rewrote Loup Garou, he also reworked this rationalizing element, having grown very critical of the ease with which the world at large speaks for the world of fact. In East of Laughter, he puts the point this way:

It was once said that with the coming of the World of Computers, the World of Mythology would disappear completely and the World of Fact would have arrived. Was ever any notion more mistaken? The clear fact is that the World of Computers is entirely a world of Metaphor and Mythology. That is the whole purpose of it. We already had the World of Fact. Oh, the poor, dingy, hopeless, small-minded World of Fact! It didn’t deserve much, but it deserved at least to have its nakedness clothed with metaphor and mythology. The World of Computers is bearable. The old World of Fact was ceasing to be.

In “Enfant Terrible,” the outermost world—the world of the neighborhood and the police—is a world of sloppy, lazy metaphor, one in which it is easy to stage a performance of respectability. Shallow social metaphor predominates. Everyone is a social actor. Lafferty exploits the staginess of the classic detective scene in which the suspects are brought together for scrutiny. Line ‘em all up, boys. I call them actors, but it is also a detective playing with his dolls.

“Get them all here right now, men, wives, children and domestics; and let nobody else near. We will talk to them right here. It is a shaddy nook here by the dollhouse.”

Beneath this world lies another world of metaphor: the world of the clubhouse, the children’s world, which does not paper over the violence of the outer one. I have written about this elsewhere in terms of Lafferty’s recurrent use of caves. In the Carnadine sequence, this counterworld is red in tooth and claw. It is tigerish.

Where, then, do we locate the World of Fact? Is it closer to the clubhouse, this second world of metaphor, than to the neighborhood, the first? After all, both are worlds of metaphor. That some metaphors are far better than others seems to be Lafferty’s point. Some metaphors capture how things really are. As East of Laughter puts it, when its characters abandon their quest for the World of Fact:

Even the Quest for Reality of the talented but diminishing Group of Twelve has now changed (without their knowing it) into the Quest for Acceptable World Metaphor.