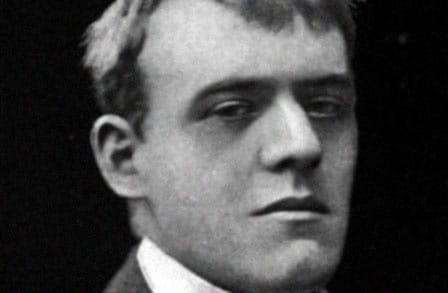

Ib. Belloc

- Jon Nelson

- Aug 11, 2025

- 17 min read

Updated: Nov 22, 2025

R. A. Lafferty unequivocally, categorically denied the Jewish Holocaust. This is sad, and inevitably complicates any discussion of his work, though the fact itself is not complicated. I used to be annoyed by Robert Silverberg’s comment that people knew there was great sadness in R.A.L. It was patronizing, and it didn’t make sense, but it is coming into focus for me. The Holocaust materials should be documented in the Tulsa archive in the McFarlin Special Collections for the benefit of future researchers because some people will not want to see them or hear about them. They will not think through what they mean for Lafferty and conspiratorial ideation. Amid the thousands of items, red circles should be drawn around them because they are items that are worth discussing and thinking about.

People will differ on why Lafferty embraced Holocaust denial. Was it rooted in his provincial upbringing, his Catholic faith, his instinct for contrarianism, his library? What, exactly, was in the mixture when it came together and lodged in him? Why did he persist in something so pointlessly foolish? Whatever the cause, it will cast a shadow over his legacy. It will also achieve something he wanted: it will link him to Hilaire Belloc and G. K. Chesterton—two brilliant Roman Catholics, one cradle-born and one convert, whose reputations, too, are marred by very different shades of antisemitism and who find little welcome in the academy, although if you are Chesterton, it has helped a lot to have fans like Borges.

But the Belloc connection may prove to be more interesting than the Chesterton one. Lafferty had Chesterton’s lightness and depth but Belloc’s saturnine suspicions and humorlessness about many issues where more Chestertonian wisdom would have done him good. He said he was far happier than most people he knew, but he was liable to being unhappy about other people. That makes him as unlike Chesterton as it gets. One of Lafferty’s favorite words was scorchy. It’s funny like Chesterton, dangerous like Belloc.

I predict two main ways of dealing with the now public problem of antisemitism in Lafferty:

Approach 1) Secular Quarantine A strategically secular reading says Lafferty’s views soured over time: late positions diverge sharply from the earlier self. It posits a break between the Catholic-intellectual strain of “traditional” antisemitism and the virulence of Holocaust Revisionism, emphasizing: (a) no antisemitic content in early correspondence; (b) the year he repeatedly gave as when he stopped writing; (c) the fact that his most troubling statements appear only after that date. By downplaying continuity, this approach lets the “never did accept” the Six Million line that Lafferty wrote in the Holocaust-denying letter to Dan Knight be absorbed gradually. Nasty Lafferty is Late Lafferty. Quarantine the problem for Lafferty Studies.

Approach 2) Theological/Continuity Integration A confessional reading rejects the rupture thesis and asserts continuity: the late statements extend long-standing commitments rather than contradict them. It situates Lafferty’s remarks within Catholic traditionalism—supersessionist motifs if not full supersessionism, anti-modern polemic, typological portrayals of Jews—reads irony and satire as technique rather than disavowal, and treats scattered early cues as seeds that later surface. On this view, Lafferty’s absolute Holocaust denial—preceding his embrace of IHR-style revisionism—expresses a historical skepticism consistent with his later IHR phase. The upshot is to absorb the offense into the unity of the oeuvre and the religion: Lafferty is Always Lafferty: Holocaust denial persists; only the intensity shifts. This sees the REALLY BIG critical problem as Holocaust denial itself, because that is what shapes something like the absence of the Holocaust in his literary work—not the revisionist IHR talk Lafferty learned to articulate from the late 1960s to the 1990s, which is a biographical issue relevant primarily to understanding how he came to express his ideas about Jews in personal letters. Reject quarantine and integrate the problem for Lafferty Studies.

This is an aerial view of possible paths forward, a preliminary attempt at an intellectual forecast. It is admittedly rough, but it outlines the two most plausible interpretive models I expect to emerge. In time, there will be more concrete details, along with nuances in how one might subscribe to either.

But I will say this: the first family offers a sanitized portrayal of Lafferty. It emphasizes a narrative of personal intensification while erasing what we might call Deep Lafferty—the peculiar conspiratorial constellation of quirks that produced the novels of the late sixties. In doing so, it offloads the hardest challenges for the Lafferty critic. The result will be engineered to manage his reputation in ways that feel superficially convincing, and therefore may well gain traction in some quarters, but it will not be wrought to last. It is, of course, the easier path: load up on footnotes and bibliography so that readers don’t hear, echoing in the background, Lafferty’s own words that he “never accepted” the Jewish Holocaust. The scholarly apparatus is indeed necessary, but footnote number one should be that Lafferty himself said he “never accepted” the Jewish Holocaust. It is his entry on one of two conspiracies that he thought defined the post-War era: the propaganda of international Jewry, the other being Modernism within the Church.

The second approach is mine: after reviewing his Tulsa correspondence and other sources, it is more persuasive to me—though more immediately damaging to Lafferty’s reputation, perhaps. His early views and blindspots predisposed him to embrace the arguments of denialist literature, this because of a position he always held. Lafferty became more culturally disaffected over time, but he does not fundamentally transform. He was a Holocaust denier and a crackpot on this one from the jump. In the first, more “rupture”-oriented model, change outweighs continuity. In the second, continuity outweighs rupture.

The crux is "intensification" in Lafferty. Does he take a markedly darker turn, or is he essentially the same man, someone who never accepted the historical reality of the Jewish Holocaust but later became interested in IHR materials because they reinforced a preexisting conviction that the Six Million was false? That looks like an honest take on it to me. It is also what he wrote. In this second view, the post-1982 Lafferty becomes aware of, and supportive of, the IHR program, primarily because its arguments suited a belief he had long held: the Jewish Holocaust always was, in his mind, a historical fabrication and ideological conspiracy against Christendom. This leads him to root against Christians such as the famously evangelical Protestant Hal Lindsey. Otherwise, Lafferty is pretty much the same guy, writing the same kind of fun and quirky letters he liked to write when he wasn’t being transactional. Have fun was his sign off.

Lafferty sometimes cited Belloc’s test for good writing, that the hardest thing in the world to describe is a knot or a tackle. Belloc set Lafferty’s benchmark for writing, and Lafferty left his readers with a knot. Those readers will need to think about how deeply Belloc tied it around him with his consent. That’s unlikely to happen. The reason is simple. Belloc isn’t much read or much understood, and Lafferty is a cult writer with an aging fan base. Chesterton is familiar. Chesterton is more than a name. Belloc is a name for people, one they heard about when reading something light on C. S. Lewis.

Both Chesterton and Belloc wrote prodigiously, yet I would wager that few really bookish Catholics now have a picture of what all Belloc wrote. That is to say his audience does not know him. It does not know how much history was in Belloc’s project or that history was its dead center. They weren’t raised on his children’s poems, and they didn’t sit down with him for their first big history lessons a few years later. Belloc got intellectually demoted by almost all Catholics after Vatican II. This is about the Jew, as Belloc might have said, but it is also that Belloc will not hold a modern reader’s intellect for long unless one shares his unyielding Catholic social vision. Too much of him belongs to Old Europe, the thing Lafferty thinks we are amnesiac about. That quality makes Belloc worth reading at times because he is so out of step with the mid-century he died in. Belloc is a fine writer, a prose writer of genius in fact, a point almost all his peers acknowledged, but Belloc is far too much for the casual Catholic mind, too little for the contemporary one. He was the Christopher Hitchens of his time but on the other side. For Lafferty, he was a living figure, dying in Lafferty’s early middle age. Ironically, Belloc is making a reappearance among Catholic Rad Trads who are under thirty. Nick Fuentes would be a fan. And, frankly, the disastrous political climate is more favorable to Holocaust denial than it has been since the Allies liberated Auschwitz.

So the Belloc-Lafferty connection deserves close study now that we know about Lafferty’s January 24, 1990 letter and how it directly connects to his Holocaust denial and history being Lafferty’s hobby. But how?

One way might be to go back to Belloc’s attack of H. G. Wells’s Outline Of History throughout the 1920s, thinking hard about how anthropology was a central issue and seeing a bit more in all the mysterious Neanderthal stuff in Lafferty, and then looking a bit at other strange connections that crop up on the edges of Belloc’s entire social history of mankind. This becomes clear with the Holocaust denial information and what it says about Lafferty’s approach to historical information and the Catholic historical imagination.

I once thought it important, so I put some sketchy notes on it in my Sindbad: The 13th Voyage document as a reminder. I now think it necessary. Not only did Belloc give Lafferty his writing test, he gave Lafferty a view of history that runs through many of Lafferty’s novels and stories. In Sindbad this is meta-historiography: the Catholic Church blew it after defeating Arianism. It got lazy. It allowed the heresy of Islam to become a “religion.” For Belloc and Lafferty, this is linguistic error. There is only one religion, and the rest is a foolish, if well-intentioned, ecumenical lie. History will reveal this to you, if you can fortify yourself against historical amnesia. This is Belloc’s master thought, and it is a typical Lafferty plot. For instance, some of it can found in The Fall of Rome where Belloc appears early as an authority on history. The Belloc on Arianism in the Fall of Rome is what might be called "Good Belloc." Sindbad, “Bad Belloc.” Frankly, I am in agreement with some of this, but I think the Holocaust denial was pathological. I doubt Belloc would have been a Holocaust denier because it fit his model of the tragic Jew to a T, though Belloc would have enraged sensibilies by what he concluded: I told you so.

In the long run, Belloc will be seen as being just as corrosive and influential on Lafferty’s legacy as he has been on Chesterton’s. And just as Chesterton cannot be understood apart from his friend Belloc, neither can Lafferty. Belloc was annealing and hardening for both men. It is tempting to imagine a kind of literary subtraction, as if we could remove the “Bad Belloc” and keep the rest. But it was the Bad Belloc—the one with his conditions of possibility and his religious paranoia—who gave Lafferty tools to build his own extraordinary worlds, ripping apart the pages of history like an enraged Snuffles. We cannot pull the Belloc DNA out of Atrox Fabulinus and still have Atrox. We cannot strip Belloc’s fears about Freemasonry and other imagined forces from the mind that produced Fourth Mansions. In The Three Armageddons of Enniscsorthy Sweeny, Chesterton’s “Nightmare,” which takes place in fog and shadow, becomes Belloc’s fiery nightmare of historical power scheming against the Church. Here, the smaller Belloc—smaller but in many ways more intellectually powerful—is no longer hidden behind Chesterton’s hulking but genial frame.

Need for serious thought about the biographical relevance and historical outlook

The fact of Lafferty's Holocaust denial is biographically relevant to understanding both his life and his art, as is the fact that he accepted and repeated elements of older, culturally entrenched antisemitic tropes that came from Catholic, anti-Dreyfusard, and contrarian positions, while showing no signs of personal hostility toward Jewish individuals in his direct dealings. Holocaust denial will never not be a factor in Lafferty studies, because in his January 24, 1990 letter, he stated plainly that his hobby was history. He wanted to make readers think about history, but on his own terms, framed within his moral and religious belief set. As a coreligionist, I have to recognize this. One cannot read Lafferty and be remotely intellectual without seeing it and talking about it or passing by it in silence.

Nature of his antisemitism

His antisemitism was intellectual and historical in nature, rooted in traditionalist interpretations of Western history, a religious team thinking, and admiration for figures such as Belloc—whose own “virtuous antisemitism” he did not repudiate but subscribed to 100%. He could be deliberately provocative, maintaining that prejudice, in the sense of pre-judgment, was an essential component of thought. He remarked on the risk of appearing antisemitic when making controversial but truthful claims. These were not careless Lafferty lapses, but expressions consistent with a considered—if outdated and rationally unwarranted—intellectual stance. The best case study I can imagine on this would compile everything he ever said about Harlan Ellison. The evidence is mixed. Such a study would provide a precise picture of Lafferty’s antisemitism, showing what it amounted to on both a personal and professional level. Someone should write a paper.

Lafferty believed Jews were more prone to certain forms of atheism and harbored dual loyalty, and he denied the reality of the Holocaust, a view that frames the full extent of his antisemitism and that also appeared coded in his fiction. His stance lacked the interpersonal malice or bigotry toward individuals that marks more virulent forms, yet it was not subtle or sophisticated and was expressed through dated, ideological, and contrarian tropes.

Closing disclaimer and willingness to modify views

I may have overlooked relevant material in the Tulsa archive, and there may well be additional evidence in other sources, but this remains my current assessment of the worst that can be said about Lafferty’s thought, work, and character. He was a genius and an autodidact. Until further information is available and a serious academic discussion develops, these are the terms on which I understand this side of him. Given the near-total absence of commentary on the subject and the inadequacy of the existing scholarly frameworks erected around him, it’s a start.

---

Bryan Cheyette’s Construction of “The Jew” in English Literature (Cambridge University Press, 1993) remains is a useful work for understanding the differences between Belloc and Chesterton. What follows is an outline of Chapter 5:

I. Introduction: The Contradictions of Hilaire Belloc and G. K. Chesterton

Framing Quotations:

A. Hilaire Belloc, Europe and the Faith: Asserts there is no “Catholic ‘aspect’ of European history” because a Catholic sees Europe from within, unlike Protestants or Jews who look on it from without.

B. G. K. Chesterton, The New Jerusalem: Rebrands the accusation of “Anti-Semitism” as a more rational “Zionism” or “Semitism,” which he defines as the desire “to give Jews the dignity and status of a separate nation.”

Shared Ideological Ground:

A. Both authors are said to “accentuate many of the contradictions and ambivalences within Edwardian liberalism.”

B. Both are described as radical Catholic authors.

C. Their “maverick ‘distributist’ philosophy” rejected both Tory Anglican capitalism and secular socialism.

Hilaire Belloc’s Personal Contradictions:

A. An Anglo-French Liberal Member of Parliament.

B. Believed simultaneously in the redistribution of wealth and a return to a “homogeneous medieval Christendom.

C. Was a supporter of the French Revolution, yet was also one of the few public figures in England convinced of Dreyfus’s guilt.

Belloc’s Political and Literary Project:

A. His politics combined radical and reactionary elements, using an “anti-capitalist racial discourse” during the Boer War.

B. His novels constructed “‘Jewish’ financial scandals in Britain and France.”

C. His work foregrounded the “cosmopolitan Jewish financier” as an “alien, unassimilable force.”

D. Novels such as The Eye-Witness and The New Witness constructed the “Marconi Scandal” (1912-14) as the end of British parliamentary democracy due to the financial improprieties of “‘Jewish’ Liberal Cabinet Ministers.”

E. His fiction attempted to “balance” a violent “antisemitic” response with a “more rational explanation of ‘the facts’.”

G. K. Chesterton’s Distinct Path:

A. Unlike Belloc, he belonged to an “indigenous Arnoldian liberal tradition.”

B. His early work used cultural terms like “Hebraism and Hellenism.”

C. He gradually accepted an “insuperable opposition between ‘Jew and Christian’, ‘East and West’ and ‘Aryan and Semite.'”

D. This opposition became a tool for defining the “small uniform ‘English nation.'”

E. He viewed the “Marconi Scandal” as a turning point that “threatened the God-given identity of the English patria.”

F. His work constructed the “assimilated or ‘cosmopolitan Jew’” as a form of “‘heretical’ spiritual confusion.”

G. Cheyette notes the “pernicious influence of Belloc on Chesterton’s use of an increasingly racialized discourse.”

II. Hilaire Belloc and the Rationality of ‘Race’

Early Writings and Political Doubleness:

A. In Essays in Liberalism by Six Oxford Men (1897), Belloc argued that free trade had “enormously increased the prosperity of England, but it has been accompanied by a flood of population not wholly beneficial.”

B. This “doubleness” of his politics—qualifying liberal principles with fears of foreign populations—was a lifelong characteristic.

C. Biographers have read him as both a British radical and an “exotic” French “antisemite.”

D. Cheyette emphasizes the “Janus-faced nature of his social criticism.”

Distributism and Historical Views:

A. Belloc’s “distributism” was a Catholic, anti-socialist, and anti-capitalist philosophy developed in the inter-war years

B. He called for the redistribution of land to a “yeoman class” to prevent the populace becoming “‘semi-servile… wage-earners’.”

C. He feared the old “large territorial [aristocratic] class” was being replaced by a “newly formed plutocracy.”

D. His reading of English history saw the Reformation as a “‘largely Judaic’ fall from Grace,” which led to a “‘Capitalist State’.”

E. He idealized the Middle Ages as a time when “human relationships had not been destroyed by the cash nexus.”

Personal Animosities and Influences:

A. Belloc was isolated at Oxford for his militant anti-Dreyfusard stance.

B. He was reportedly “incredulous that one of his closest [non-Jewish] friends should have been in love with a Jewess."

C. He initially refused to meet G. K. Chesterton because he was told Chesterton’s “handwriting was that of a Jew.”

D. During the Dreyfus affair, he joined Paul Déroulède’s Ligue des Patriotes, which opposed Dreyfus’s defenders.

E. He was an avid reader of Charles Maurras’s Action Française and Eduard Drumont’s La France juive.

The Boer War and the Discourse of Corruption:

A. Belloc began to strike a “native note” in England by railing against “money-power” during the Boer War (1900-2).

B. He associated the Dreyfus Affair with the Boer War, arguing the latter was “openly and undeniably provoked and promoted by Jewish interests in South Africa.”

C. This coincided with an indigenous British politics of “corruption,” which objected to an “‘unEnglish’ plutocracy.”

D. The radical J. A. Hobson, in The War in South Africa (1900), described the war as a “‘Jew-Imperialist design’” run by “international financiers, chiefly German in origin and Jewish in race.”

E. Belloc utilized this discourse to “Judaize the ‘international financiers’.”

F. This created a binary between the “‘English’ citizenry” and the “rootless, degenerate ‘Jew’.”

G. His poetry from this period reflects this theme:

a. “To the Balliol Men Still in Africa” (1910) laments the loss of his friends, blaming the war on the “‘dregs of men’.”

b. “Verses to a Lord…” (1910) satirically interchanges heroic English soldiers with Semitic “‘money-grubbers’” like Beit, Wernher, Eckstein, and Oppenheim.

Belloc’s Novels and the Character of Barnett:

A. His fiction reflected the “double movement” leading to the 1905 Aliens Act, which sought to both empower the lower classes and “‘segregate’ Jews.”

B. Emmanuel Burden: A Novel (1904):

a. The project was delayed after publishers in 1903 feared the manuscript was a “‘Jew-baiting’ book.”

b. This experience taught Belloc to champion his views using the “language of reason.”

c. The novel charts the rise of the “cosmopolitan financier,” Mr. I. Z. Barnett, whose exploitative worldliness flourishes due to the ineffectual Englishness of the titular character, Emmanuel Burden.

d. Burden is depicted as both the embodiment of England’s history and a “‘burden’” on its future; his passive parochialism allows aggressive outsiders to dominate.

e. Barnett, a “German Jew” of indeterminate origins, is linked to corrupt Imperialism through his scheme to find gold in the “M’Korio Delta.”

C. The Fanatical Intermediaries:

a. In Emmanuel Burden, Charles Abbott is Burden’s business partner, an “Anglo-Saxon” figure of “explosive radicalism.”

b. The narrator qualifies Abbott’s views as “wildly unjust” and born of a “mania of suspicion.” His irrationality is counter-productive, leading to Burden’s fatal breakdown and Barnett’s ultimate success.

c. In Mr Clutterbuck’s Election (1908), William Bailey has “gone mad upon the Hebrew race” and attempts to educate the naïve Mr. Clutterbuck about international capitalism and the “‘Peabody Yid’” (Barnett).

d. Bailey is presented as a “diseased” figure who drips with the “‘antisemitic virus’,” thereby defeating his own cause.

D. Later Novels:

a. In Pongo and the Bull (1910), Belloc dispenses with intermediaries and speaks directly of the threat posed by Barnett, now the Duke of Battersea.

b. Set in 1925, the novel portrays the British Prime Minister forced to ask the lisping Duke for a loan to finance Imperial needs in India.

c. The Duke’s alien “‘racial’” nature is articulated directly, as he does “‘not understand blood that is not his own’.”

The Marconi Scandal and Its Aftermath:

A. Cheyette argues that Belloc’s novels prefigured the discourse of the Marconi Scandal (1912-14), a financial scandal involving Liberal Cabinet Ministers.

B. Belloc’s journal, The Eye-Witness (launched June 1911), saw the scandal as “conclusive evidence of an ‘Anglo-Judaic plutocracy’ running Parliament.”

C. Belloc distanced himself from the “fanatical” antisemitism of contributors to The New Witness (the successor journal), such as F. Hugh O’Donnell.

D. He advocated for a supposedly “rational” solution: a return to the “medieval” notion of “‘privilege’ or ‘private law’,” a euphemism for requiring Jews to give up national citizenship and enroll in separate institutions.

E. The Jewish Chronicle is cited as having unintentionally mocked Belloc’s position by suggesting his prejudice derived from an “imperfect knowledge of the facts.”

F. By the late 1930s, Belloc’s views became more fantastic, linking “Jewish Communism” to the Spanish Civil War and arguing that the Nazi attack on Jews was not “thorough nor final.”

III. G. K. Chesterton: Towards the New Jerusalem

The Marconi Scandal as Personal Turning Point:

A. In his Autobiography (1936), Chesterton described the scandal as “one of the turning-points in the whole history of England and the world,” dividing history into “Pre-Marconi and Post-Marconi days.”

B. Critics often view his antisemitism as an “aberration” caused by the 1913 libel prosecution of his brother, Cecil, which led to Chesterton’s own breakdown in 1914.

Pre-Marconi Semitic Constructions:

A. Cheyette argues it is a mistake to situate Chesterton’s antisemitism only after the scandal.

B. The Ball and the Cross (serialized 1905-06) features a “Jew shopkeeper,” Henry Gordon, who is of a “much less admirable type” than a Fagin-like Jew because he has an assimilated, well-sounding name.

C. In a 1911 talk, Chesterton distinguished between “two kinds of Jews, rich and poor,” concluding that “the poor were nice and the rich were nasty.”

a. The “broad-minded Jew” was an offense, while the “narrow-minded Jew” was an “excellent fellow” for maintaining his distinctiveness.

The Fear of Lost Boundaries:

A. Chesterton’s worldview was based on a fear of losing a “‘sense of limits’,” stating, “all my life I have loved edges.”

B. The “broad-minded Jew,” in his attempt to assimilate, lacks any sense of “limitation” and thus causes “offense.”

C. This Chestertonian inflection distinguished his discourse from Belloc’s.

Nationalism, Anti-Imperialism, and Zionism:

A. In Heretics (1905), Chesterton attacked Rudyard Kipling’s Imperialism as a form of “cosmopolitanism.”

B. He defined nationality as a “spiritual product.”

C. He was an extreme pro-Boer, defending the right of the “small Boer nation” to protect its “little farming commonwealth.”

D. His “Zionism” was intended to give Jews a “‘narrow-minded’ dogma and sense of patriotism” to neutralize the “broad-minded Jew.”

E. He believed Zionism would allow Jews to develop their own territorial patriotism, which they currently lacked.

Fictional Portrayals of Semitic Confusion:

A. Manalive (1912): The character Moses Gould is a “small resilient Jew” whose “negro vitality” and “dark eyes” point to a “godless bestiality.” His “shameless rationality of another race” prevents him from achieving spiritual transfiguration. His cynical smile is described as the “tocsin for many a cruel riot.”

B. “The Queer Feet” from The Innocence of Father Brown (1911): The owner of the Vernon Hotel is a “Jew named Lever,” whose world of “‘good manners’” abolishes spiritual relations. By the story’s end, Lever reverts to his racial type, his skin turning from “genial copperbrown” to a “sickly yellow.”

The Dreyfus Affair and Shifting Views:

A. Chesterton initially reflected liberal horror at the persecution of Dreyfus, identifying with him as an individual victim.

B. His book on Robert Browning (1903) shows a confusion of racial and cultural terms, referring to Browning as an “intelligent Aryan” who was interested in the Jews.

C. By 1905, he had changed his position, writing of a “‘fog’ surrounding the Dreyfus Affair.”

D. “The Duel of Dr Hirsch” (Wisdom of Father Brown, 1914) is presented as the culmination of this reassessment.

a. The story concerns a French Jewish scientist, Dr. Paul Hirsch, accused of treason.b. Father Brown is morally confused, comparing it to the “puzzle” of the Dreyfus case, where both sides seemed sincere.

c. The resolution reveals Hirsch has doubled as his own accuser, a Judas-like figure betraying France for personal glory.

Post-Marconi Fiction and Inter-War Decline:

A. The Flying Inn (1914) presents a stark contrast between Lord Ivywood’s futuristic Nietzscheanism, which blurs the boundaries of ‘East’ and ‘West,’ and a bounded, traditional Englishness.

a. Ivywood is surrounded by Jews and Moslems, whom he conflates as “Semites.”

b. The German-Jewish financier Dr. Gluck has a “hook” nose and “unanswering almond eyes,” signifying a fixity of “race.”

B. The Man Who Knew Too Much (1922) shows a “literary decline,” with a parasitic dependence on the politics of Belloc’s fiction and the New Witness circle.

a. The stories feature all-powerful Jewish plutocrats like “‘nosey Zimmern [who] lent money to half the Cabinet’.”

C. A Short History of England (1917) reads medieval history from a post-Marconi perspective, arguing that Jews were both victims and powerful “instigators of ‘oppression’.”

D. Post-WWI, Chesterton’s writing elided earlier distinctions, creating conspiracies between poor Jewish communists and rich Jewish capitalists.

E. In a late story, “A Tall Story,” he presents Jewish assimilation as the main cause of antisemitism, a reversal of the positions of H. G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw.

IV. Conclusion

Both writers used a political vocabulary that was commonplace at the time.

Belloc drew on radical anti-capitalist and anti-imperial discourse, positioning himself as a balanced narrator mediating between the “fact” of Jewish plutocratic power and the excessive, fanatical response to it.

Chesterton initially used the ambivalent language of Matthew Arnold but increasingly constructed “‘the Jew’ as the opposite of both a familial Englishness and a homogeneous European Christendom.”

In theory, he divided Jews into “good” Zionists and “bad” indeterminate citizens, but in his fiction, this distinction was undermined by a prevalent racialized vocabulary.

He was concerned with the indeterminacy of Jews who could not racially assimilate into a higher spiritual world.