Millions of Lafferty Words, Intellectual Compression, and Teasing Incompletion

- Jon Nelson

- Dec 7, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Dec 12, 2025

“In conceiving a story or inaugurating a plot which involves threads weaving with threads, if the thread A, or viewpoint character, should figure with the thread B in an opening incident of numerical order n (with respect to the incidents in the conditions precedent) there must be invented a following incident n + 1 involving threads A and C; an incident n + 2 involving threads A and D; an incident n + 3 involving threads A and E; and so on up to perhaps at least n + 4 or n + 5; and furthermore n must cause n + 1; n + 1 must cause n + 2; n + 2 must cause n + 3, etc.”— Harry Stephen Keeler

"Throughout [Lafferty's] writing career, these various affects and effects were used by Lafferty to construct stories and novels that nestled within larger (but often untold) tales and universes, and were often to be understood as epigonal offshoots of those larger, earlier, linguistically more complex, mysteriously governed worlds. In the end, his corpus as a whole gave off a sense of teasing incompletion and of secrecy: almost as though it was only the entire story (to which his numerous unpublished manuscripts added almost mythic stature) that made sense, that commanded the rest." SFE

I have been thinking about that romantic yet demystifying passage by John Clute. Another John—John Carey, the Oxford don and book reviewer—once wrote that any fine book review must contain such a passage. Carey called it an acid drop. Without its presence, he argued, one has not read a good review. An acid drop does several things, but it always does one thing above all. It flatters the reader. The twentieth-century rhetorician Kenneth Burke called elements like the acid drop a necessity of good rhetorical form. For him, rhetorical form is the satisfaction of an expectation. Consciously or unconsciously, readers do expect the acid drop in a book review, even a glowing book review, because the acid drop is not a total solvent: it is a high moment of intellectual domination that brings the reader of the book’s review closer to the reviewer than to the author of the book being reviewed. Consubstantiation is with the reviewer, not with the reviewed

There is a downside. Consider the velvety SFE entry passage. Imagine I am new to Lafferty. I may feel smarter and more informed than I actually am for having read it. (I think something like has this galvanized, quite rightly, Gene Wolfe Inc. by Clute’s rhetorical brilliance in his SFE entry on Wolfe.) I might recognize my recent experience with The Devil is Dead, and then I find the grandeur of my own alienated thought returned to me. Incompletion and secrecy. Yes, just that. Perhaps what I took to be a spiral was a Fraser spiral illusion. Perhaps there is nothing but—and here is the acid in the drop—teasing incompletion.

In rhetorical terms, this teasing bit is nimbly enthymemic, an enthymeme being an argument that relies on what the reader quietly supplies. A key part is left undeveloped because the writer assumes the audience already accepts it—or will accept it.

We might lay out the the logic like this:

P1. When individual works appear to indicate larger, hidden structures, readers tend to assume those structures exist. (This is the unspoken premise the passage activates.)

P2. Lafferty’s stories and novels present themselves as shards, offshoots, epigonal fragments of larger, untold, more complex worlds. (True.)

P3. Therefore, there must be a single, unified “entire story” behind the works—a total architecture that commands and explains the fragments.

This is the chain of inference the passage encourages. And then Clute’s idea of teasing incompletion undercuts it. The totality dissolves. The imagined coherence turns out not to be a key to Lafferty’s corpus but an effect produced by the corpus. A larger, coherent form in Lafferty? Quite likely to be a mirage or a Fraser spiral. The really acidic moment might be Clute’s line that there is something implied to be more linguistically complex that what we see, as if Lafferty trades on what he does not earn fully. Please look at the Coscuin Companion and Argo Glossary on this blog to see the reality. The materials exist. Lafferty was not teasingly incomplete. The fact is the vagaries of the publishing business failed him.

In Carey’s acid-drop terms: if the enthymeme has been activated and then undercut, the reader has taken the drop. You know you have if you feel satisfied. Congratulations—you have just had the equivalent of a fine book review, one that gratifyingly substitutes for reading the actual book (the supposed larger form). A book review is a quicker and cheaper stand-in for the attentional investment required of the real thing. There isn’t enough time to read all the books, after all; that is why reviews exist. Many acid drops are medicinal, even when they are lies.

There is nothing wrong with this. I appreciate the acid splash in the book trade. Of making many books, there is no end; most deserve a good dip. In this case, Clute leaves open the possibility that Lafferty's secret door opens onto nothing more substantial than what has always already been visible. This is the unpublished work’s “mythic stature, as Clute puts it. Mythic here is not the good mythic; it is the other kind of mythic—the mystifyingly mythic.

So the SFE reader might think, what is beyond the teasing incompletion? Perhaps it would simply be more teasingly, more incomplete Lafferty. Perhaps Lafferty is best taken as a moving handrail that only seems to lead somewhere. Clute does not say any of this directly, because one never states the missing parts of an enthymeme—the rhetorician expects you supply to it. That is how an enthymeme works: trust yourself, says the rhetorician, after trusting me to show you the best seat in the house. To be fair, Clute clearly respects many of the short stories. His acid eats into the larger Lafferty’s project, which encompasses the novels.

Now here is the truth. Lafferty wrote millions of words, and he did so with the mind of an engineer. By his own account—and there is little reason to doubt him—he possessed something close to eidetic recall for written language. He compressed information. His mental audio was nearly lossless, and anyone who reads him will be struck, again and again, by how unerringly he could summon the exact word for whatever he described. Much of his pragmatic marker/oral style is meant to hide this finicky precisionism.

Among genre writers, the number of words he used only once is astonishing (see my post on the statistics for the published works)—never pretentious, always precise—and a clear sign that something in his stylistic machinery was fundamentally different. And then there is the matter of how thoroughly he hides writerly labor. This, strangely, is almost never remarked upon. Fun fact. Lafferty used more than nine hundred sources while writing The Fall of Rome, yet he took great care to conceal that scaffolding from the reader’s experience. The most anyone has said or apparently noticed is Darrell Schweitzer, who talks about one or two.

One of my aims for this blog is to confront the two types of problems that arise when reading Lafferty at scale. For most Lafferty readers, he is a short story writer, someone who turns out brilliant, self-contained performances. Part of his genius as a writer is that he was able to present himself this way, and he is thoroughly enjoyable if one wants to read him as science fiction’s master vaudevillian. At the same time, as I’m sure is clear if you read this blog, it is a bit of a put-on. The man was up to other things. When someone says he did not take himself seriously, it is true. When someone says that implies that he did not take his ideas seriously, it is bullshit, as reading his correspondence quickly reveals.

The problem for anyone wanting to get a grip on Lafferty is that he has two radically different strategies, and both create different sorts of reading pleasure. There is a modal gap between them. And both turn on the problem of informational density, which, paradoxically, contributes to the sense of teasing incompletion through compression. Sometimes what seems incomplete is being broadcast at 3700 angstroms. There is the centripetal Lafferty and the centrifugal Lafferty.

Over the last few months, I have decided that the best way to talk about a Lafferty short story is just to call it a story world. I thought about calling these story worlds cosmia or something similar because they have their wild logics and metaphysical rules, and part of Lafferty’s gambit when he writes a significant story is to make each cosmium both continuous and discontinuous with the others. On the continuous side, you have the ghost story at the macro, with its lines of filiation, overlapping themes, callback phrases, repeated character types, and reduplicative conceptual patterning. I needed new concepts to see this; hence, the concepts page.

On the other hand, there is the discontinuous side, where each story world has its own conceptual architecture, dense networks of allusion, etymological texture, anti-secrets, and unresolved puzzles, along with more than a little didactic axe-grinding. Each one burrows down with informational density. What ties the two sides together, the continuous and discontinuous, is, again, informational density. When most himself in his short fiction, Lafferty is an easy-going but camouflaged maximalist. That a brilliant maximalist is known for short stories that people call oral is not the least of his weirdness.

The writers I know best and enjoy most are maximalists. I believe the universal shows itself in the particular, so the more detail a literary artist can muster, the better. I am an essentialist, as are many contemporary thinkers, just not the ones who show up in roundtables about literature or all things sociological. To give but one example, Saul Kripke was one, so anyone who thinks essentialism is dead is philosophically illiterate. Essentialism is the reason why the writers I love most are Dante, Milton, Rabelais, Swift, Sterne, Blake, Joyce, Nabokov, and Pynchon. Lafferty is becoming one of those writers for me, but this is a middle-aged accident. On the deepest level what Clute sees as teasing incompletion is a symptom of not being attuned to how Lafferty orients the reader to Prime with his metaphysical games.

One of my heroes is Donald Ault, who understood parts of William Blake better than anyone. He was also one of the great champions of Carl Barks because he knew that the visionary contained both Duckburg and The Four Zoas. Ault was not trying to raise low art into high art because those were not categories that interested him. There are simply visionaries who demand architectonic treatment if they are to be taken in.

This goes, too, for some writers who are in many ways bad artists. Terrible artists but interesting ones. I wish someone would be architectonic about one of my favorite terrible writers, the mesmerizing Harry Stephen Keeler (1890–1967). As with Lafferty, there is something almost schizophrenic about Keeler, and one of the great books for reading visionary outsiders like Keeler or Lafferty is the mostly forgotten study of schizophrenic art by Hans Prinzhorn (1886–1933), Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922). Not that Keeler or Lafferty were themselves mentally ill; rather, both deployed phantasmatic artistic strategies to depict a culture already halfway to pathology.

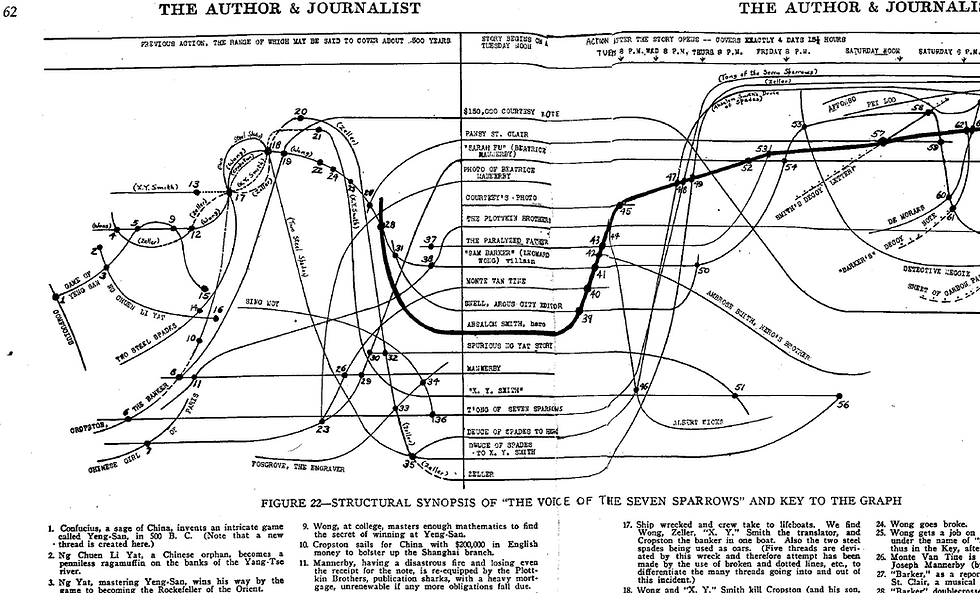

Keeping in mind how intricate Lafferty’s plots become in the 1970s novels, I want to linger with Keeler a moment longer. I defy anyone to summarize a Keeler plot adequately after one reading. Keeler created a method that made it nearly impossible. He called it webwork, his eccentric approach to plot construction: instead of treating narrative as a straightfoward linear chain of events—a “row of bricks”—he imagines it as a geometric structure woven from intersecting “threads.” These threads are characters, objects, and sometimes mere curiosities. In a webwork plot, an enormous cast becomes entangled in a scheme of staggering complexity and coincidence (think of Lafferty’s version of webwork in The Elliptical Grave or East of Laughter).

Keeler often drew elaborate diagrams to map these structures, in which every encounter exerts a kind of physical force that “deviates” a character’s trajectory, guaranteeing that no strand remains loose for long. Everything is gets pulled into a "mathematically" unified, if frequently absurdly contrived, resolution. As with Lafferty’s story worlds, Keller’s odd formal solution was a result of his lack of interest in exploring human interiority through the technology of the novel. He was a genre writer who did not fit.

Lafferty wants to gratify the human hunger for the Logos. Keeler’s technique was meant to gratify the human hunger for order by forcing the seeming chaos of modern, urbanized life into a perfectly logical, exhaustively interconnected design—a literary Rube Goldberg machine whose gratuitous intricacy is itself the point. It is, of course, a non-sacramental totality, this Keeler totality, yet it is a principled and baroque attempt to seize totality, and to sensitize the reader to it. In its immanent logic, it veers away from Lafferty, but it is not unrelated. The totalities Keeler’s webwork produces are neither accidental nor teasingly incomplete, and you will feel this if you are one of the few with the patience to read him. Following a Keeler novel demands tremendous concentration, though digital tools could make the task somewhat easier. Why? Because of the sheer informational density in Keeler. The problem is that no cares enough about Keeler to create tools.

One thing writers like Keeler and Lafferty have in common is that they are both visionary and architectonic. Lafferty has the oceanic; Keeler has half-mad webwork. Lafferty is peculiar in that he is as “outsider architectonic visionary” as Keeler, but Lafferty readers have not read him that way. It comes down to the contingencies of publication history, his developmental pattern, and his intense privacy, which was combined with his being deeply out of sync with his time and disaffected by its fashions, as most visionaries always are.

There are now new tools in the banner intended to help a reader (me) better hold on to Lafferty’s informational density and move quickly through it, which brings me to the point.

At the micro level, each Lafferty story is architectonic, dense, overbuilt.

At the macro level, story worlds are linked by patterns, motifs, and ghostly lines of connection.

The reader’s sense of a missing totality comes from:

(a) this genuine cross-text architecture,

plus (b) the fact that only part of the whole corpus is published / accessible,

plus (c) Lafferty’s own concealment of his scaffolding.

Clute’s “teasing incompletion” mislabels as mere tease what is actually real incompletion (only Prime is complete) imposed by material contingency plus genuine excess of design over publication.

For this reason, Lafferty is uniquely interesting in terms of where the digital humanities are now. In the past, one could not have expended the amount of energy necessary to get into place the critical apparatus to read Lafferty thoroughly because he is, in terms of reputation if not in terms of merit, critically negligible. In the past, I have written about George Steiner’s ideas of difficulty and why they are useful when one looks into the face of textual difficulty. What follows is how I now see the issue of Lafferty’s difficulty, along with the challenges and promises that he poses for dogged readers and his most thoughtful fans.

Contingent Difficulty: Reconstructing Lafferty’s Informational Density

Steiner’s contingent difficulty is really an idea that identifies works that require external knowledge the reader does not yet possess, and Lafferty scores high here. First, he is profoundly literate theologically in a tradition that most of his readers will not understand, then his fiction is saturated with etymological play, what I have called historical bricospolia, metaphysical argument, lost theological debates, Indigenous histories, displaced quotations, and private symbolic systems that are going to exceed any single reader’s grasp.

What once required decades of archival work can now be approached with AI-powered concordances, semantic search, and automated pattern detection. I use these tools in my thinking about Lafferty because I think they are here to stay and because Lafferty is an astonishing test case for them. The rise of these tools and the accident of having become interested in Lafferty at the same time has been an important learning experience for me.

These tools do not replace interpretation, which is what my blog posts do, but they do make it possible to assemble the distributed information needed to even begin reading Lafferty macroscopically. Digital humanities methods (vectorized text similarity, clustering, allusion detection) allow the reader to model the informational density that previously overwhelmed traditional close reading. This doesn’t demystify Lafferty. In a way, it restores the conditions of uptake, making apparent the contingent frameworks that his fiction assumes. Conceptual shortcuts, as it were.

Tactical Difficulty: Lafferty’s Deliberate Obliqueness and AI as a Pattern-Tracking Supplement.

Steiner’s third form of difficulty is tactical difficulty—difficulty by design—and it is everywhere in Lafferty. He doesn’t expect the reader to work, but he expects his ideal reader to be smart and to have worked. He obscures transitions, inverts causality, screws with conventions, and embeds metaphysical premises without explication. He rejects the conventional notion of the novelistic character by going back to the older concept of character as type, and then he treats the pre-modern type as being fractal, as if type were explosive and radiating outward.

This difficulty is, again, architectonic, forming the latticework of the Ghost Story. Traditional interpretation can easily describe local narrative tactics, but AI tools excel at detecting recurrent structural moves: the recurrence of PRIME-coded metaphysical cues, the circulation of symbolic numbers, the self-replicating narrative geometries, and the fractal reappearance of themes across short stories and long works.

One of the things that I don’t like about the way most people have blogged about Lafferty is that they have tended to say you can understand Lafferty by understanding this more easily understandable, more conventionalized, less difficult form. The fact that Lafferty’s tall tales are cosmia is probably the biggest exemplar of this problem. When someone says, Here is a tall tale, it’s usually a sign that the person is skirting the informational difficulty of the story world.

Ontological Difficulty: PRIME, Metaphysical Commitment, and the Limits of Computation.

This is deep Lafferty, and it is Steiner’s deepest form of difficulty—ontological difficulty. It happens when a text challenges the conditions of meaning themselves. Frankly, this is the center of Lafferty’s project. Someone like Petersen is right to recognize that the stakes are ontology, not science fiction. Lafferty’s clear-eyed view on what he took to be PRIME, the real world (whatever he got wrong about it), does determine the metaphysical substrate against which all post-novelistic fiction must answer.

It means that his writing scribbles at the boundary where narrative becomes metaphysical inquiry. Digital humanities tools can trace the distribution of metaphysical motifs and model cross-textual topographies, but they cannot resolve ontological commitments or adjudicate metaphysical truth. That is where people need to argue.

However, they can help us perceive how Lafferty sets up this difficulty: how historical mimēsis, Romance, metaphysical comedy, and fabulation all refract the problem of how contingent worlds relate to the World. And because the final difficulties are always ones of ontological commitment, the new tools of the digital humanities stop here, right where the ontology of the person begins.